Episode 110: Synthetic Armour and Smithing in France, with Anthony Rischard

Share

You can also support the show at Patreon.com/TheSwordGuy Patrons get access to the episode transcriptions as they are produced, the opportunity to suggest questions for upcoming guests, and even some outtakes from the interviews. Join us!

Anthony Rischard is a blacksmith, historical martial arts practitioner and proprietor of Black Armoury, one of the largest suppliers of historical martial arts gear in Europe. In our conversation we talk about how Anthony gave up his office job to become a full time blacksmith in France, and his move into starting Black Armoury. Have a listen to find out why they began producing suits of armour made entirely from synthetic materials and what the benefits of plastic are compared to steel. The last couple of years have been unusually challenging for Anthony's business, especially with the current supply issues across Europe and the situation in Ukraine.

There are a lot of photos to share with you!

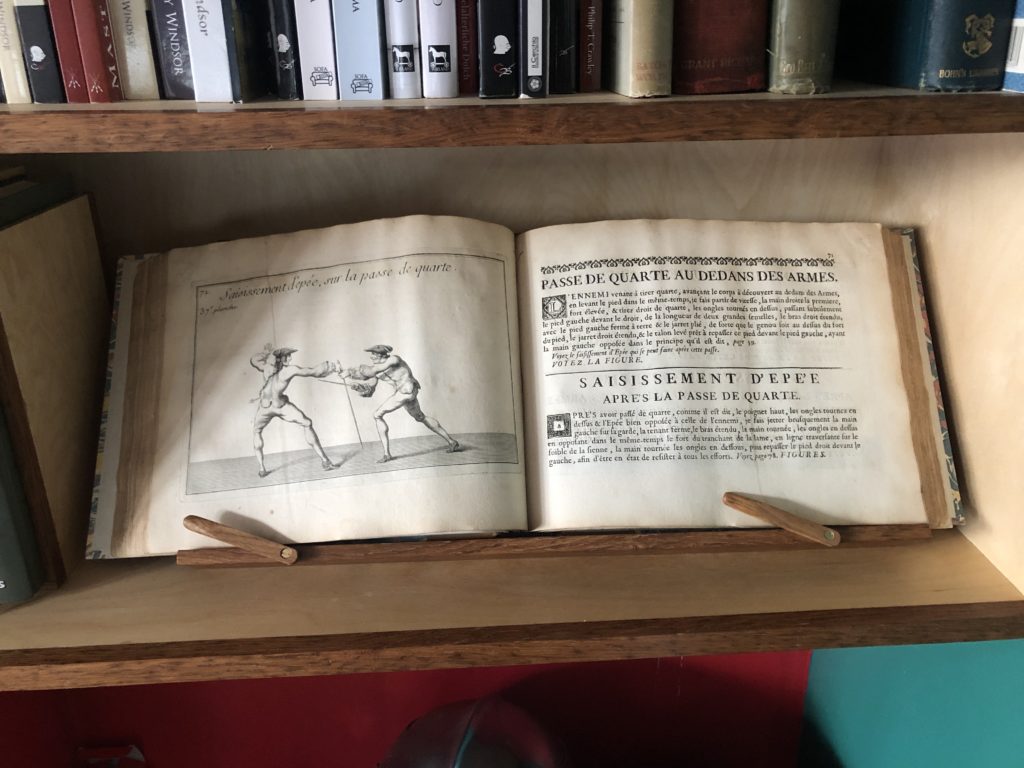

Firstly, here is Guy’s 1740 Girard:

Now, for the hot metal:

Château de Saint Saturnin

https://www.chateaudesaintsaturnin.com/en/history

https://www.chateaudesaintsaturnin.com/en/restauration

Door from Notre Dame de Mailhat (Lamongie France)

Before:

After:

Anthony’s favorite longsword:

Pavel Moc blade, rehlilted by Anthony. Fun fact: the grip covering is 1930’s lizard skin from the Chanel workshops, these were used for the backing of clamshell ladies pocket mirrors. A great advantage of working in restoration - people give you all sorts of weird and wonderful things.

Transcript

GW: I’m here today with Anthony Rischard, who is a blacksmith, historical martial arts practitioner and proprietor of Black Armoury, one of the largest suppliers of historical martial arts gear in Europe. So, Anthony, welcome to the show.

AR: Thank you, Guy. Good morning.

GW: So just to kick us off, I know where you are, but that's because we know each other. But for the sake of the listeners, whereabouts in the world are you?

AR: I am in South Central France, in the volcano country to the south of Clermont-Ferrand, in the central mountains of France.

GW: So sort of middle of nowhere.

AR: Sort of intentionally middle of nowhere. Well, middle of nowhere, that's kind of fun. Yes. I'm in a tiny little village, population just under 70.

GW: Wow. That is a tiny village.

AR: Which is fantastic. We've got lots of space and mountains and history and castles and stuff. But we're only 10 minutes away from a medium sized town for France, which is about 10,000, and we're only 40 minutes from the city. So in that regard, we're not as lost as it may seem. And when we moved here, my brother actually said, what are you doing in the middle of nowhere? And I told him, well, look, you know, the cool thing about where we are is that we're close to nothing, but we're far from nothing. We're 4 hours from Paris, we’re 4 hours from the Alps. We're 3 hours from the Mediterranean. We're 5 hours from the Atlantic. I mean, come on.

GW: Yeah. And by European or continental standards, that's actually pretty close. By British standards, 4 hours from anywhere is the other side of the world.

AR: Well, and by American standards, it's right next door. And as you can hear from my accent, I'm sort of in between the American and the French thing.

GW: Yeah. I mean, not your bio says you’re from Washington, D.C. originally.

AR: I was born in D.C. I'm an expat kid. I'm lucky enough to have two fathers. I have got my natural dad, David, who is from Texas, and I was raised by my second father, my stepfather who is from Luxembourg.

GW: Wow, that's quite a contrast.

AR: So my mother's French. I've got a Texan dad who was a lawyer in Washington, and I've got my Luxembourgish father who had his career at the World Bank in D.C.. So I was born and raised primarily in Washington, D.C., travelled a bit, went back to the States, travelled a bit more and ended up in France.

GW: Wow. So you actually chose France deliberately?

AR: I chose France deliberately.

GW: That is not to suggest that one shouldn't choose France, deliberately. It's just interesting to me because a lot of people just end up where they are. Whereas, people are often completely baffled that my wife and I deliberately chose Ipswich for various good reasons when we moved here in 2016. And literally, nobody we've ever come across in Britain has understood that choice because they didn't understand the various variables that we were weighing up. Yeah, we deliberately chose to move to this specific place. And you have clearly done the same thing, which is unusual.

AR: My wife and I have a number of variables. One of the variables of course, for being exactly where we are, is that this is the local area that my wife is originally from. When we came back from, from or when we decided to be in France, this was the natural place to land that initially it was potentially a temporary landing. And that was almost 14 years ago.

GW: Okay. Well, yeah. And, you know, I have plans to come visit because it sounds absolutely beautiful. I can see from the books behind you that even if it's a rainy day, there'll be plenty to do.

