Episode 157 Sword People are Book People, with Diniz Cabreira

Share

You can also support the show at Patreon.com/TheSwordGuy Patrons get access to the episode transcriptions as they are produced, the opportunity to suggest questions for upcoming guests, and even some outtakes from the interviews. Join us!

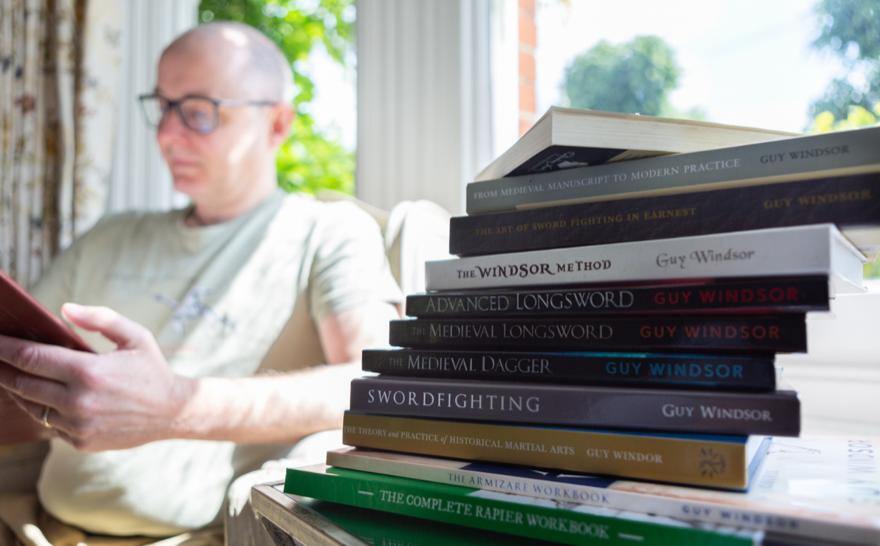

Diniz Cabreira is a Kunst des Fechtens practitioner at Arte do Combate, a publisher of historical martial arts books, primarily on La Verdadera Destreza in Portuguese, at AGEA Editora, and a graphic designer. He’s currently researching historical martial arts publishing and has a lot of questions for Guy...

This is a great episode for anyone interested in book publishing (not just sword books) as Guy shares his wealth of experience in publishing and selling tens of thousands of books over the last twenty years or so. Find out what sells and what doesn’t, what might be the next big thing, and how to get your own book onto people’s shelves.

Transcript

Guy Windsor: Diniz Cabreira is a Kunst des Fechtens practitioner at Arte do Combate, a publisher of historical martial arts books, primarily on La Verdadera Destreza in Portuguese, at AGEA Editora, and a graphic designer. He’s currently researching historical martial arts publishing, and has a lot of questions for me... So without further ado, Diniz, welcome to the show.

Diniz Cabreira: Hi, Guy. It's a pleasure to be here.

Guy Windsor: It's nice to meet you. In the pre-interview chat, you said that we have met once in person, which was many, many years ago, so it's nice to kind of face to face again. So I ask everyone on the show whereabouts they are. So why don't we start with that? Whereabouts in the world are you?

Diniz Cabreira: Okay. I am in Santiago de Compostela, which means some people know because of the way of St. James, the medieval people.

Guy Windsor: I have a friend who did the Santiago de Compostela pilgrimage last year, and she wrote a book about it, which I've just read. So it is top of mind.

Diniz Cabreira: Well, it's an experience. It's a nice experience for people who are interested in history. It's, I think, maybe a way of connecting with that history.

Guy Windsor: Have you done it yourself?

Diniz Cabreira: Yes. Yes, I have. Not the long one from Roncesvalles or something like that, but maybe two weeks walking or something like that.

Guy Windsor: So a couple hundred kilometres maybe?

Diniz Cabreira: No, no, no, no. More than that. Maybe 300, I think.

Guy Windsor: Okay. Wow. That's quite a long walk.

Diniz Cabreira: Yeah. But it's fun. It's great fun.

Guy Windsor: And I imagine there's lots of other people doing it at the same time.

Diniz Cabreira: Yes. It's very nice to do it with people you know, because that's an experience. But it is also very interesting to do it alone because there are other pilgrims on the way. You cross them and there is this kind of connection because you're all sharing the same experience, but at the same time you don’t really know them. It's interesting. I mean, like HEMA, going to a HEMA event.

Guy Windsor: And if you live in Santiago de Compostela, then presumably for you the experience of arriving there would be quite different from someone who's never been there before.

