Episode 117 Sword Business with Jo York

Share

You can also support the show at Patreon.com/TheSwordGuy Patrons get access to the episode transcriptions as they are produced, the opportunity to suggest questions for upcoming guests, and even some outtakes from the interviews. Join us!

Jo York is a provost of the Hotspur School of Defence, which is based in the north east of England, and an entrepreneur in her work life, as well as an avid listener of this show.

Jo talks about her home town of Knaresborough, with its annual Bed Race. There are pictures here: https://www.bedrace.co.uk/gallery/2022-race

And this is the fabulous Yorkshire-accented raven at Knaresborough castle:

Jo works with start-up businesses and has started her own businesses too, so we talk about what makes a good idea for a viable enterprise and how to go about it. The book Guy mentions is Don’t Trust Your Gut, by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz and the book Jo recommends is The Mom Test: How to Talk to Customers and Learn If Your Business is a Good Idea when Everyone is Lying to You, by Rob Fitzpatrick.

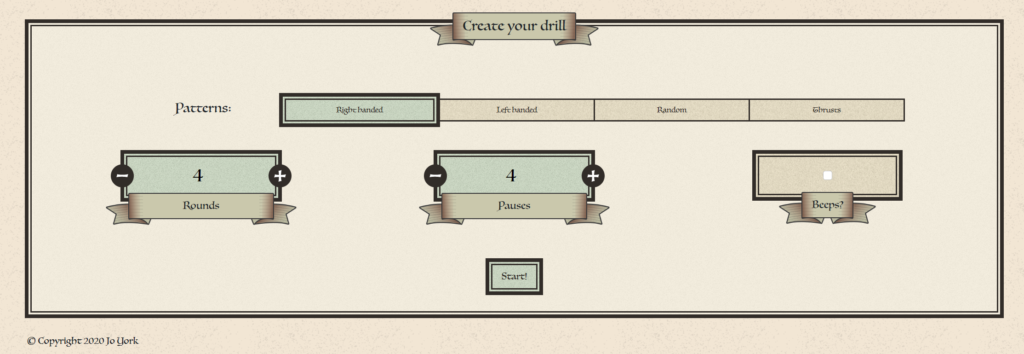

Check out Jo’s cutting square website at: https://cuttingsquare.com/ This interactive cutting square tells you where to aim your next blow. There is a left-handed and right-handed option, and you can set the tempo.

Transcript

GW: I’m here today with Jo York, who is a provost of the Hotspur School of Defence and an entrepreneur in her work life, as well as, she says, an avid listener of the show. So without further ado, Jo, welcome to the show.

JY: Thank you very much, Guy. It’s great to be here.

GW: It's nice to meet you. Your name is familiar to me because you have bought a lot of my stuff.

JY: I buy everything. I'm sometimes the first person to buy some of your stuff.

GW: Which is why it's like, oh, I made a sale, oh, It’s Jo again. Fantastic. Okay, so just to orient everybody, whereabouts in the world are you?

JY: I am in lovely, sunny today, Whitley Bay, which is in the northeast of England, near Newcastle.

GW: Okay. Is that where you're from?

JY: No. Originally from Yorkshire, near York. Enough for it to be really confusing when trying to pre-order things in shops when you leave your surname. That's how close to York.

GW: Okay.

JY: Knaresborough is where I’m actually from. Which if you want to know what a medieval England theme park would look like, Knaresborough is pretty much it, I guess.

GW: And York is a close second.

JY: Definitely. But it doesn't have a witch, you see. Doesn't have a witch.

GW: Doesn’t have a what?

JY: A witch. Weird fact. So Knaresborough was the first official tourist attraction I think in the entire country. And it has a place called Mother Shipton's Cave.

GW: I’ve heard of that.

JY: Yeah, the woman herself said some things that she probably shouldn't have, but the Victorians took it and ran with it and made poems about how she predicted lots of suspiciously very Victorian inventions. Oh, we've just found these things she talked about, like metal ships and machines and things like that. So yeah, I was destined to love history I think growing up in Knaresborough.

GW: I spent last weekend in Bath, which is like a time capsule for the late 1700s. It’s very pretty. But I think up further north, it's less preserve to be preserved, it’s more preserved just because that's how everybody likes to do things. You get a feeling that Bath has been artificially preserved by rich people deciding they don't want it to change. Whereas I think maybe York, that sort of area, it’s more like this is there's just no reason to change it.

JY: Yeah. I mean, sometimes there are reasons to change York. Drive around it, that's a terrible idea, but yeah, it's good. And Knaresborough has done a really good job of keeping a lot of its charm. I was back there last weekend, actually, because we have a thing called Bed Race. So Knaresborough is on a crag and it overlooks the river Nidd and has a very famous view of the viaduct with the bridge and what we do is we get like, imagine a hospital bed with slightly bigger wheels and we race them. I say ‘we’, I've never done this, although I have sort of committed to it now. And we race them along water side, up the crag and it's a really steep hill.

GW: Is somebody in the bed?

JY: Yeah. So you have somebody sat on the bed and I think, I think there's about eight people, this might not be right, but there's a few people, eight people that are allowed to push it. And it's a time trial and they go all the way up along the water side, all the way up this crag, round the marketplace, down the high street, round the corner. And then if it's really good weather, through the river at the bottom and it's a time trial and there's a fancy dress element to it as well.

GW: That sounds like a lot of fun. I think I would be best placed on the bed. I don't see myself as running up and down hills pushing beds myself.

JY: Yeah, it's incredibly, incredibly difficult. So I was back there last weekend actually, which is probably why it's very much at the forefront of my memory on history and stuff. I would definitely recommend people go, it's a really good day trip. There's even a talking raven, what else do you need, in the castle courtyard? It's very Yorkshire. It's hilarious.

GW: So there’s a talking Raven in the castle. And we are talking about a genuine raven, not mechanical?

JY: No, no, it's real. It's a real bird. I think one of them actually might be a South African crow or something, but it and it's hilarious. You can honestly look this up on YouTube and it does swear at people, but it's famous for saying “You alright, love?”

GW: You don't actually work for the Yorkshire Tourist Board, do you?

JY: No, but I could, I mean it has my name in it, so, you know.

GW: So how did you stumble upon my old friend Bob Brooks and the Hotspur School? How did that happen?

JY: So I'd been thinking about doing something like this for a couple of years. I did loads of martial arts in the past. I did Judo as a kid. Everybody does that. So it probably doesn't actually count, and capoeira for a bit. Oh, do you remember that? Do you remember that time in the nineties where you couldn't buy a mobile phone without seeing capoeira? Like, I want to do that. That looks cool.

GW: Fighting while upside down.

JY: I know, right? Wearing massive trousers. There is a theme in my martial arts of can I wear massive trousers in this, to be fair.

GW: If you can't, why, you can do it.

JY: I know, right? So my gateway into big trousers started with capoeira. And then I did aikido for about ten years and I got to first Dan, then I actually did my first Dan twice and again, so when you get to your black belt, which is your first Dan in Aikido, you basically earn your trousers.

GW: The Hakama, yeah, the great big black squishy things.

JY: Presumably up to that point, you've just been training in your pyjamas for that whole time and now you are allowed to get fully dressed.

GW: That seems to be the way it is.

JY: Yeah. And I stayed and I got involved because I was like, I want a pair of those. That's great. So obviously a lot of it is open hand and un-weaponed, if that's a phrase and open hand fighting. And so that's good. But my favourite bits were always when we brought out the daggers or the staff which is called a jo. So obviously that's an affinity. Or the bokkens. And I was always wanting to do more of that and I would turn around and go, this is great. And everyone be like, mmm yeah, can we just go back to the normal stuff and fine. And so then it got a bit political, a martial art getting political? Surely not.

GW: Really? Never heard of that before. In what way political?