AR: Oh, there will be. Well. The books.

GW: Yeah. Okay. No, the listeners can’t see that, obviously. But, yeah, Anthony just got up and moved his laptop around and yeah, there is a pretty impressive library behind him. Michael Chidester will be pleased, there is a little special stack. I can identify them from their spines from here. The entire output of Michael Chidester’s bookshelf, fantastically high quality facsimiles. It's like they’re glued to the wall but I assume they can actually be removed.

AR: Absolutely. It's one of those fantastic little what they call invisible shelves. It’s got a little bracket that holds the bottom book and you just stack the other books on top of it.

GW: Very clever. Yeah, because it does look like they're just hovering against the wall.

AR: Yeah, it's really neat. You can find those online everywhere.

GW: Okay, so let's start with bashing hot metal, because it's fun, right? So you are a smith and I've seen some pretty fancy railings and steel furniture and stuff on your Facebook pages when I was doing research for this interview. So what kind of smithing do you do? How did you get into it?

AR: Well, I spent a number of years as a historical ironwork restoration smith. What that means is working with a lot of churches and castles and whatnot, doing restoration of their ironwork and some creation of ironwork in that context as well. Because obviously, a lot of historical ironwork has been lost through the centuries. So there is some recreation that needs to be done, some interpretation there as well.

GW: How did you get into that? I mean, most historical sort people when they think “smith”, they think somebody's bashing out swords. But what you're talking about is sort of architectural reconstructive.

AR: Absolutely. Metal and sharp things. And I know that you're in love with sharp things as well, beyond swords. Metal sharp things have been a passion for me since as far back as I can remember. And I've always, always played with metal. Not just iron, but just steel and silversmithing and copper work and bronze casting, through the years. And then smithing as a profession came later on. I only did that once we were back in France, so I was in my early forties. I'm 52 now, just for the record. So I always had other professions in the past, primarily marketing and advertising, online stuff.

GW: Going to work in an actual office with people wearing suits and computers and things like that.

AR: Yes. Scary stuff.

GW: Grown up stuff.

AR: The stuff of nightmares.

GW: I have no experience of that at all.

AR: But in parallel, I always had a small personal studio to do metal work.

GW: Sanity space.

AR: Exactly. Yeah. A refuge from the world to work with fire and metal and stuff. When we decided to come back to France and we talked about the middle of nowhere aspect of where we are. There were some decisions as well to be made as to what I was going to do for a living. And I decided to make a big change from that suits and computers worlds and develop the metal work as a business. I fairly quickly made the contacts that I needed to make to get into that professional world, polished up some training for the first year. A lot of my metal work was self-taught over the years, over 20, 25 years. But obviously on certain aspects of things, especially when you get into architecture, there are some certifications that are required to be allowed to do and whatnot. So I went out and got those.

GW: That's an interesting bit. Let's not skip over it. So you wanted to work on, I don't know, let's say some gothic cathedral or whatever, but you need to have a particular bit of paper so the people in charge of the building will actually let you touch their ironwork.

AR: Yes.

GW: So how does one go about getting that paper?

AR: And keeping in mind that France is France, which means that it's not just the person who owns the building, it's also the government and the official architects and the architects attached to the government and all that. How do you go about that? You get online and find out who is delivering the certifications and you select the one that is not just delivering a certification, but actually has something that you want to take from them as far as the approach and the technique and the background and the passion and all of that, you know, you're not just selecting a piece of paper. It's not just the diploma. It is also, in my case, anyway, I need to be developing a relationship with a human being or human beings. So I found that person, that school, about a three hour drive from here on down south of France, in Provence, and spent my weekdays there and my weekends here and got the certifications.

GW: How long did it take?

AR: A few months. I had sufficient background that we were able to gloss over the six months of basics that would have been required. And I guess you could say that it was equivalent of testing in to the basic skills and focussing on the missing skills and the missing knowledge. So it was fairly fast in that regard. And then it was a matter of getting the word out that I was here and qualified.

GW: Qualified and available.

AR: Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

GW: Huh. Okay. So what was the first thing you worked on as a professional in that regard?

AR: The first thing I worked on as a professional is about 40 metres from where I'm sitting right now. And if I lean out the window, I can see it. It was a small handrail for the little old lady on her front steps across from me in the village, who was no longer able to get up her steps.

GW: Without a handrail.

AR: And she was a lovely little lady who needed a handrail.

GW: And you had better do a good job because you're going to be looking at that thing for as long as you're living there.

AR: It is still there. And her daughter now lives in the house.

GW: Uses the handrail and it hasn’t fallen down.

AR: And then as far as historical monuments are concerned, the first few jobs were, because you're getting your feet wet and you're getting sort of vetted by the official architects on these things that you get some small work. And so, again, you know, a few handrails and a couple of gates and that type of thing. And then I fairly quickly got into a castle near here called the Château of Saint Saturnin, which is a very interesting place. It was the birthplace of Catherine de Medici's mother. A lady name by the name of Madeleine de La Tour d'Auvergne. And as such, it was a royal castle. Because when Catherine de Medici became Queen of France, she probably only visited the place once in her life, travel being what it was at the time. But she had a particular fondness for this castle, which was the birthplace of her mother, and financed it regularly, the upkeep.

GW: Handy to have a royal patron.

AR: Exactly it was a royal patronage. And the castle had a fantastic history during the Hundred Years War. And the South Tower was completely redone. The top of the tower was redone as an emblem of its action during the Hundred Years War. And all kinds of neat historical titbits. But one of the neat things about it is that we know from documentation that this castle had what was probably one of the first Renaissance gardens in France.

GW: Wow.

AR: Commissioned by Catherine de Medici, who was bringing this over from Italy. But the garden has not survived. Through the centuries the castle became a monastery and then it became a nunnery. And then

after the revolution it went into private hands. And so there was there are no plans and there is no record other than the existence of this Renaissance Garden and the location of the garden. So the current owner decided that he was going to commission the recreation of a renaissance inspired garden, because we don't have the plans for the castle and wanted all kinds of neat ironwork for the garden. So that was a two-year project. I can send you a few pictures of what we did.

GW: Yeah, please send us pictures. I was just thinking though, because I've talked to quite a lot of antiques restoration with furniture. And when you have an irreplaceable piece of furniture in front of you and you have to actually cut bits off it and stick bits on it and fiddle about with it. Generally, there is a very strong “I cannot afford to fuck this up” vibe. But what you're describing actually is much less stressful because it's not like there's this bit of iron attached to this ancient wall and you have to take it out put a new one in. So for a recreated renaissance garden. Actually making the ironwork for that feels to me from a maker’s standpoint as a very low stress introduction to actually working on these sorts of sites.

AR: Yes. I'll tell you about the project that you just described. It exists. But this one, yeah, no, absolutely. I mean, the stress came in when I realised the scope of what we had decided to do and the fact that I was working alone in my workshop with deadlines and oh my God, I'm never going to sleep again. And so there was that kind of stress. But of course, no, there was not the stress of screwing up something historical. That project was when I was subsequently given the restoration of the 13th century ironwork on the door of the of the church in Lamongie.