Diniz Cabreira: Yeah, but of course, it's getting home instead of getting to your destination. Half the trip, because you're going to get back.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. Huh? Actually, you just sent me off in another direction. I had an idea in my head of what we're going to talk about this morning. And you just sent me off on this sidetrack. All right. I will bring us back to topic. Okay. So how did you get into historical martial arts?

Diniz Cabreira: The blame is on my parents. Of course. It's always because of your parents. My father used to tell me the stories of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table and all this kind of stuff. So that was always like a background romantic stuff going in my head. And I like history because of that, too. I'd been practising Eastern martial arts. Judo initially and Aikido later, but at some point, I had finished my university studies and I didn't have the same schedules, so I couldn't continue practising Aikido. So I went looking for something and there was this group of people my age. We were very young back then and they were trying to set up a historical fencing group and I said, okay, this seems interesting. Let's go take a look. And I joined them and it really was interesting. And it's been 15 years since.

Guy Windsor: Wow. Okay. Arte do Combate. So you’ve been with the same group, your entire historical martial arts career?

Diniz Cabreira: Yeah, well, we needed to change the name and reorganise a couple of times, but it's essentially the same project, or at least for me, because I am currently the longest running person in that project. It's the same thing.

Guy Windsor: Actually. Okay. And you got into publishing how? It takes quite a lot of energy and some money and a lot of, shall we say, desire to do it to actually publish a book. So what made you decide actually, do you know what, let’s publish a book?

Diniz Cabreira: I was doing HEMA already at the time, and I was working as a graphic designer. And I have always loved the physical aspect of design, you know, designing for paper as opposed to designing for the web or things like this. And so I was actually working in the world of professional publishing already. And when we began researching the kind of treatises that existed in the Iberian Peninsula and which time those were and these kinds of things, we realised that many of them weren't really available. At the time, what was most better known were the Italian and German schools of medieval fencing and maybe even some of the French stuff and some of the English stuff. But what was going on in the Iberian Peninsula nobody knew. So I met Manuel Valle Ortiz, which maybe some of the listeners of the podcast will know. He's a medical doctor, but he has always had an interest in history and in fencing and he was already researching the Iberian treatises and he has written a very extensive bibliography, about 500 pages, documenting all the known books on the matter. So I met him and I already knew some Ton Puey from Colonia, from Academia de Espada, and it was like a group of people who met who have these very different sets of skills. I knew how to layout books. I was working in the publishing industry. So I was like the technical side of things. Manuel had all the theory. Ton had a lot of experience with practice. Diego Conde Eguileta, we began to create this work group and say, okay, let's get these books that nobody knows about, because they were in public libraries, but nobody was paying attention to them, and we republished them. We didn't have to spend a lot of money because we did most of the work. I did the layouts, the design and this kind of thing. I could afford the better prices because I was in the business.

Guy Windsor: Right. When I'm producing a book, one of the biggest expenses is layout and cover design, because I know enough about graphic design to know that I need a professional do it properly. It is never a good idea to design your own covers unless it happens to also be your job. Now, the reason we decided to get on this call is because you sent me an email saying you're doing some research on a historical martial arts publishing generally, and you sent me this very, very long questionnaire. I looked at it and I was like, to answer those questions properly, I'm going to have to spend hours typing, and that doesn't seem like a sensible use of time. So why don't we get on a phone call or even an Internet call and do it verbally and then send you the recording and get the information that you need and not have to spend half a day typing. So, what can I do for you?

Diniz Cabreira: Okay. It makes a lot of sense to do it this way. So let's get on with it. Okay. The idea, for some context for the listeners, the idea is that, well, we all know that books are very important in HEMA because, I mean, that's where it comes from, right?

Guy Windsor: Yeah. It is what makes it historical. The ‘H’ in historical martial arts is we get this from books. Yeah.