JY: My main instructor is one of my best friends in the world actually, and he's been my business partner for years. When he needed Aikido most, I'm not sure if this is engineered this way, but it seemed like the head of the organisation basically took it away from him. But because I was running the business at the time, I didn't realise actually how, how much friction there was into this still being a thing for him that he needed in this very, very difficult time. And I only found out about it over like subsequent years. And it just got harder and harder. I mean, I went to training because I saw my friends there, but it just got harder and harder to want to progress in that environment. This will probably be cut out but he's quite a Marmite character, that particular guy. Other Aikido schools are available.

GW: Yeah. For the Americans who don't know Marmite, Marmite is something you either absolutely love it or you can't stand it. Hence Marmite character.

JY: Yeah, actually, no, that might not be true. I think he's just rubs people up the wrong way. I think that's probably not even Marmite. I think you like him for a while anyway. Other Aikido schools are available, but yeah. So I learn an awful lot about body mechanics and which I think is give me a really good head start in the world of HEMA. But I was looking for something else that was somebody, a teacher that I could really like, not believe in, that sounds weird, but like a teacher that I liked, that I trusted, that I knew that was good. And I walked in and I met Bob and I'm like, he's the opposite of that guy. This is somebody that I really like that I trust. And just the way that the first time I saw him cut like a straightforward oberhau with a longsword, I was like, he knows what he's doing. This is different. I'm going to learn so much here. And then they let me pick up a sword and I'm like, I'm staying. Take my money.

GW: Yeah. I mean, I've known Bob for more than half my life. He's a thoroughly good bloke. Yeah, I would trust him completely. I mean, we don't always agree on absolutely everything how swords should be used. I mean, he keeps banging on about this German shit instead of coming to the true Italian religion. I didn't say that.

JY: I know that you disagree on the Italian stuff as well, Guy, so that's fine.

GW: Yeah, but no, he's an absolutely solid bloke, for sure.

JY: Yeah. And I think when you meet somebody that really knows the subject, this person has forgotten more than I will probably ever know about this subject. And I can learn so much from this person. And he will tell you. I mean, you know, Bob, he is a talker. It's the asking him to stop telling you about the thing he wants you to know that's the issue, not the actual thing. So yeah, I've learnt an incredible amount from him. The reason that I wasn't sure about whether I wanted to do HEMA or not is because there's a couple of other things. So there was another sword group in the centre of Newcastle who is more of like a performance thing. I knew that there was this historically accurate and well, everyone's going to neckbeard if I say historically accurate, ‘historically based’ as much as we can.

GW: Shall we say, ‘working towards historical accuracy’.

JY: Yes, yes, exactly. This other thing and I found out we could do sparring with it. And none of my martial arts have ever been stress tested. You know, Aikido is very much “I will stab you now”. Because you have to commit to it.

GW: Yeah. I have a friend of mine who's a very, very good Aikido person. I think he’s fifth or sixth Dan anyway. Yeah, many moons ago when he was younger and shall we say, more foolish. He would go down to the dodgier bits of Helsinki on a Saturday night and not pick fights with drunks, but let drunks pick fights with him and then very carefully, gently, lower them to the ground in such a way that they weren't injured. But he actually got to practise doing his thing against someone who wasn't cooperating. But he had to go to the dodgier bits of Helsinki on a Saturday night to find that, it wasn't available within the mainstream training of the art. And I think that that can be a problem for some people.

JY: Yeah it is. And I mean, so when people are being more generous about Aikido and obviously there’s good Aikido and bad Aikido. And the problem with Aikido is there's so many different styles. So there's a very soft style that's very much more like interpretive dance and it's a bit more like Tai Chi and is all about that body mechanics and that sort of control over your body and moving with purpose all the way up to very direct techniques.

GW: My top, best, unarmed sparring I have ever done right was with an Aikido guy and we met in Dallas. I don’t think it was the first time we met, but it was the first time we played together. His name was Joe Alvarez and this is in 2006. 16 years ago and it's still in my head as this amazing moment. And we found this kind of padded squash court area and we just went for it. And I was doing like kung fu stuff and boxing kind of stuff and kicks and whatnot and I mean, he's the only Aikido person I've met other than my Helsinki friend, the only Aikido who could actually handle multiple jabs to the face, no problem. Because they don’t normally train it. That was just glorious moment where I had come in for something and he'd ended up doing a sacrifice throw. And as his shin came up towards my groin, as he was throwing me over his head, as he fell backwards, I caught his shin between my own shins, which propelled me further away. And I rolled, turned, and got we got straight back into it. It was bliss.

JY: Brilliant. I love it. That's the thing, isn't it? That's the beauty. So the criticisms about Aikido is, yes, you have to learn how to receive the technique.

GW: Sure.

JY: But part of that is so that the other person can commit to doing that technique. And the trust that you have to have between the person doing the technique and the person receiving is huge. If I'm attacking somebody, I have to trust them not to kill me and they have to trust me to do the exact break fall or whatever. They need me to not die or lose something important like the functioning use of a hand or something like that. And it's beautiful. It is beautiful. But I think a lot of that gets lost in, like, can you use it on the streets?

GW: Yeah, yeah. What streets do you live on? I mean really. My top tip for street defence is live on a nice street. Don’t go to the nasty ones.

JY: Yeah. What Aikido’s been very good at teaching me is don't be where the attack is. If that's a couple of inches out the way, great. If that's in a completely different room, better, if that's by some lifestyle choices that you have the privilege to make, even better.

GW: Exactly.

JY: So yes, Aikido. I can't remember how we got there. Why did you get back to Aikido.

GW: Because we were talking about not being able to spar.

JY: Yeah. Not being able to spar. That's right. So I was looking for something where I could stress test because I've never had that before, and so I was looking around and when I realised that we could do and sparring, varying different degrees, they were competitions for this. I thought that was interesting, I hadn't done that before. And so the sheer span of what is available to you in HEMA, not only like weapons, historical periods. If you just love looking through historical texts, you can look at the pictures, that's great. And if you really just like stress testing at speed and you don't care about technique, there are tournaments for you. There is the whole thing and I just thought that was absolutely fascinating. And then I think it took me, like all these things, I'm not going to put my work hat on now, and so you talk about in marketing touch points, right? I had a friend that went and trained with Bob years ago and said, you like swords and medieval stuff, you should go and train there. And I thought that sounded quite interesting. And then there's a couple of other people that talked about it. And then I saw the BBC documentary where Bob was talking about the project that he'd done with the University of Newcastle, with the Bronze Age stuff.

GW: Oh yeah, the damage to the edges on Bronze Age stuff.

JY: I think the documentary was called Britain's Pompeii.

GW: Something like that.

JY: Yeah. I was watching it and I said, oh, that's that guy from Newcastle. So I immediately emailed him and said, can I come along and train. And so it did take a little while and then of course when I walked in I was like, why didn't I do this ten years ago?

GW: To be fair, I would say of all the martial arts, historical martial arts generally are improving and developing faster than any other martial art I've come across because we're not constrained by what the Masters did. My teacher does this, my teacher does that, well so what? Our teachers have been dead for centuries. If you think of like martial arts generally, you've got tai chi over here where the way a lot of people do tai chi, there's no real contact. Then you've got maybe Aikido and then you've got some of the Kung Fu stuff, then you've got some Japanese stuff and, and there’s tournament karate and there's like demonstration karate where they basically they judge you on how well you do your forms. And there's if you like, Okinawan Samurai Street Combat karate, a traditional thing. So you have all of these all of these varieties of different martial arts with tournament ones and internal ones and ones with no sparring and ones which are all sparring and all that breadth. We have all of that breath within historical martial arts. Some clubs just care about tournaments and they train for tournaments. Other clubs just care about getting the historical stuff right, and that's what they do. Most clubs have some kind of blend of these things, but we're not constrained by our teachers in the same way that modern traditions often are. So you don't have that, well, in our style, we don't do this. I might say, well, in my club we tend not to emphasise tournament stuff. If you want to go do a tournament, that’s great, fine. We suggest maybe going to train with these guys for a few weeks before you go to the tournament, because they are really into the tournaments. And it's still all historical. It's all under that umbrella.