GW: That’s not stressful at all. Definitely send us pictures of that too. What did you have to do?

AR: Those doors spent a year in my workshop.

GW: And okay so you dismounted the doors and took them into the shop and dealt with them there.

AR: They dismounted the doors and delivered them to my workshop. I don't remember, but I had to, as safely as possible, remove 127 or something, medieval nails that were holding all of this together. Take everything apart. Clean off the 19th century paint that had been applied to all this. And reproduce the missing bits, because bits and pieces have been through the centuries ripped off, stolen, removed, a few pieces may have been sold on the antiquities market, whatever. And so restoring those pieces, cleaning the rest or documenting everything.

So these doors also required full documentation. There are some fantastic late romance animal heads, sculpted animal heads, for which I took moulds. There was there were some remnants of leather underneath the ironwork, because a lot of these church doors were covered in leather at the time.

GW: Really?

AR: So samples of that, I took samples of that, and I got them to the architects so that they could do some analysis on that. Unfortunately, I never got any results from him. So I don't know what they ended up doing with it. But anyway, that was gathered and given to them. I had to forge some keys which had been lost. Oh, fantastic story. You've certainly run across this as well in your furniture restoration. When you see old repairs that tell you some of the story of what you're working on.

GW: And sometimes it's like a love letter from a long-lost craftsman. Sometimes it's like hate mail from some recent pillock.

AR: Absolutely. And in this case, it's fantastic because this door had three locks on it. And the first lock was just the lock location that was visible on the door. The second one was broken and still locked.

GW: Okay.

AR: And it is perfectly visible and readable on the ironwork that one of the branches of the ironwork was bent aside to make room for the third lock, for which the key has been had been lost. So I had to forge keys for the third lock and repair the lock in order for it to function again. But the second lock, which from its style was probably a late 13th early 14th century lock was broken, and you can invent all kinds of fantastic stories around this. It is the morning of the wedding and the priest shows up and says, oh, my God, I've lost the keys. Or a baptism. Quick get the village blacksmith and break me this lock so that I can get into the church and perform the ceremony. Fantastic, fantastic things. But that was a stressful restoration of, okay, I've got to do this correctly. From removing the first nail and documenting everything all the way to getting the work done, installing the newly forged pieces. Now, that's interesting in itself, you've got to re-forge these things as identically to the originals as possible, while not muddying the waters for future research and future archaeologists. So all of the newly forged pieces are stamped on the back with their date of manufacture and my forge mark as well. And we made the decision with the architects to not weld these pieces to the original ironwork, but to mount them beside the pieces with a visible break between them.

GW: That’s a good way to do it.

AR: So that it was immediately readable that this is a restoration.

GW: Yes, a layperson wouldn't even notice. But anyone who knows they're looking at, okay, this door has been restored. There's a fine line between conservation and restoration. And it sounds like there's elements of restoration, like fixing the lock and getting it to work. And there's elements of conservation, like replacing the missing pieces, but making it clear that they are modern replacements, not original.

AR: Yeah, there's a third aspect as well, which is reproduction. I mean, there's conservation, restoration and reproduction - copies. That goes into the weaponry that we study as well. For me from an ethical perspective, it is vitally, vitally important that everything is readable, that you know this is a reproduction. That you know this has been restored.

GW: In honour of your Frenchness and in my display cabinet behind me. I’ll put a photo in the show notes. I have my copy of the 1740 edition of Girard. I got it as just unbound leaves that was missing the title page. Everything else is complete. So what I did is I had it re-bound by a professional binder who has done an absolutely glorious job of it. He's retired. Otherwise, I'd make sure to stick his name in the show notes. But he doesn't want any more work. I got my friend Jaakko Tahkokallio, who works at the University Library in Helsinki, which has a copy of the 1740. And he sent me scans of the missing page. And there is also in the 1736, the first edition. This is the second edition. So the title page is slightly different in the first edition. So he also sent me those pages. So what I've done is clearly different paper. Puts in the missing pages from this edition, which is the title page and the dedication to the king. Also put reproductions of the pages that are different from the 1736 bound into the back. And the note here saying where I got the book from, where these scans come from, so that anyone in the future who comes across this will know when it was bound and where those reproduced pages come from. So they can see exactly what's original and what has been replaced because it was missing.

AR: All of those steps are vital, especially the notes. I can't stress enough. And I'm saying this, I guess, for any collectors out there who acquire antique weapons, for example, or antique books. The importance of noting any intervention that you make on the piece is important because all of these things, with any luck, are going to outlive us by a long, long time. I mean, that's the intent. That's what collecting, whether it's a museum or a private collector in the end, is all about. I mean, of course, there's the joy of having custody of this thing for a while.

GW: You saw the grin on my face when I went to get my Girard, right? It’s a thing of glory.

AR: It's fantastic. It's fantastic. But in the end, it's not yours. It’s yours for the time being. It's yours for the duration of your ownership.

GW: Yeah.

AR: But it's also a responsibility and it's very important, I think, for all of us to remember that. I mean, I've got a few I mean, they're not they're not very valuable and they're not very old. But, you know, I've got a few antique originals myself and I realise this thing is going to be around longer than me. And when something is valuable and unique, valuable not just financially, but also as far as the history is concerned, the responsibility just grows.

GW: Oh yeah. I have a 1568 Marozzo, I've got a first edition Fabris and a first edition Capoferro. Once my wife and children are out of the burning house, they're next. I have questions. Okay. We were talking about getting medieval iron nails out of presumably like an 800 year old piece of oak. How do you do that without destroying the wood?

AR: You sacrifice the nail first.

GW: Okay.

AR: But in the end, it's not that difficult.

GW: I mean, you don't just take a claw hammer and stick it underneath and yank. That's not going to work.

AR: Well, for one thing, you can't. The way a medieval nail is installed. You need to think of it much more as a staple than as what we think of as a nail. Medieval nails were extra long. They were run completely through the wood and folded back on themselves.

GW: They were clenched.

AR: Exactly. They were clenched, which means that you can't just pull them out. So a medieval nail, as I was saying, was passed all the way through and bent over. And these things were designed to be removable. That's the other thing that we always forget in our modern world, where we don't have iron nails anymore. We have steel nails.

GW: As a restorer, you can order handmade iron nails. And they are woefully expensive, but they are the dog's bollocks for certain kinds of jobs.

AR: Yes, you can. And I've done it. But your hardware store nail is steel.

GW: A different beast altogether.

AR: Completely different thing. These are soft iron nails and unbending them is not a difficult thing. Now, when I say that, you sacrifice the nail, these are 800 year old nails, or close to it. Some of them will break when you're when you are unfolding them and need to be replaced.

GW: So you don’t forge weld them back together?

AR: No. Not worth it.

GW: Okay.

AR: Not worth it. From a restoration perspective, re-forging ten or 15 nails is a much better solution. And you give the handful of broken nails to the owners of the property, and they're all happy because they make little keychains for their nephews and nieces and their grandchildren.

GW: Yeah. And also nails back then were relatively expensive. Well, these days we think if you buy a big bag of nails for practically no money. But back then, nails being handmade and quite big and made of iron, they’re going to be, by our standards, relatively expensive.

AR: Well, by our standards, yes. I don't personally know of any research on the actual value of nails at the time, but at the same time, banging out nails was actually a lot faster than we would imagine. I was reading an article a few years ago by someone who had visited one of the last professional hand nail makers in Scandinavia back in the 1950s or 60s. And the rate at which this guy was churning out nails, it was just amazing. I don't remember off the top of my head, but he was he was churning out nails by the hundreds.

GW: We see this all the time. Like a modern woodworker, if they have a sawn plank and they are using their planes, which are set for dealing with finishing work and adjusting work on dried planks of wood, it's going to take them forever to get that piece of wood down to the necessary thickness. You start by putting a flat face on it, flip it over and get it down to thickness. If you're using like pre-industrial plane setups and wood that isn't fully dry yet, I've seen somebody take a six foot long board that’s about 18 inches wide and put a face on it. So one flat face, flip it over and plane about to say half an inch off it to get it down to thickness and he did the whole thing in about 15 minutes.

AR: Yeah.

GW: Right. It's unbelievably fast when they're using the right tools in the right way in the way that they used to be used.

AR: Absolutely.

GW: This reminds me of something. Something about sword fights. Use the right tool the way it used to be used, and suddenly it just works an awful lot better.

AR: Exactly. I mean, our modern concept of how things should be done is completely, completely skewed by mass production. And the fact that for generations now we've been used to things like, well, wood? How do you cut wood? Well, you saw it.

GW: No, no, no.

AR: The best way is you split it.

GW: And I mean, you do sawn planks, but they are expensive and hard to produce and they are weaker. And you only do it for very specific applications.

AR: Sawing is for when you need to cut across the grain.

GW: They did saw planks for like tabletops and whatnot, but like ships were made out of split timber because why the hell would you saw it? You saw it, you're cutting through the grain. You're not splitting it along the grain. So you don't have contiguous grain from one end to the other, so the board is weaker. In a ship, you don't want that.

AR: And then in smithing it's the same general idea. Punching a hole through steel is way faster than drilling it. And you're not losing any material.

GW: Right. When steel is expensive, that makes a difference.

AR: Exactly.

GW: All right. So we still haven't gotten that out of the piece of wood yet. You’ve unclenched it. What is next?

AR: Oh, you give it a couple of taps from the back.

GW: It just slides out.

AR: You just lift it out. Absolutely.

GW: Huh? So it doesn't get stuck to the wood in any way.

AR: It does not get stuck to the wood in any significant way. That's the other thing that we need to remember about the iron at the time. It does not rust the same way as modern steels will. Modern steels will tend to not only rust, but create oxides that increase in volume. And get it stuck in there. The way these nails tend to rust is that they will become more fragile. But the rust is kind of dusty and friable. So it tends to just fall right out and maybe you can reuse the nail, maybe you can’t. In this particular case and in a lot of cases where you have doors on churches, let's not forget the way people designed their architecture was so that they did not have a wet door.

GW: Because wet doors are expensive, you have to keep replacing them.

AR: And the wood is going to warp. And if you have leather on there, water is bad.

GW: Yes. Your door will normally be under some kind of a shelter. You see this in like medieval cottages that still exist throughout Suffolk. You don't have the front door on the outside wall unprotected. You always have some kind of shelter.

AR: Yeah, that's it. So the nails, you know, lost a few, have to re forge a few, but for the vast majority, they came out just fine. But that's one of the things about something that I just absolutely love is that a lot of the time you're making your own tools for the specific job. And so I did have to make three separate nail headers. That's the tool that forms the shape of the head of the nails. You do have flat nails like the ones that we know, but a lot of the nails are pyramid shaped at the top.

GW: So how do you make that?

AR: Well, the easiest way to make it is to take a sample nail. Put it through a plate so that it will hold straight up and bash a piece of hot steel on to the top of it to make a mould.

GW: That makes sense. And then so you heat up the new nail and you sort of bash it into the mould, and it just takes that shape.

AR: You preform it with the hammer. And to give it the final shape, you use the nail header.

GW: Okay. So you made three of those for this door.

AR: Because there were three different.

GW: Styles of nail.

AR: Well, clearly, they came out of three different workshops.

GW: Right. Okay. And each workshop would probably have its own particular way of doing it.

AR: And their own nail header. The other fantastic thing is ironwork, I say this a lot and because it's really how I feel about it, ironwork is, in the end, nothing more than a choreography frozen in time. You have all of the actions that went into creating a piece of ironwork. Unless they've been ground off or sanded off or whatever are still there and looking at the back of pieces that are meant to be seen will tell you so, so much. For example, I was able to recognise individual tools used on the back because they will leave their own mark. You're able to see where the blacksmith was working alone and where he had a striker hitting from the other side, because of the angles, because of the way it all works out. And in the end, you sort of have this almost cinematographic experience of seeing what was happening in the workshop when they were doing this. And that is just fantastic.

GW: You get the same thing when you open up an old piece of furniture. Not exactly the same. But like you can see, well, okay, these pine planks have been finished with a jack plane that finished on the other side. That puts it in a certain period. And looking at just the way things have been put together and the woods have been used and, you know, even things like the angles in which the dovetails have been cut for the drawers.

AR: Sure. And I'm sure like us, you might be able to see at some point as like oh, okay. Well, he stopped here because he was getting a little bit dull. He sharpened this tool and continued. It's fantastic stuff.

GW: Yeah. And it's like a conversation. Okay. I could keep blathering on about the architectural ironwork stuff for the rest of this interview. But I think some people listening might be expecting us to apply the same sort of approach and interest to swords. I mean, swords are nice. We like swords, don’t we?

AR: Let me jump right onto the question that you haven’t asked here. No, I do not make swords.

GW: I was deliberately not asking that question. Because it is too obvious. But I'm glad that you answered it. So why don't you make swords?

AR: I will make swords at some point when I have the time. Because swords are a very specific type of smithing that I have not practiced and do not have the time to practice. I do make blades, I do make knives and whatnot. But the long blade, the sword is not something that I have done. I have taken blades made by others and done cutlers work on them.

GW: Hilting them up.

AR: Making guards, hilting them up, making pommels, you know that type a thing. But bladesmithing the long blade is not something that I've done yet.

GW: It's a different thing. It's like making bows, right? When I first started making bows, the difference between making a piece of furniture where every piece of wood keeps its shape and doesn't move, and it's the shape of the pieces of wood to create the structure, versus a bow which has to store and release energy in a particular way. It is just completely different. And sword blades are the same. Like, making a hammer. Every smith makes their own hammers, because you would. But the sword blade, it has to resonate in a particular way. I think from a craft perspective, I think it's closer to bow making than it is closer to furniture making.

AR: I completely agree with that assessment. It’s its own thing. And it's not to say that it's more it's not more difficult. It’s just different. It's such a very, very different thing. And I've spoken to quite a few bladesmiths who would not do the heavy architectural work because they just don't have the experience, the time to learn it and whatnot. I do want to make some long blades at some point, but it will be later when I'm not needing to make a living with my time. It's a retirement kind of project more than anything else.