JY: I think, again, thinking about my time at Aikido, even in my main class where maybe there was about 20 people and the depth of skill there was exceptional. I was very, very, very lucky to train with those people. So if we take one specific technique, there would be three or four different ways of doing it. We'd say this was like the first pin or whatever. And so in Aikido language, you've got ikkyo, nikkyo, first pin, second pin, whatever. But there’s one of them, a particular joint lock, which I won't go into now but there are lots of different ways to do it, lots of different ways to emphasise different parts of the underlying principles. And so I would often talk about, oh well this is how this person does this technique because they’re taller or their limbs are taller, or their hands are like this. This person does it somewhere like slightly differently because they're working in a different body with different preferences and being able to pick apart, this is the same underlying principle with a similar name, but it's all the same thing. It strips off all of that like need to go I think actually you'll find you move your finger here, this is the actual technique. It's an underlying principle with like tactics on top. And I think that often gets missed in martial arts. And you're right, it's like, no, this is my style. And actually it's your own personal style, right? You have individual parameters of how your body works, what your preferences are, what solutions you'll find in that particular second. And there's tweaks that you can try and some will work for you and some won't. And that's applicable to every single martial art.

GW: Yeah. And if you look at, for example, Fiore, medieval Italian stuff, the techniques are called ‘plays’. It's not because it's no consequences playing around, it is because there is play within. If you are doing this action, if you do it exactly the same way every time against every opponent it is going to fail sometimes because you have to adapt it for different opponents or different specific contexts. But the idea is this is the idea. This is the technique. This is the principle. In this particular context, it looks just like this. So we have the canonical form of the play, which is exactly like the book with exactly the same setup. And it's all specified. But then once you've got it, in that context, you're supposed to play with it and figure out how you would make that idea work in different contexts. And in some contexts it won't work at all. In other contexts it would work even better than it does in the canonical play. You’re supposed to play with it.

JY: Yeah. And I think a lot of people lose that. They look at the pictures and go, no, no, my foot needs to be exactly here.

GW: Which when you do the canonical plays, it’s true. You have to know the canonical plays so that you have a physical example of the principle in practise. So you know that, okay, this is supposed to work in exactly this situation and you've got to get it to work in that situation and you got to get it reasonably right so that you can actually see it. So you can see the principle. But then if you happen to have the wrong leg forward, but your opponent’s sword is under your control and your sword is in their face. That was definitely correct.

JY: Absolutely. Yeah, totally agree. And yeah, I mean, whilst we're talking about Fiore, I think one of the things that I think is interesting about Hotspur and the way that Bob put the structure around it is that we do like almost like a hundred year period. So we do lots of different weapons, but we do lots of different sources as well. I really enjoy looking at looking and comparing the sources is like, why does Vadi say this is important and under what context? Why is he emphasising these bits and Fiore does it this way? And it's not just a yes, there's a time period and there's like maybe a different style of fencing, say, with Faulkner or whatever. And it was more of like a tournament fencing, it's more like a Fechtschule environment, whereas like Talhoffer definitely wants to kill you. But they all have underlying principles, they are all talking about the same things, but they're describing them in different ways. And I think once you can piece them together like that, you're like, ah, this is that thing that I need to do, what am I doing? I'm opening my hips. And for instance, Fiore might do it by doing a step across to open up the hips and then turn. Talhoffer might do it by like moving the back foot in a wind, but it's the same principle of like, what are your hips doing? What is your body doing? How can I influence what's happening in a bind by moving other bits of my body around it. So Vadi will talk about the knees being keys. So that is exactly the same as like same principle as like manipulating your body and how you describe that, people would do it differently, but it just opens up this whole world of like tinkering with individual bits of technique and then working that whole body together. I just find it absolutely fascinating.

GW: Yeah. So what period does Bob cover?

JY: Mostly 15th century. Fiore up to Faulkner recently has been like the sort of latest one that we've been doing. I do other things.

GW: When was Faulkner? I’m not familiar.

JY: That is a good question.

GW: It's been a very long time. I should just point out that's that Jo just took down Captain of the Guild, which I think is Christian Tobler’s?

JY: Yes, it is. I don't know. Christian will probably be able to tell us. I think it’s very early 1600s.

GW: Because you're saying like 1400, by my recollection, Faulkner was late 16th century.

JY: Anyway, we do that. It's not early enough for poofy pants. So it's definitely more 16th century. I really, really enjoy that looking at a complete system and then working out what it is, what does it have in common? Why is it different? What are the different tactics to solve similar problems? I find that absolutely fascinating. Rather than just concentrating on one master’s work, which I know you can spend a lifetime doing that.

GW: Yeah. I mean, I take an even broader historical view, I do Fiore, which is like the early 15th century stuff, and Vadi because it's sort of connected and I just like Vadi. And rapier. And then I kind of skip the 16th century for reasons we don’t need to go into. Rapier, rapier and dagger, that sort of thing, then 18th century stuff, smallsword and sabre. So if you think about it, I've got longsword, big cutty weapon, sabre, shorter cutty weapon. I also do a bit of Messer and falchion and whatnot. Because why not, they’re lovely. And then rapier, long thrusty weapon, smallsword, short thrusty weapon and of course, daggers. Very short thrusty weapon. And all the accompaniments. So weapons in two hands. Sword and buckler, because I do medieval sword and buckler as well, from 1.33, which is like my earliest thing. Sword and buckler, sword and dagger, sword and cape, all that sort of stuff. So I don't even really think of it in these terms. When I look back at it, it's like side arms from 500 years. And what I'm really interested in is how do these different weapon types behave differently? And what context was this weapon developed for? I mean, very obviously, the rapier was developed for a different use than the knightly longsword. They are similar in many ways. But the use case is different and so the weapon is different. And how much is the change in the weapon changing how it's used or the change in the intended use, changing the design of the weapon? And how much of it is simply just fashion? I mean, a lot of it is just fashion. Some bellwether person like the king of France or whatever, decided that he wanted a sword like this, started wearing one, now everybody wants one. I'm not a fan of being restricted to one system. Let's say I was just doing Capoferro, if that was the only thing I was interested in doing. To understand Capoferro properly, I would still have to study what came before, what came after and what was being done at the same time that was different. So I think of it like a cross, you know, you put your target system in the middle. There’s what came before, what came after and what was happening at the same time on either side. Because one book cannot possibly contain all of it.

JY: Yeah, of course. And then there's the fact that the actual author themselves, you might just resonate with the way that somebody writes or describes something better, which is why I buy everything. Like I buy all your books, all everyone else's books, if anybody wants me to read their book.

GW: I'm very happy for you to be reading my books and buying my books, but I don't want you buying anybody else’s, because they might disagree with me. And then you might think I was wrong. Sorry. No.

JY: But to be fair, you've got me to buy other people's books as well. So yes, you mentioned the 1.33 course. Of course I have that too. So the Paul Wagner, Stephen Hand book, which I affectionately called Wagner Hand, I found that book which is very difficult to get, by the way, now. Because you recommended it. So it's like what do I not know? And it's this quest constantly of I need to learn.

GW: And that book, it came out 20 years ago. And at that time, both Stephen and Paul are friends, and I’m not speaking out of turn. Paul’s a lovely guy and Steve’s a good chap too, but that book is really interesting to see what was the state of the art in sword and buckler research 20 years ago and then compare it to what's being done now. Like my Swordsman’s Companion book, which came out a couple of years later. Technically, it's entirely obsolete, but it's still an interesting window into how people were approaching this stuff decades ago.