GW: Okay, so. I mean, there are swords on the wall behind you. Is that big long blade on the wall behind you a Del Tin?

AR: No, let me. No, this one is an older paddle lock blade. Re hilted by me. This is my personal longsword.

GW: Okay. For the sake of the show notes, would you mind sending us a picture of it? Because we've just been talking about it, and it's not fair on the listeners who can't see that. It's lovely. And it reminds me in a sort of aesthetic with some of the Del Tin longswords we were using back in the late nineties. So you do practice. How did you get into practicing historical martial arts?

AR: I got into practicing historical martial arts in several goes with long breaks. Due to various life events and travel and whatnot. My first discovery of historical martial arts as martial arts being practiced by people of our generation would have been in 1992 and 1993. In Washington. I was fencing epee, Olympic fencing in Washington at the time, and there were a couple of guys who would show up from time to time at the club with rapier and dagger and whatnot, would just do their thing off to the side.

GW: That’s early days. That's when I was starting in Edinburgh.

AR: That was very, very early days.

GW: Do you remember who they were?

AR: I do not. I played with them a couple of times, but I didn't really get into it. I was still interested enough in progressing with the Olympic epee at the time that I didn't make that foray immediately. But I guess it goes with my personality and I know this about myself is, I tend to be the kind of person that when I get interested in something, I go all in and tend to make a change, tend to stop what I was doing. And this is what I'm doing now and this is my thing and this is what I do. And I was still interested in epee at the time. I had only been practicing for a few years and wanted to get better at that. So I didn't get into the temptation immediately, even though I was very interested in what they were doing there. I then came across a couple of friends who didn't do it for very long in the late nineties 98, 99, 2000. A couple of people from work, we had started hearing, especially through the SCA crowd, that there was such a thing as late medieval combat. The Renaissance festivals were very, very popular in the Washington DC, Maryland area as well. We would go to the Ren Festival every year. And so we started playing with putting hilts on bokken and shinai.

GW: I remember. We were young, it’s not our fault.

AR: Absolutely, exactly. But you know, but it's what we had. What we didn't have, yet, because once again, I had not gotten interested enough to really try to find the people who were really doing this. What we didn't have were the sources. So all we really had was going to the Renaissance festivals, seeing what those guys were doing and going back and bashing each other with sticks.

GW: Longsword like objects.

AR: With sticks. That’s what they were. Sticks with a cross guard.

GW: So what changed?

AR: What changed?

GW: Yeah. You were just going to re fairs and bashing your friends with sticks and now there's like a decent collection of swords behind you and you actually practice historical martial arts. What made you transition?

AR: Well, here's the thing. The collection of and the interest in period weaponry predates my serious practice of historical martial arts. Why I'm really interested in historical martial arts is that maybe it comes from my time as an artisan. I'm interested in how a tool works and why it works the way it does and why it's designed the way it is. And the only way to understand why something was designed the way it was, is to understand how it was intended to be used.

GW: Yeah.

AR: So I come to the practise from the love of the object. And desire to understand the object. And I am very, very much a sword geek. I'm interested in knowing why this handle construction or this grip construction was used on this particular sword and not another. Why are we doing this? Because there are reasons. Some of them will be economic. Some of them will be fashion. Some of them will be mechanical. Some of them will be tradition. But figuring out the what and why of all of that requires you to play with these things.

GW: And Oakeshott understood that. Bless the man.

AR: The majority of the weapons collection curators that I have had a chance to exchange with understand that. That doesn't mean that they all do it. That doesn't mean that it's possible to do it with a lot of these collections. But as we move into an era, and we are in that era, where we understand enough about these weapons to make proper reproductions of these weapons and then go play with them.

GW: So do you play with sharps a lot?

AR: No, I do not play with sharps enough because I don't have time to play, period, enough recently.

GW: The way a sharp blade works is quite different to our blunt blade works, particularly when we talk about blade on blade. So when we're looking at how a historical sword functions, I think it's a necessary piece of the puzzle is to use the sharp ones.

AR: I completely, completely agree with you.

GW: Next time you go to Britain, come to my house and we'll sort you out with some sharps.

AR: We will do that. We will do that. The sharp on sharp thing is something that I am very, very interested in. I do not do simply, for lack of a second sharp, I trust.

GW: Fair. My solution to that was I bought two budget end sharp longswords and just re-grind them every six months. Because they do get messed up. I wouldn't do it with my beautiful sharps I use for solo training and test cutting or something like that. But I have a pair of sharps. The absolute cheapest way to kind of get started on this is just buy a couple of machetes.

AR: Yeah.

GW: I have a couple in the garden and I use them for like cutting down nettles. But also, you know, every now and then a bit of sharp on sharp practise because they cost about $2 each, these things and so are entirely disposable.

AR: However, I misspoke. Or at least I wasn't clear when I say that I'm missing the second sharp I trust, the trust is not the weapon. It's the wielder of the weapon.

GW: Oh, yeah. That’s fair. Don’t worry, I’ll look after you. I haven’t killed a student yet.

AR: No, no, no. That we can do. No. But what I mean by that is locally. Locally I do not have anyone that I can practice sharp on sharp with.

GW: You have to know that they're not going to panic.

AR: I would think that that is the primary thing. The panic is dangerous.

GW: I've done quite a lot of sharp on sharp stuff with students, in particular students I don't know. So like when I travel to places, I often do sharp on sharp with the students because it's their first experience of it. But the scariest such thing was at a roleplaying convention, I did a demonstration and then I opened it up so that anyone in the audience could come and do a bit of sharp on sharp blade work with me during the demonstration and I got a queue of about 30 people who wanted to have a go. And it sounds ridiculously dangerous, right? This is what we did. Firstly, I had about eight students with me. And what they were doing was they were keeping an eye on the audience and the whole thing was set up so that it was very obviously our space. So when somebody came to do the sharp stuff, they were entering our space and the first thing they did was a basic drill with blunt swords with one of my students, which was the thing we were going to do sharp on sharp with me. And then they got passed over to me. So firstly they had to queue up. They were entering a space that was clearly belonging to me and my students. They got filtered through this experience of doing blunt on blunt. So basically, if they were the sort of person who couldn't do as they were told that would have filtered them out. And then they finally get to me and because I have students literally watching my back and watching the audience. So I know that we're not going to be interrupted or whatever, I can give all of my attention to that one student in front of you and take you safely through the job. And it was probably what I would describe as a spiritual exercise. It was really useful for me. I had some people who'd been like doing martial arts for like 20 years, come up to me afterwards and say that the first time that they had done sharp on sharp stuff and it has opened their eyes to all sorts of things about their own martial art, which is like super rewarding. But I wouldn't do it again. Once was enough.

AR: Well, my main thing at this point is that I is that I really, really need to recreate the time to actually practise. I mean, forget the distinction between sharp, blunt, whatever. The last two and a half years, I have been practicing not enough, period.

GW: Okay.

AR: Well, just. Just running a business that depends on proper supply from the various countries in covid land and now in geopolitical land, it's taking a long time.