JY: Yeah. And I think a recurring theme in all of this is someone will write an article about something and go, I've just worked something out, and loads of people, like you said I've been doing this for a very long time, they will say, oh, yeah, we went through that process. We got to a similar place. But the problem is there's been 20 years of conversation, we can't get back to that point to hear it. So it's looking at why was it like that.

GW: My issue with that sort of thing is when people come up with their fantastic new theory, these days there is a kind of due diligence process that people ought to be doing before they start spouting their opinions on things. They should check what has been done before because it's actually really annoying when you publish something and then ten years go by and people are not doing what's called a literature review. Before they start spouting their opinions they are not doing a literature review and figuring out and seeing what's already been done and doesn't need to be repeated, what's already been done but they might disagree with, and they're not actually interacting with the published work that's gone before. I mean, it's fair enough if it's just somebody posted it on Sword Forum 20 years ago, it's not reasonable to trawl through Sword Forum that to find stuff. But if it's been out in a book or article or something like that, I think there's a reasonable expectation of due diligence being done.

JY: So I totally understand where we're coming from. I think Bob has the same attitude. But when I when I come in and I'm like, I've just seen this, that's different, why do we not do it that way? And why was it done that way? So I get to hear that full conversation of what happened, why is that not right, why is that not your current interpretation of this, what did you learn. So I get to relive all of those conversations. So whilst I appreciate it’s probably really frustrating for you, it's super useful for me and my learning.

GW: In which case, I should be less of a grumpy old man.

JY: No, but please rant more publicly. I like that because I learn.

GW: Okay, so I described you in the intro as a provost of the Hotspur school and I'm familiar with the term obviously, but I'm guessing that quite a lot of my listeners will not be. What does it mean generally and what does it mean specifically in the context of the Hotspur school?

JY: I think it's a very traditional term which still gets used in some universities, but I think that comes with some admin jobs. All of the grades, if you like, in our school is based on the fight schools around in Henry VIII’s reign and therefore we use that as a sign to show progress.

GW: The Guild of the Meisters of Defence, you mean.

JY: That's the one. Yes. And so we have exactly the same ranks. You start off as a fellow. Rightly or wrongly, as gendered as that language might be, that's the traditional term. A fellow and then scholar and then and free scholar and then provost. And it's basically your progression of your understanding of what we're learning, application in whatever way, whether that's academic or whether that's, you know, in some sort of sparring situation and for some weapons, that's easier than others. And so our first grade is scholar, which is the rest of the school fence the people taking the grading, essentially, I guess, with longsword and Messer, that are our prime weapons. It's sort of friendly sparring. But the idea is like, are they a danger to either themselves or others? Can they actually at least protect themselves? Can they show control under something that's getting closer to a more stressful situation? Are they able to start to pick techniques and responses under duress? And so we do 40 passes, which is basically until someone says, I've been hit. Something like that with each weapon. But quite often because it's an entire afternoon.

GW: That's quite a lot.

JY: It is. And quite often it goes on quite a lot longer than that. To maybe like 120 passes, I think we've had 180, someone was very, very keen, but it's basically a friendly sparring day. No one has to win, nobody scores, no one has to win. It's not about winning and losing, it's about celebrating what you've learnt. Very, very few people fail and we've had a couple of advisories and it's mostly things like thrusts that are not quite controlled to our liking, to the face. And so yes, we have that and then you're able to pick up and study the other weapons. So we have four other things that you can learn: sword and buckler, poleaxe, dagger and wrestling. So you pick up two of your electives and then when you've passed some sort of assessment with the next two, then you become a free scholar. And then when you sort of know all of them and everything has to improve at every stage, so you'll learn longsword and Messer also has to have improved for you to get to that free scholar place. And then when we've run out of weapons that Bob and the senior students feel like everybody's well versed with, knows enough, knows enough sources, then you are awarded provost.

GW: Was there a test?

JY: No.

GW: Interesting, because George Silver lists these various tests and things. And your first one, the scholar, feels a lot like the sort of testing that George Silver was talking about. Yeah. What's happening after that seems to be more kind of academic and internal. Is that fair?

JY: Sort of, I suppose I sort of found out about the fact that I was being awarded this after a class on a Monday and then it went public. And that's why I haven't really responded yet, because I don’t know what to do with it. This was going to be the next four years of my life. What now? What am I supposed to study? So I need to think about what am I going to do? So yeah, I mean, you know, you're never done with this, but I liked that as a framework. So I picked as my electives, I actually picked Sword and Buckler, which is one of the reasons I signed up for your class. I'm just absorbing as much of that, basically. And poleaxe, because poleaxe is beautiful. I love it so much.

GW: For the listeners who can't see, I just grabbed my poleaxe off the wall and I'm waving at Jo to make her feel at home.

JY: Yeah, love it. It's just the Swiss Army knife. It's all of them. It's all of the weapons. So, yeah, there's a dagger in there. There's an axe. There are two long swords attached together at the pommel.

GW: And a spear.

JY: So I chose those two and then I didn't do dagger because obviously I did lots of dagger at Aikido and although the Tanto is a lot shorter, the techniques are very, very, very similar. And one of the things that really struck me about Fiore’s dagger work particularly, well, all of it. But I think Fiore was the one that was introduced first is like this is aikido, but I've just swapped my hands over, oh yes, because humans have the same pivot points as they've always had. Okay, this makes a lot of sense. So I didn't pick that up as an elective and because it felt like cheating. But then we went to Dijon and there was there was a dagger class. And it was sort of a little bit of sparring. They had to give you attacks and there had to be a little bit sort of resisting. And I just really enjoyed myself. It was so much fun and all of those aikido instincts and I mean, I have done things like that. We were on mats. I haven't trained on mats like that for ages. And I had lots of lots of lovely, lovely training partners. And at one point I think I had somebody in a headlock, so I didn't have the dagger on me. I had this guy, he had a dagger. I'd got behind him and I was choking him out whilst I got mine and stabbing him. At another point some of the instinct came in, somebody had got me sort of bent over, so I did a forward roll. I don't know what happened, but by the time we'd come up on the other side, I had him, I had his dagger. So I jokingly said, can we consider that my prize play and the people that were from the school that were there were like I would back you for that. And then they had a conversation and Bob decided actually, rather than just doing that, he just wanted to award me the provost. So it came from a cheeky ask. So yes, I don't really know what to do with it yet and it feels like a bit of an honour that I think it will take a while to sink in.

GW: Yeah. Does it involve any like teaching responsibilities or anything like that?

JY: Well I've been helping teach for ages, to be honest.

GW: Not specific to the role, like I have provosts in my school in Helsinki. And any branch has a provost and the provost is the person who's responsible for running the branch under my direction, as it were. So when I'm not there, they're in charge. There's an assumption that they've been training for a while or whatever, but fundamentally in my school, it is an administrative rank.

JY: Yes, it is. But before this, Bob gave me the title of Captain, which was again, of course.

GW: Bob obviously likes you very much.

JY: I'm very, very enthusiastic.

GW: Captain Jo York, Provost.

JY: Yeah. In my day job, I do a lot of like coaching and things like that obviously. So and I work in Start-Up World where I've had my own start-ups and then now I coach other start-ups and I run a programme that finishes today actually where I've been working with 15 founders that had very interesting techie ideas, and I've helped them over the last five months, like stress testing that and hopefully give them all of the foundations for those to be very good scalable businesses. So because I've worked in start-ups in these have where I've worn lots of lots of different hats, I can code. I was a graphic designer before anything else. So obviously I got into interface design in like the late nineties. And so I've done sales, marketing, business coaching and I'm used to sort of like building a brand and things like that. So as soon as Bob found out these were skills that I had, he started asking for advice and it's escalated.

GW: You do know that I will be asking you to have a look at what I'm doing and tell me how it can be improved or streamlined.