GW: I have to ask you about Black Armoury. So what made you want to start that company? All of us in the historical martial arts world have had the experience of not being able to find the right equipment and those of us that were around 20 years ago remember that there were no suppliers. You had to bodge together from either individual makers or make it yourself or adapt something that's been made for something else, you know? So what made you start Black Armoury?

AR: It started with the desire to restart practicing HEMA and discovering that there was a club in the town that I was telling you about that's 40 minutes from where I live. This was back in late 2014. Discovering that there was a club there and going up and starting to practise a little bit and realising that I didn't like the jackets that were available for myself. You know, they're perfectly fine. There were some SPES jackets in the in the crowd that I was able to try, which were just fine. But there was a little detail here, a little detail there that I didn't like. There were some PBT jackets that had different detail that I didn't like, you know, little things like that. And I tend to be a stickler for I want it just right. And so I had a person in the club who was sort of having the same kind of thoughts, and we had a prototype jacket made by someone local to us that was giving us sort of what we wanted out of a jacket. It grew from there because then it was, well, can we actually produce this thing? And the answer was yes. And is there interest in this thing? And the answer was yes. And people who were buying the jacket from us were saying, hey, can you also get this? And the answer was yes. And it started growing from there. And I remember I was telling you about my personality, which is, when I start something, I tend to go all in, which is extraordinarily dangerous. The first thing that I told this person who became my business partner, the very first thing when we started saying, hey, you know, why don't we just start a company and do this? The first thing I said was, yeah, but I've got my forge. I don't have time for this. I can help, but I can't do this.

GW: I know where this is going.

AR: Yeah, well, look at me now. It grew from there. We put together a small catalogue and a website, and I got more and more involved. And fairly quickly over the first couple of years, it became my primary activity. It coincided with a number of things. 2014, 2015, 2016 were the years where from the production side and the conception side, historical martial arts gear really started being pretty much there.

GW: Mainstream. Yeah.

AR: Well, mainstream and the production issues have been sorted out and a lot of design issues. It wasn't perfect, but a lot of design issues had been sorted out. And it was possible to get these things into the hands of the interested masses.

GW: I think a large part of that is the tournament scene. The tournament scene is like the engine.

AR: It’s the motor. So there was that on one side and there were a number of things going on in the restoration ironwork side of things. At that time, there was a slowdown for all kinds of reasons and public finance reasons and whatnot. That sort of created the perfect storm for me to make a shift into Black Armoury.

GW: Okay. So you basically gave up the architectural ironwork to do Black Armoury full time.

AR: I progressively slowed down until 2017, 2018, when I put the hammer down professionally and reserved the forge time for the personal stuff.

GW: Okay. Yeah, because I mean, you're not going to stop hammering iron. It’s like me, I'm not going to stop cutting bits of wood.

AR: Not possible.

GW: Yeah. How would you?

AR: It’s part of me. Doing it professionally, however?

GW: I used to be a professional cabinetmaker, and I hated it. It was the wrong job for me. It's the right hobby, it is entirely the wrong job. It made me miserable.

AR: Absolutely. So Black Armoury started from the idea that we wanted something better for ourselves. It grew from there into people seeing, we're talking about the Arcem jacket here that we’re still selling.

GW: Why is it called the Arcem Jacket?

AR: Arcem is one of the declensions of, and this is why we don't call it this, “Arce” in Latin, which is the citadel and was sort of a natural name for that which protects protective gear.

GW: Okay. So sort of like “the castle jacket”.

AR: It's sort of the castle jacket. Yeah, exactly. But since the Latin word is Arce and we wanted to sell this in English, it just wasn’t working out for us. So we said, okay, let's work with one of the declensions there. So in the end, it is the declined arse.

GW: Okay. A declined arse. Good to know. Get your declined arses from blackarmoury.com.

AR: Exactly. That's why the Arcem and that’s why the Arcem logo is a little rampart.

GW: Okay. All right.

AR: Initially it was that idea of protective gear. We do have other things under the Arcem line.

GW: You sell my books too.

AR: Oh, well, yes, but that's not under Arcem.

GW: Okay.

AR: We have brands under Black Armoury. We’ve got Arcem and Dohema. Dohema, which is an obvious kind of nonsensical name. But it's “do HEMA”. So yeah.

GW: Fair enough. Okay. So one of the things that you guys specialise in is new ways of solving old problems, like I’m particularly interested in your complete suit of armour in plastic. And you've got Daniel Jaquet consulting on this. And by time your episode, this episode goes out, Daniel's episode will have come out a few weeks before. So listeners can go and listen to Daniel. If you've never heard of Daniel Jaquet, then you don't know anything about medieval combat. In the armoured combat world, the man is a god and rightly so.

AR: Come on, it's Dr. Dan.

GW: Exactly. So, he's consulting on it. Your basic idea that is to produce a full suit of gothic, shall we say? So let's say 14th century.

AR: Yeah.

GW: Late 14th century armour. But entirely in plastic.

AR: Entirely synthetic. Let me just jump back to the way you phrased it initially. New solutions to old problems. But I wouldn't say it quite that way. Because the old problems are solved.

GW: Yeah.

AR: The original designers of these things, whether it's the armour, whether it's the weapons or whatnot, had solved the problems for a long time ago. What we're doing is twofold. One is applying new materials to old solved problems in one sense. And bringing the price down to an acceptable level for more practitioners of historical martial arts by applying those new materials. So the idea behind the synthetic harness is to use the old solutions to the old problem which are perfectly well adapted.

GW: Yeah. So the design is basically copied off the historical originals.

AR: As much as is possible. Yes. But to produce them in a way that allows for several things. One, by having it in a synthetic material, we can more easily semi mass produce these things. And I don't mean mass produce. Theoretically we could mass produce them. And if we were to jump to the very end of your interviews and have the million dollars to do just this, yes, we could technically mass produce these things, but it's a huge investment and not worth doing. So semi mass produce, which means still a lot of hand manufacture, but in the materials that is a lot more forgiving and requires a lot less time than steel or iron. That's one thing. The other thing is that beyond the cost, full steel harness requires a certain amount of getting used to. It requires a certain amount of physical conditioning. Even though these things are wonderfully balanced and distributed across the body. You still have those kilos and you still have that physical conditioning that needs to be done on. One of the things that Daniel was telling me when we were starting to do this, he said, it took me six months of wearing my harness 2 hours a day intentionally, to develop the tiny little muscles that you don't even know are there to be able to actually wear this thing and move in it in a combat sort of way. So that's not the kind of physical development investment that the average HEMA practitioner is going to be able or willing to put in.

GW: Most people simply can't go to work in their harness. Which is what you need to do. I mean, to get used to it, you need to put it on and wear it. I mean, when I was conditioning to my harness, I would sometimes get into it and then just spend the morning in it doing woodwork in my armour.

AR: Yeah. Or for people like Daniel who go to airports in their armour. I love him. But in any case. So there is that aspect as well of lowering the bar is not just about making something that is more affordable to more people, but is also more accessible simply physically to more people.

GW: Okay.