JY: Please do. I would love that. And yeah, so I have been doing those admin roles a bit. The website is still terrible because I haven't had time. It is much better than it used to be. But we've done things like a beginners’ course which has been really, really successful, sold out pretty much for the last two years. Since we could in lockdown they've been absolutely sold out every single time. And it's meant that we've probably doubled the size of the school over the last couple of years. And all of that is streamlined now. So I have been doing those. So I do things like design the t shirts, buy the t shirts. So people have been coming to me for those roles. And then, of course, if Bob isn't there, then there's sort of a hierarchy of students that would teach the class. So Andy, who's been provost for a couple of years, would do that, and then maybe Ian or myself would come in and teach something. But we've all helped write bits of the beginners course and things like that. I've been doing that for a while, so I guess it's also an acknowledgement of that as well. I just love swords and teaching in schools and finding new people and telling them about swords.

GW: Yeah. There's a little bit of the evangelist in us, I think.

JY: Yeah. Because there's still a part of me that can't believe this is a thing that I'm allowed to do. And if seven year old me knew that adult me found out about this and wasn't throwing everything into this, I'd never have forgiven myself. It's like when you look at the child in you. So the first event that I went to back after lockdown, I was just so happy, just so happy to be surrounded by sword people, learning. I love it. I absolutely love it. I can't get enough of it.

GW: Yeah, it is. It is nice to be with your tribe, isn't it?

JY: Exactly.

GW: Now, you mentioned some of your entrepreneurial stuff and obviously I research my guests before interviewing them because it's the right thing to do and it makes for a better interview. And there's a bunch of stuff on your LinkedIn bio that I don't understand. So I'm going to ask you some questions about that, which feel free to relate it to swords if you like.

JY: I mean, I'll find a way.

GW: Because it’s all swords, really, right? Okay. All right. “Ignite accelerator”. So what you do is you take you take some lighter fluid, you put it on the accelerator pedal and you light it. Ignite accelerator. What is an accelerator exactly?

JY: So think of it as a like a personal development programme, but with a very keen business focus. And so we have two programmes that we run every year and one of them is a pre-accelerator. So that's very, very early stage businesses, usually tech with high scaling potential, and it could be someone that has an idea or they might have built something, but they just need a bit of help turning it into an actual business. And so that's the first one that we do is pre-accelerator. And then later on in the year we do like an accelerator, which is more of a focus on raising investment. Some of our pre-accelerator teams raise investment from investors. But the accelerator is more focussed on that and large raising larger amounts of money.

GW: So and so if I have a tech idea, you're the person I should talk to.

JY: Yes, I'll probably tell you it's rubbish, but.

GW: Okay. Well, why don't I just float a problem?

JY: Brilliant. You've already started well, Guy.

GW: If I float a problem at you, you tell me whether this has potential. One of the biggest issues that people have with creating any kind of IP is handling the money afterwards. Because let's say you and I cooperated on writing a book or producing an online course or something. Then for 70 years after our deaths, we still have to split that money. That’s hard. Okay, so in the book world, for ebooks, there is Draft2Digital, for example, which will allow multiple authors and they will split the money for you. So you put in how much each of you is entitled to and they will split the royalties for you. Which makes life easier, but that's just e-books. So no print and that's just books. So not online courses. I mean, there's a million different kinds of IP you could be producing, pictures and whatnot. So my idea is for a platform where you can collaborate with people and register your IP or your ownership of this IP through this platform. All the money goes into the platform, which is then split up amongst the collaborators. The other thing this allows you to do is, let's say I've written the next Harry Potter or something even better, but because I'm an impoverished author, I can't afford to pay an editor properly or a cover designer properly. So what I could do is say, look, I will pay you this much upfront and this percentage of the royalties from this thing in perpetuity. And so people, I'm thinking in terms of books, obviously it's wider, like graphic designers, layout designers, and all these creative people who are involved who are usually only paid upfront a fixed fee and that's that actually get a piece of the action long term. So if the book does do a Harry Potter, imagine how pissed off you'd be to know you got paid maybe a grand and a half, two grand to do the first Harry Potter book. And that's it. And you get none of the action afterwards. And what this platform would do would be allow creatives to plausibly offer a piece of the action to people who are normally involved in the process but only get an upfront fee normally, like a session fee for a musician. And of course, the money is in the long tail. And it persists 70 years after the death of the copyright owners. So this platform, it would have to have the ability to handle the money, the ability to split the money for a specific project amongst people who have a certain stake in it. So let's say for our project, I own 30%. You own 30%. And the other 40% is split between, say, five other people who were involved, maybe a graphic designer, maybe an editor, maybe a photographer, maybe whoever. The money will get put into their accounts on that platform automatically when, for instance, we make a sale on teachable or we make a sale on whatever platform we're selling on.

JY: Yeah, fantastic idea.

GW: I had this idea five years ago. But the problem is, I'm not a tech start-up person.

JY: Let's build it. Let’s go.

GW: We could build it.

JY: We could. Most very early stage tech is all about founder problem fit. And the reason for that is you need to be really passionate about what you're building and really care about it. And the more inside knowledge you have, if there's any secret sauce to any of this, it's know more about your customers than anybody else. And that's the same for you when you're writing books and content is the same thing, right? Exactly the same thing. And what traditionally happens is people get so in love with their own ideas that they miss all of the feedback of people going, that's not quite what I write. So they build it and then they go, how many do you want? And everyone goes, No. Basically it's applying the scientific method to business and just tech start-ups have got really good at it because there's so many more unknowns. So the analogy that I always give is hairdressers, big fan of hairdressers, my mum's a hairdresser, so I feel like I understand it as a business. But there are certain things we don't need to prove. We know a lot of people have hair. They want it cut, usually with scissors. They want it sort of nearby. And we understand that there's different costs involved. That's a model that's been proven with a tech start-up. People might have hair, they might want it cut. Do they want it blowtorched off? Can I hit it with an axe? And so the only question, though, with the hairdressers is, do you want me to cut your hair? And I can tell you from lockdown, the answer is no, you do not. Nobody wants that.

GW: Oh, can I just say, I have two teenage daughters, both of them get me to cut their hair.

JY: Nice. Skills. What style do you do?

GW: Yes. They have long, straight hair. And every now and then they want it trimmed off straight at the back. That's it.

JY: I'm terrible at it. My mum would be very embarrassed. She's seen my partner's hair and I had to cut it over lockdown and she's like, what have you done? So there's a lot of unknowns basically. So my job really for the pre-accelerator has been I've had 15 teams over the last five months and today weirdly is the last day. And so we did a big showcase on Wednesday and they all had to pitch, they had a three minute pitch to a live audience. And my job is to basically try and give them the foundations to be able to work out whether what they're doing, is it the core business idea? Is it speaking to customers? Is it the marketing? What is it? How do they test? How do they do very small tests to test every hypothesis all the way through that business? I can tell you it's much easier to do it from the outside looking in than it is from the inside of your own start-up. So that's the advantage that I have. And also I've done it three times now, so I've made a lot of my own mistakes and I know the implications of making a decision early on that you might not see where it goes in like year three or four or whatever.

GW: And the thing is, the founding DNA of a company determines so much about what happens next. Like, I think the reason Facebook is a cesspool is because it originally began as a way for dude bros at Harvard to rate the hotness of their female classmates. I mean, how is that not going to turn into something shitty? It has to.

JY: Exactly. So certain things over that five months. So it could be like workshops, but we also have other people like me, they'll have a weekly meeting with the teams and we just coach them. Like, what problems have you got? What solutions do you need? Who do you need to speak to? Do I know someone I can introduce you to that's done that before that you can speak to? So it's all that kind of support around people doing hard things. And then the reason it's a cohort is because they're all going through it together. So now they've got a peer group of people that understand what it's like to try and do impossible things where normal people, normal, sensible people that have safer jobs think they're mad because we all sort of are, right? Entrepreneurs are all sort of a bit mad. And it becomes so much of your own identity if you're not careful that, the success or failure of this company, this thing that you're building, feels like you. And then most start-ups will fail because they're incredibly hard. It's really risky. But your second or third one will probably do much, much better. And it's about building up the person and then helping them separate their ego from that. They're all great people. But we've also done some like how do you hire a diverse workforce and maybe some unconscious like bias that you don't know yourself because culture is such an early part of the business. And particularly if, say, you’re two co-founders, your first hire, that is a third of the business that is now a different person. And so very early on, it can go very wrong very quickly. It's brilliant because I get all sorts of things thrown at me from so just those 15 teams that I've been working with. We've got some metaverse NFT nonsense and they know I call it nonsense, it’s brilliant nonsense. To health tech, to some marketing tech in there. We've got some physical products. There's an insole that goes into shoes that will help people detect - people with diabetes are more prone to ulcers. If they get ulcers.

GW: Yes, they end up with amputations.

JY: Yeah. And amputations often lead to death.

GW: Yeah. Well, they're not they're not happy. And so it’s an insole for diabetics to early detect when the circulation is bad so they can get it before they have to have that. Oh, that is genius.

JY: It's great isn't it, it's really good.

GW: Yeah, the use case is really straight forward and finding the people who need it is a very clearly defined segment of the human population. If you don't have diabetes, it's just not useful to you. If you have certain types of diabetes this is not useful to you. If you have the sort of diabetes which puts your feet at risk of being chopped off, this is something that you want and it's a small expense to stave off a massive downside. As a business, it’s an obvious slam dunk, if it works.

JY: Yeah. Well, so that's always the thing, right? So it's about finding what's the thing that you want to build, who cares about that and do they really care about it? So we talk about this, as you can imagine, there's a whole load of stupid phrases and jargon in start-up world. But one of them is, is it a painkiller or a vitamin? So are you actually solving somebody's pain or is it just you know, it's a nice to have thing and it's finding that that's product market fit in the truest term comes much later but if you can find a problem that people really want to solve, you can find different solutions for that. And that's a business.

GW: But also like one person's painkiller is another person's vitamins. Swords are a great example. The core of the people who pay my rent, not that I rent anymore, but you get the idea. The core of my client base, to talk in business terms, are the people for whom swords are more than a painkiller and they're more than a vitamin. They are oxygen. I'm helping them get access to this thing that they actually need. But for most people in the sword world, for some, it may be a painkiller, but for most of us it's a vitamin. It's a nice to have and they're cool and their fun or whatever. But they come and they go. For those people for whom this is the thing. Those are the only people who I actually feel I have to look after properly.

JY: Perfect. That's exactly the right thing. And that's what I would teach the teams. And there's loads of different models to do that way. There's a really good questionnaire that we used at my last company, Ricochet, and it's an excellent question. And it is how disappointed would you be if this thing that you're paying for would go away?

GW: Right.

JY: And some people are like, okay, I would learn to live again. That's fine. But the people are just like, no, this would be really bad. They're the only people you should focus on first.

GW: I recently read a book called Don't Trust Your Gut, by Seth Something-or-other. I’ll put a link in the show notes. He's a fascinating sort of economist, tech person, data scientist sort of person. His first book was called Everybody Lies in which talks about basically using Google searches as a window into people's honest, true desires and interests. You don't lie to a search engine, but you do lie to psychologists and you do lie to questionnaires, and you do lie to make yourself look good in all sorts of other situations. But, you know, you don't lie to Google because you're looking for the thing you actually want. The second book, Don’t Trust Your Gut, has all sorts of, what he calls counter counterintuitive facts. Like, for instance, there's this story that tech founders, successful tech founders are usually. Yeah, like 19, 20, 21, like Bill Gates and, and Mark Zuckerberg. And they made these billion dollar companies and they started when they were children. But the average age of a successful tech start-up founder is mid-forties. Which, when you think about it, is obviously true. But actually, there's a story that no, they have to be young. And there's also the story of like the maverick outsider who doesn't really know the industry and so they can see it clean and they come up with this genius thing and it's like, amazing. And yeah, every now and then somebody does that, and it works really well. But generally speaking, having, say, 20 years of working in that field makes you much more likely to be a successful founder of a company, because you understand the field, actually, that's an advantage.

JY: Absolutely. Yeah.

GW: It's not a sexy story though.

JY: But there's all sorts of myths, isn't there? We're so fixated with this hero's journey. It's like this one person that goes and does something. Actually, what that one person did was really good at finding other people that were really good at the things that they were.

GW: Right. Are you familiar with the literary trope of the heroine's journey?

JY: No.

GW: Okay. Hero’s journey is as you say, and it's all very well documented and blah, blah, blah. Less well understood, less talked about is the heroine's journey. It's got nothing to do with the sex or gender of the main protagonist. It has everything to do with their strategy?

JY: Interesting.

GW: Well, Harry Potter, for example, heroine's journey, because it's a team of kids who get together and defeat Voldemort. Harry is like the point man, but he’d be dead without Hermione, dead without Ron. Actually it's a team of the three plus there are the helpers and they all develop over time. Like The Fellowship of the Ring. There's only one ring and Frodo does carry it, but it's not a hero's journey, it is a heroine's journey because he is entirely dependent on his team to get him to where he needs to go. And at the end, when he is alone, he fails. And then Gollum comes and bites the ring off and the world is saved. But when he's finally on his own, doing the heroic thing alone, he fails. So it's actually classic heroine's journey stuff.

JY: I will totally check that out.

GW: There are books on it.

JY: Yeah. No, I haven't come across that. I mean, I usually talk about the hero's journey when I'm talking to the teams about storytelling, right? So if you're building a business, you're creating a movement. And so that starts with customers and then it goes into team and then, you know, investors and sometimes investors before team, but you know what I mean, you have to build a movement. And what people mistake with using the hero's story as a framework is they think they're the hero. They're not the hero. The audience is the hero, you have to take them on that particular journey. And so, yes, it’s absolutely fascinating. I mean, whilst we're giving book tips, if anybody has got a start-up idea, and wants to validate something. And there's a really good book called The Mom Test, like mom, it’s American It should be mum, or mam in the northeast I guess. But yeah the mum test. It's basically how to do user interviews but like really well so the premise behind the book is and the author whose name escapes me right now and he had this idea to build an app and he thought his mum was like a perfect archetypal customer for that. And it was all about recipes, I think. And he went and asked her, so I'm thinking about building this. What do you think? And she went, Oh, that's great. It's lovely. Of course I'd buy that. And then he built it. Nobody did. Nobody used it.

GW: Because your mum will buy whatever you make.

JY: Exactly. So how do you ask questions to get to the truth so that even your mum won't lie to you to make you feel good about yourself? So the mum test is really, really good. And it's just a really good way of getting to the truth of what is the real problem here. And the other one is like looking through the framework. It's called Jobs to be Done, and there's loads of books on it, but it's basically what is the job that the thing that you're doing is actually trying to solve? What is the job that people would pay somebody for? So in your case with yours, you would maybe pay a broker for that, right?

GW: Or an accountant or somebody. Somebody who would take the money and hand it out like this.

JY: Yeah, exactly. So it's like looking at it through those particular lenses and focussing on the problem, not falling in love with the solution. So the other phrase that I want to use here is quite often there are products as solutions looking for problems. And you end up building something that people quite fancy or like it's not built for anybody, doesn't solve anybody's problem. It sort of looks at a collection of people's problems and you really need to focus on that. You can widen your audience every single stage, so in your case, with your books and courses, it's people that somebody that wants to study sword and buckler. So you start there and then you widen out the weapons or you widen out a specific thing. You don't just go, I'm going to teach you HEMA. It needs to be specific. You're solving a specific problem. And for a lot of courses, it's like it's a beginner's course because you get them in and then you teach and then you know what they know. And then you can build, you can upsell like this is more advanced. You don't just go, I'm going to teach any human, any weapon. And that's the problem that people make with the fact that they get too wide, too quick. So, again, very easy to spot from the outside, easier to spot from the outside. Really difficult when you're doing it yourself.