AR: Yeah. So the idea there was to see what we could do to have something as historically accurate in its design and in its mobility, in the targets that it offers to the practitioners in as many hands, or in this case, on as many bodies as possible.

GW: Okay. So is it actually available yet?

AR: Yes and no. Yes, it is. Our partner for this on the production and on a lot of design is Michael Zavatskiy. Michael is Ukrainian. Michael is in the Ukraine. His workshop is in the Ukraine. So what does that mean? That means that we get into the geopolitics that I was talking about earlier, and I'm calling it that. I'm just calling it that. It's a difficult situation. That said, I am hugely impressed with my several Ukrainian suppliers. They are still working. They are still producing. They are still shipping. Specifically, the armour has been slowed down a bit in its production because Michael has used his stock of synthetic material. The same material that we used for the armour to produce other things that are required for the defence of his country. I was hesitant initially to talk about it, but since he has advertised it all over Facebook, Michael is producing kneepads and elbow pads for the Ukrainian military, using the stock of plastic that we're using for the armour.

GW: I don't think anyone can reasonably object to that.

AR: No, there's no objection to that.

GW: Apart from the Russians who'll be very upset.

AR: And even so. What are what are we what are we protecting? We're protecting elbows and knees against.... Yeah, exactly. But in any case, so there was a there's a bit of a slowdown there. And it's simply a raw materials issue that will be solved. Michael also produces our synthetic polearms and those are still being produced and shipped.

GW: Okay. And one thing that I have tried to encourage my listeners and readers to do, is now is a really good time to buy stuff from Ukraine. Particularly from the historical martial arts supplies in the Ukraine because every drop of foreign currency going into the country is doing something useful.

AR: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. And one of the things that we make, we're not going to go into all the commercial agreements that I have with various suppliers and whatnot, but specifically regarding the Ukraine as long as this situation lasts. Everything that comes in on purchases of Ukrainian material goes to pay the Ukrainian upfront so that the cash is flowing, so that it's going in, so that it is there. So that's important. And quite frankly, since we're talking about this situation and we're talking about historical martial arts, it's not just the Ukrainians, it's the Russians as well. Our Russian producers, you know, people like Kvetun and whatnot are put in a terrible spot by the situation as well.

GW: They are being absolutely screwed over by their government. No question.

AR: Absolutely. So, you know, it's a matter of HEMA solidarity. And it's not at all a national thing.

GW: Yeah, I couldn't agree more. So people can actually go to a website and if they want to just order a set of this harness now.

AR: Yes, they can. And it will be delivered eventually. This is just going to take a little bit more time than we had hoped.

GW: So but honestly, long lead times is kind of par for the course with historical martial arts. I mean, I remember back when we were dealing with Del Tin, like in the nineties, the one thing I loved about Del Tin, nice designs and swords, but they said, order now, and you will get your sword in ten months. Right. That was their order time back then. And the thing is, so many smiths, so many suppliers would say, order now and you'll get your thing in three months. Okay. But thing is that three months became six, became nine, became 12. And eventually you might get your thing two years later. Whereas Del Tin, they said ten months. Ten months later, you got your thing, every time. Waiting a bit, that’s fine. You’re a craftsman. I had some woodworking saws made by Florip tools in the United States. He's a retired Marine, who has gone into making these fantastic handsaws. They are beautiful. And yeah, they take eight months, nine months to get it. I don't care. Because when they arrive, they're fabulous and exactly what I ordered and totally worth both the money and the wait. So you don't need to be embarrassed by long lead times, I don’t think.

AR: Well, it is something that I'm trying hard to manage at the moment. And it has been a rough ride as far as managing a business of this type. Well, you know, COVID was not the biggest issue. 2020, 2021, we had some slowdowns from time to time. But it wasn't a big a big problem. Since November, December, it's been complicated in the sense of we ourselves never know what to expect as far as when we can get delivered from our suppliers. We can't make promises. And yet we kind of have to. There's that aspect of things. It's raw materials. Sometimes they're available, sometimes they're not. Sometimes they're available with one supplier, but not another. So we don't know what's coming in and when. Shipping has become all over the place. The same package will sometimes take 24 hours to get to a certain location. Sometimes it'll take a week.

GW: I've had an order of books I sent to a bookshop in Germany sat in Frankfurt Airport for six weeks before they would send it on.

AR: Before they remembered them. Yeah.

GW: Yeah. It is absolutely crazy. Brexit has not helped.

AR: Don’t get me going.

GW: I didn't say that. I didn't say that. But like, I have a sword coming from Ukraine and I know it's shipped. I've got the message from Royal Mail saying it's arrived in the country and it got from war-torn Ukraine to Britain in less than a week, and it's been sat in Britain for about three weeks now. Because apparently lorry drivers are demanding to be actually treated like human beings and paid properly or something like that.

AR: So yeah, I mean, it's complicated in that regard, but trying to put things in place.

GW: So now is a difficult time to be a supplier.

AR: Now is a complicated time to be a supplier. Things are happening, but it's just a lot more work to manage than it used to be and it should be. And we will get back to a sense of new normal and learn to manage through all the situations and whatnot. The other thing is that we started this company. There were two of us. My business partner decided to go off and do other things in late 2019. So I had to sort of readapt things to working that. Covid actually help in that regard because it sort of gave the company the breathing room to rethink things in early 2020. So yeah it's complicated for the suppliers and the producers. Therefore it's complicated for us to manage the situation, especially as far as communicating, yes, you will have your order at this time or at that point. But we're putting things in place and we'll get there.

GW: Okay. Excellent. So, you know what’s coming. You've decided to become an architectural blacksmith person, you went and did that. And then you decided to start a historical martial arts company and you went and did that. What is the best idea that you have not acted on?

AR: Apart from investing in Apple stock in the early 1990s.

GW: Did you actually have the idea to do that? I didn’t.

AR: I did. I absolutely did.

GW: And you didn’t do it?

AR: No, I did not. Yeah. Well, water under the bridge. That's a tough one for me. I probably have a number, but I'm very much of a “put my head down and run towards the wall and we'll figure out whether there's an opening when we get there” kind of guy. So I don't usually know whether a good idea is a good one until I've actually tried it.

GW: Yeah.

AR: So identifying a good idea in hindsight is, I don't know. Things maybe that I wish or that I would have liked to have done by now but didn't, regardless of whether it's a good idea or not. Riding horses. I have been telling myself I will start riding next year since I was like 18.

GW: Are there horses near you?

AR: Oh, gosh. There are horses everywhere. It’s definitely riding country.

GW: Just do it. Yeah, just do it.

AR: I will. I will.

GW: Not next year. Next week. Seriously, the only reason I don't ride horses regularly is because my eldest child is seriously allergic to anything with hair. And so it's just not practical for me to be coming home covered in horsehair. I would literally have to strip naked at the front door every day, every time I came home. The neighbours would object.

AR: Seriously in that regard, Guy, I hear you. If it was a matter of saying, I want to get on a horse and ride around in a touristy kind of way for a couple of hours, I'll go tomorrow morning. Investing the time in learning to ride properly is unfortunately not for right now. It really isn’t. I don't have the time to pick up a sword right now.

GW: You can combine them. Pick up a sword on a horse.

AR: Yeah. I hear you. I hear you. I am making excuses. But trust me, they are good excuses.

GW: Here’s the thing. I've been wanting to fly planes for ten years since I first stumbled into a trial lesson as a complete accident. I've never been interested. But I went on this trial lesson and it blew my mind completely. But I never had the money. You either have the time or the money, because it is very unusual to have both. So by the end of last year, I realised I did actually have the money to start flying properly. And so I just said, fuck it, I will make the time. And I have let all sorts of things slide, like I should be way further ahead on writing my next book. But every time I go flying, and I try to go at least once, sometimes twice a week, it's most of the day because it is most of an hour to get there. There's the briefing and then flying. And then after the flight you have a debrief and then all sorts of fiddling about. For every hour in the air takes me probably 4 hours out of the day. That time has to come from somewhere. But you know what? Totally worth it. Totally worth it. I can think of a million things you could just let slide just to get yourself on a horse. And I think you would not regret it. You should do it. You may be letting the perfect be the enemy of the good. Like, yes, absolutely. Long time goal. Learn to ride properly. Do the flying changes and all the other gubbins that come with high level riding. Absolutely. That should be the goal. But there's much value to be had in simply showing up, doing the necessary stable work, getting on the horse, riding around the field for an hour, and then getting off looking after the horse and going home again. Time spent in the saddle is never wasted in the same way that time spent flying a plane is never wasted. It doesn't have to be all formal instruction and doing it perfectly.

AR: That's perfectly understood and makes a lot of sense.

GW: So, next week. Excellent.

AR: Once I figured out how to string more than 45 minutes in one stretch.

GW: We've been talking for 90 minutes. You should have said, Guy, I'm terribly sorry. I can't do the interview with you today. I'm going riding. And do you know what I would have said? I’d have said good choice, sir.

AR: That is fair enough. I'll tell you what. Why don't you delete the last hour and a half?

GW: No, we’ve got it now, we might as well keep it.

AR: Absolutely. So. Yes, riding is something that I will do. Absolutely.

GW: Next week.

AR: And probably a number of other things. I'd say the reason I chose that one, I think is that's the one that I can say yet and that I will do.

GW: Okay. I know quite a few people, Jessica Finley being one, who have taken up riding fairly recently. So, you know, in our middle age, because it wasn't available when we were younger or just wasn't a thing back then. It's transformative. It's just one of those things that's fundamental because, you know, the thing is we are not getting any younger. Our hips are not getting more limber with age.

AR: Agreed.

GW: If you leave it too late, you might end up not in a physical condition to do it. Times a fleeting.

AR: Yes, sir.

GW: Right. You have your marching orders? Come on my show Anthony and I’ll tell you what to do with your life.

AR: Yes, sir!

GW: Okay. My last question. Somebody gives you a million quid to spend improving historical martial arts worldwide. Of course, what you do is you open a stable. No? What would you do with it?

AR: What would I do with it? I would, because in itself it would be not sufficient, unfortunately.

GW: You can have as much money as you want.

AR: I would use it to get the research and legwork and probably initial scripts done for a historically accurate miniseries.

GW: Okay.

AR: Okay. Here's my thinking. And if somebody wants to take this one and run with it, please do it. But please do it right. Okay. Paulus Hector Mair.

GW: Oh, yes.

AR: Okay. Paulus Hector Mair is the perfect subject for a historical martial arts period series. It's got everything. It's got the intrigue. It's got the, how were manuscripts produced. It’s got how is this artwork done. It's got the fencing schools. It's got fact that Joachim Meyer was teaching and practicing a three day ride from Paulus Hector Mair from there at the same time. So we can throw him in there as well. There are all kinds of things. There's the Fechtschule. It’s all there.

GW: Just for the sake of listeners who may not know who Paulus Hector Mair is, could you summarise the high points of his life for us?

AR: Saint Paulus…

GW: He was not a saint.

AR: No, but as far as I'm concerned, he's the patron saint of historical martial arts.

GW: Okay. I thought that was Michael Chidester, but carry on.

AR: No. Michael Chichester is the current cleric of martial arts, but Paulus Hector Mair was a Bavarian martial artist. But in the late 16th century, he died in 1579.

GW: How he died is important.

AR: Oh, absolutely. And we'll get there. But he produced a monumental work that was designed from the ground up to preserve martial arts that were already starting to fade by the time he did all of this. Which is why I'm saying that he is the patron saint of historical martial arts, because he was a HEMA guy. He was a HEMA guy. It's what he did.

GW: And he was also the only one who was deliberately recording what was as opposed to what is or what may be.

AR: Exactly, and probably travelling around a little bit to find the more obscure stuff like, you know, he's got agricultural scythe combat. It's fantastic. And he's got his polearms and he's got the longsword. It's all in there, it is absolutely monumental. And he was also an elected official in his town. And producing this kind of manuscript was extraordinarily expensive. He was a huge collector of manuscripts and books as well. So putting that library together and financing the production of this monumental work cost a lot of money. And that money was, shall we say, well, embezzled from the state coffers.

GW: Let’s not beat about the bush. He stole.

AR: Exactly. He stole the money. He did. He stole the money for which he was hung in 1579, executed as a criminal, which he was. But see, that's where the series is fantastic. Because it's even got the intrigue and the potential character who is jealous of him and who comes to light.

GW: Yeah. Who did the investigation?

AR: Exactly. And his secretary in the mayor's office who discovered this.

GW: And he wasn't doing it just for himself. He wasn't he wasn't stealing the money and spending it on, you know, beer and skittles. He was stealing the money so that he could collect these manuscripts and create this monumental historical martial arts work. I mean, he's basically a martyr to the cause.

AR: Exactly. And so his story, for me, is the perfect backdrop because of the intrigue that could also go with it, because of the fact that he's not only a martial artist, but that he's looking at other martial artists and producing these works and whatnot. To have an interesting miniseries like the ones that we like to see, the Tudors and the Borgia and all of these things.

GW: Which are crap, I can't stand them.

AR: Yes, but fair enough. But that's the whole point. To do something that's popular like those. But that shows the origins of our world, our martial arts world.

GW: And do it accurately.

AR: And do it correctly.

GW: With even the right on work on the doors.

AR: Exactly. The right nails. Because there is enough in this story to not have to make shit up.

GW: Yes. Now, the real trick there will be getting the right producer and the right director because with the wrong producer director, they'll make shit up anyway.

AR: Well, of course. Anyway, it's fantasy money. So it's a fantasy project. We'll get it done right.

GW: It's a bloody good idea. That's a really, really good idea. Okay, people listening. I think if any of you is actually a TV producer, come talk to us, we’ll sort you out. This could be amazing. This could be bigger than Game of Thrones. Well, unlikely.

AR: Well.

GW: Better than Game of Thrones, indisputably. Bigger? Probably not. Brilliant. Well, thank you very much indeed for joining thing. It was lovely talking to you.

AR: It was a good time. Thank you very much.