GW: Yeah. And they the royalty split thing, it was because I was talking to a friend of mine who's written some books and needs to pay for graphic design and editing and doesn't have the money to pay for it up front. And you can't reasonably ask an editor who you don't know to edit your book in the hopes of future royalties. That's just mad. No sensible editor would take that unless they were your mum.

JY: Unless she's lying to you.

GW: Well yeah, but having some way to hedge it so you pay less upfront, like Alec Guinness in Star Wars. When he was hired for Star Wars, they couldn't afford to pay him his usual rate because they had no money then, it was the first Star Wars. And so he got a piece of the action.

JY: Wow. That was a good deal.

GW: That little piece of the action, if I remember the story right, made him more money than all of his other work put together.

JY: Yeah, I'm not surprised. I mean, makes sense, right?

GW: Yeah. I have a basic principle that I won't do significant amounts of work for any company that I don’t own a chunk of. Because why would I? If I'm putting work into something I want that work to be an investment in future growth rather than just something that's put on to the void.

JY: Yeah. Makes total sense. And I think this is this idea as well about paying it forward. Like, there's plenty of people that have helped me upfront on my journey and it's about if I can help somebody, that's great. But you can't help everybody for free, in order for me to be available to help other people, I have to get paid in some way to do that. And when you take a gamble, it's because you believe in something. Exactly why very early stage angel investors, so high net worth individuals investing their own money, why they tend to be the first people in taking the most risk, but they get a larger percentage of the whole thing because they've taken that risk. It's because they believe in something. I really believe in paying it forward, and doing small tests. So speaking of tests and things like that, one of the things I did last year was I did a little experiment called a cutting square, you know, Meyer’s square. I made an interactive version of it and it's cuttingsquare.com.

GW: Okay. I’ll put it in the show notes.

JY: I’ll put it in the chat. And it was just, I want to build this. I think it'd be interesting for people in the school. And I wanted something to get my teeth into. And again, after we sold Ricochet, my last start-up and, and I thought, well, maybe if people.

GW: Fuck, that's brilliant.

JY: Thanks. And so there is a way to contact me on that. And then at some point when I get some time, I will try and make those improvements. But there’s left handed, right handed, you can set the tempo. It's not perfect. It's very hacked together as a minimum viable test.

GW: If this is your idea of hacking something together. I think you’ll do all right. So basically, what it's doing is it's colouring one square off, and you're supposed to cut into that square, cut into that square. So whichever square it gives you next, that's where you throw your blow.

JY: So I will at some point make it so it can be used offline on a phone, which is the biggest request that I get. But yeah. Anyway, it's up there for people to try. I was amazed that it didn't exist already. I was like, why is nobody done this? Please, everybody enjoy. Feedback.

GW: Yeah. I will make a note to put that into the newsletter as well.

JY: Oh thank you. Thank you.

GW: Because this solo training thing. It's something of an obsession of mine. I've got my solo training course, my last non workbooky book but was basically the principles of solo training, modesty entitled The Windsor Method. Because that's what my friends told me to call it. If you can't train alone, then you are entirely dependent on finding suitable nutcases to train with. And that's really difficult, sometimes.

JY: It's highly inconvenient. Nobody wants to train as much as I do.

GW: Right. And also there's a whole bunch of training that is better done on your own. You can't hit things full force if that other thing is a person. Certainly not with a sword, anyway.

JY: Definitely not with an axe.

GW: No, definitely not. Do you really need somebody else that when you're doing your strength training and your push-ups and whatnot?

JY: It's not really a spectator sport, is it? I suppose it is, CrossFit.

GW: But actually I do have my morning train-alongs, which is not a spectator sport, it's just me doing my training basically. But really it's just presented as a class so that students will show up so that I actually have to show up and do it.

JY: Peer pressure works really well if you use it for good rather than evil. It's really good.

GW: It’s not really peer pressure is more professional pride. It's like, I’ve said I'll run this class at this time in this place, I'm going to have to do that. That's why, incidentally, back in the old days when I was going to these events, WMAW and ISMAC and whatnot. They will always have me in the first thing Sunday morning slot. Because they knew that if I was teaching the next morning, I wouldn't get too drunk the night before. I would get to bed early and I would actually be fit to teach a class the next morning. And there weren’t that many other instructors who well, pretty much none of them are professionals, so understandable, who they could rely on for that. So I got stuck with it. And after about ten years of this, I said to the organisers, I have done my time. I will not teach on Sunday at all. Take it or leave it. And they were like, well, fair enough, Guy. So yeah, fair enough. And so I was done teaching by Saturday afternoon and I could get drunk with my friends Saturday night and I'd be a bit groggy the next morning and it was fine. But yeah, it's that sort of, you know professional standards. I do want to ask you, what is your favourite episode of the show? This show?

JY: Right. I did think about it. I did think about this. And I think this question is a lot like asking which is the best dog? Like they're all good dogs. They're all good dogs. So I'm going to answer a different question, because there's too many to choose from. What I really like is that you don't know what you don't know, and the shows are full of those little nuggets of things. It's like, Oh, that's really interesting. If I can apply it to fencing, then it gets a million more points than anything else. But sometimes it's just a way that somebody explains something that just makes it click. So the question that I'm going to answer, if that's okay, is the most listened to episode is actually the one with you and Cornelius just completely geeking out about tempo.

GW: So you have listened to it more than once?

JY: Yes, I was listening to it in the car. And because you're also discussing sources that I don't know anything about with weapons, I don't do. Honestly, you would cry if you saw me with a rapier.

GW: I would cry with joy.

JY: You wouldn’t. The By the Sword event that Fran puts on. A couple of months ago, they have like a mixed steel and they sort of like roll the dice. And we do I think it was longsword, sabre, which I basically treat like a Messer and rapier and I'm terrible with the rapier, really, really bad. So I basically did Fiore’s sword in one hand.

GW: Okay. That's not quite. Although Capoferro says at the end at the end of his book, Il Gran Simulacro, he gives you a secure way to defend yourself against all sorts of blows. And he says to wait in a low quarte. And when they attack, beat it up with a prima and then thrust, which is very similar to what Fiore is doing with the sword in one hand, only the sword is pointing forward rather than back at the beginning. So I think you probably were actually channelling Capoferro through that.

JY: I will take that from you, Guy. I'll take that.

GW: And so the Cornelius episode is the most listened to?

JY: Yes. I was listening to it in the car, which I usually do. And I had to pause it because I'm like, I need to write notes on this. So I use the system for all of my notes called Roam Research. It's basically like a personal knowledge system. There are other things out there as well. But this is this is the one I use. And it's basically something you can just poor your thoughts into, written thoughts and it will link it together. And the difference is you don't have to have a series of documents that you file away. You can put tags around it. So I used to have my own wiki for things and because I have to keep track of yes, I use this for sword stuff, but just for, you know, all of these different things going on with business like marketing, raising money. I've got all of these different resources for the teams that's how I manage it. I manage everything in there. So I was like, I need to write this down on and I’m missing it.

GW: Roam research?

JY: I'll send it to you in an email, I'll send you that. But yeah, it's really good for writing papers as well, apparently. And yes, I was like, I need to stop, I'm not concentrating on the driving here. And I feel like I was missing things. So, yeah, I had to stop it and go on to something else, something more frivolous, and then come back to it. So I think I've probably listened to that one about three times. I write lots of lots of notes on, so I hold all of this amazing wealth of knowledge that everybody brings in from loads of people that I like already know and respect. And then I meet a whole load of other ones on this. And they're all excellent episodes. I enjoy them all. That's my get out answer.

GW: That's actually a really good answer, because just the thing is, taking risks is the wrong way to put it, but I don't have a consistent yardstick by which I decide whether somebody should come on the show or not. It's more an instinctive, ha that person seems like they would have something a bit different to offer. I mean, like getting Christian Tobler on the show. That's an obvious person to have on because he's been at the forefront of the historical martial arts movement for the last 25 years. Obvious candidate. Jessica Finley, another fairly obvious candidate. But finding people who may have only been training for six months or a year, but they're doing something interesting with it, like documenting it on YouTube, for instance. It's difficult for me to know whether somebody is going to be a good guest. And I have absolutely no way of predicting how it's going to be received because some of my some of my, shall we say, quirkier, nichier, less obviously mainstream historical martial arts, popular people have generated the most “oh, my God. That was amazing,” emails from listeners. And some of the obvious heavier hitters have had less obvious effects in terms of feedback that I received on the show. Cornelius was a popular one. But that wasn't the standard episode. I didn't actually interview him. He emailed me with a question about tempo, and I said, look, we should probably discuss this over Zoom or something because it would be more efficient. Oh, why don't I record it? I didn't even introduce him properly, but I need to get him back on and actually do a proper interview.

JY: Yeah, he's great. I trained with him, so in the before times the event at the Royal Armouries, I was there for that and I trained in his class. I really enjoyed it. It was a very much back to basics, like his basics. But I think this is where, when you've studied martial arts for a really long time, you start to really appreciate the nuance. So I will often stop somebody even when I'm training, or I'll pull over the instructor. You did that different, can you do that on me so I can feel what the difference is and I'll try and get them to describe it. And it might work for me, it might not, but the fact that it's different and new, I'm like, why are you doing it like that? Like, there's a reason. Do you find it works here? But I try and unpick it. And that's why I buy as much as I can and try and absorb it because you don't know what you don't know. It's really good, I enjoy it a lot.

GW: And that goes to the diversity thing you were talking about with choosing the people to work with in start-ups. Because if all of you have computer science degrees from Princeton then there may be diversity of other things, but there isn't going to be a diversity of education. So you're going to be missing certain things that you don't know you're missing.

JY: Yeah, exactly. And quite often, I think we're slowly becoming more aware about the importance of diversity in all sorts of sorts of different ways. One of the ones that seems to get missed is like we touched on it, like age because it feels like a very much a young person thing. You need somebody to do a job. You want the best person to do that. Who is the best person to do that? Somebody that's been doing it their entire life. And then you start to bring in different perspectives about how you don't know that you are accidentally alienating people with your product, it's that wealth. And I think we're better as humans when we work together. And that needs to include as many people as possible and diverse opinions and as long as they're not offensive. And I am aware offensive is in the eye of the beholder. But long as you're trying to be a good human, trying to be good to other humans. I feel that sort of diversity that's how we've done amazing things as a as a mammal. Like, why would we then want to pigeonhole that?

GW: Yeah. I mean, team building is the original force multiplier. Two people together can do much more than two people separately. I had people installing solar power into my house two days ago. And the electrician who is doing tricky electricians stuff I know nothing about. And he called one of his colleagues who came and helped for a couple of hours and it basically shaved about 4 hours off the total time, even if you include like the man hours, the extra man hours of having an extra person there for 2 hours. It shaved hours off the job because doing it together was so much faster than doing it on his own. And it's true for all sorts of things. The first step in any campaign is recruit allies.

JY: Yeah, totally. And sometimes it can be the smallest amount of commitment. Just go and find somebody that's done that before and just go and talk to them. Find three. Because there’s opinion and there’s fact. But like what happened when you did this? What did you learn? And just get that insight. And that gives you a massive head start as well. But being able to tap into those different networks and get as much information as possible like yeah, and that works as well in the fencing school. So one of the really nice things that we've been able to do as we grow, when we get into free fencing and things like that, we all feed back to each other because as we all get better and I’ve started to encourage people to film themselves and look back so that they can start to develop this part of the brain that what just happened and they're sort of like, yeah, but then they might beat me. Yeah. Then you'll have to find a new way to beat them and then we all get better.

GW: Exactly. Exactly. Fencing memory is a skill that can be trained.

JY: A really important one.

GW: Because if you don’t know what just happened you can't fix it for next time. Okay, now I have a couple of questions, as you know, as a listener to the show. What is the best idea you haven’t acted on?

JY: Um, this was really difficult for me because I really do act on stuff. And so the thing that I haven't acted on yet is I've been thinking about putting out my content of the stuff that we've been thinking about in the school. And the reason that I haven't done it is because I'm trying to work out the way to frame that. So people realise this is a constant work in progress. I'm not saying I've done this and this is done. So there's that imposter syndrome of I'm not saying this is the way I'm saying here's some stuff that's interesting. What do you think? And the other reason is I don't want to have to deal with unhelpful opinions from the Internet. Constructive feedback is great and I don't care how direct that is, but just people just being awful humans because they are sat at the other end of the keyboard. So I need to find a balance for that. So when I find a balance, I will start to do stuff.

GW: Yeah, I have a pretty clear set of principles. Firstly, I don't do social media at all. I pay somebody to do it for me. So when you see something of mine posted on social media, it's not me doing it myself. It's somebody else who I am paying to do it because they don't have skin in the game. And sometimes people say nasty things about some of the things I do, and that's just part of it. And they're not offensive to the person I'm paying because it's not aimed at them. One nasty comment completely derails your day. When it comes to things like book reviews, if my target readers are telling me this is exactly what they wanted and giving me five stars or whatever then I know the book is good. Then if I get a one star or two star review, I know I have sold a book to the wrong person. It is a marketing problem. Maybe I should have been clearer in the blurb, like somebody bought one of my workbooks which clearly states it has space for writing notes and whatnot. And it gave it a one star review because it's got all those blank space in, but it's a fucking workbook. You fucking bellend, was my emotional response. Really, what that was is the blurb needed to be clearer. This is a workbook. It is not dense text.

JY: Sorry, that's my dog being really excited.

GW: Your doorbell just went. New people! New people! Ruff ruff.

JY: I bought the workbook and because again, you don't know what you don't know. But bearing in mind one of my sort of things here is like, how do we get more people involved in this? People make the mistake of calling them basics. They're not basics. They're fundamental. The fundamentals, you cannot understand too much the fundamentals. And I will read everything. And the way that people explain it and like, you know, that's really useful. But sometimes just like it was in the Cornelius episode, just the way that somebody else explains their understanding of a principle, just go, oh, it sounds really obvious now you said it like that, and I feel like an idiot, like it just really helps, right? And then sometimes you’ll be trying to explain that to somebody else in the class or something like that. You've got that to rely on. This mental model.

GW: Okay. As a tech person, what do you think of the workbook format with the QR codes linking to videos and stuff? Does that work?

JY: I very excitedly told Bob that it had arrived and that there were so many good ideas that we needed to be heavily inspired by. So for years QR codes appeared everywhere. And I think that lockdown was the time of QR codes. And some of the issue with technology is timing. And like there's nothing really new into this and we just tweak it a bit, right? And we just find a different ways to solve that problem. I thought that was brilliant. I thought was really, really good.

GW: So it works?

JY: Yeah. And I have tried it. I think it's great and I'm very dyslexic and so any, anything where I don't have to type a URL is great. Having said that, my phone is actually quite good at reading text now and translating. That's incredible. That's a thing. And so yeah, I really liked it.

GW: Okay, good. Because I for some reason the workbook format that I created, started with the rapier one hasn't really taken off. I'm not seeing anybody else doing it and pretty much nobody is buying it. It's like my regular books outsell the workbooks ten to one.