Diniz Cabreira: Yeah, that's the idea. So there is this special relationship with books and it actually has a long tradition. I mean, people like Paulus Hector Mair. In their way, they were already gathering old techniques and republishing them. So this is nothing new, but let's say that we are living maybe, in some kind of historical a martial arts renaissance. I think so. In this context, there are several people who have been publishing their work. There are a few, not many, but four or five publishing houses which are specialised in this topic. Well, I do have a professional interest in knowing how publishing works for small scale projects or businesses, and I also have this interest in HEMA and how it is developing in the present. So I say, okay, let's take a look at what we are doing with book publishing now. With the idea of publishing old treatises or maybe new interpretations of these old treatises in the present and what are the difficulties that people face and what tools maybe we have available. And also to open a discussion, because the idea is to turn this into a paper, to present it at this year’s Dijon HEMA event and maybe also carry a bit of a roundtable there, perhaps because other publishers will be there too. So it’s kind of a professional, semi-professional, endeavour to know better what we are doing. So the kind of questions I am asking is well of course for people to, to first identify the project. What is it that they are doing. I am calling it ‘project’ because some people are like a personal publisher, they are publishing themselves, self-publishers. Some of us are associations or clubs, not strictly businesses in the in the monetary gain sense. Some people are professionals or at least they semi-professional, trying to make part of their living out of that. So it's like a broad scope and so, maybe this is obvious, you are Guy Windsor, so we already know what you do and what you publish. What would you say your focus is on publishing books?

Guy Windsor: Okay. I don't think of it in those terms. I do the work that I do, and I find out almost by accident that I have a book that needs publishing or a course that needs publishing. I don't necessarily distinguish between one thing and the other. I mean, for example, last year I produced a course on how to teach historical martial arts. I thought that was going to be a book and I tried to write it as a book and it didn't work. And then I produced a course and it worked really well. And now with the transcriptions from the course all tidied up and everything, I have actually like 90% of a book. So it's probably going to be a book as well. But I mean, the book publishing side of things represents, depending on the year, somewhere between 40 and 60% of my income. So it is a major part of what keeps a roof over my children's heads. So I take it extremely seriously in that regard. But also, I publish stuff as the wind takes me. I'm not terribly focussed and strategic about that. So, for example, I realised I needed to print out the Getty manuscript. Because I wanted a paper copy that I could scribble on and do stuff with. And I looked at the cost of taking it to a local print shop to get it printed out, and it was going to cost me about 50 quid. I thought, hang on this is a bit stupid. This is a lot of money just for a bunch of loose bits of paper in a shitty plastic comb binder. So I thought, well, hang on, I have all of the infrastructure for publishing books, so why don't I send these files my layout designer, get her to lay it out as a book and produce a cover for it, and then produce it as a reasonably priced facsimile that is literally two thirds of the price of getting it printed out in your local print shop and put in a shitty binder and you get a nice shiny hardback that is priced at the point where you can throw it in a fencing bag, you can scribble all over it, you know, if you want to, you can cut pieces out and paste them in other places. I mean, you can do anything you want to it, because it is priced that way. Which is in marked contrast to Michael Chidester’s absolutely gorgeous leather bound, hand-stitched, glorious reproduction of bliss and awesomeness. And so my facsimile is aimed at throwing in fencing bags. Michael's facsimile is aimed at preserving and reproducing the source in the most accurate way possible so that if an earthquake hits the Getty Museum, being where it is, that's not unlikely. And the Getty manuscript is swallowed into the bowels of the earth, never to be seen again. Then at least we have these fantastically high quality reproductions. I mean, he goes to the point of reproducing the collation of the manuscript. In case listeners don't know what that means. This is the way the manuscript is originally stitched together. The number of leaves folded over and put inside each other and then stitched into a stack of these quires, or signatures, as they're called, which is the manuscript itself. He has reproduced the way it stitched together, which is something that nobody will ever see unless they rip the book apart. Mine is not produced that way at all. It's printed on demand and the pages are kind of glued together in the modern fashion. And as a work of art, it is not even close to what Michael's is, but it's aimed at any practitioner of Fiore’s art can get a good quality printed copy of the manuscript without any interference with people fiddling about putting translations in. It is the cheapest way to get the closest you can get to just sitting with the original manuscript and flicking through it as if you owned it.

Diniz Cabreira: They cover different needs, I suppose.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, absolutely. And bless Michael for doing what he's doing, right? I buy everything he produces, whether I can afford it or not because one has to support this kind of artistic lunacy because it is majestic. But his goals are a little different.

Diniz Cabreira: And that makes sense. That is one of the things that I want to explore because at present I think there is such a need for HEMA books that all of the authors and publishers and such publishers that doing this. We are not really competing with each other, we are complementing each other. We are trying to cover a vastly huge area.

Guy Windsor: Exactly. So maybe to kind of put it in context, I should take you through the publication of my books before self-publishing, why I went into self-publishing. Why I started doing it myself and where I am now. Would that be useful? I wrote my first book starting in about 1999, 2000, and this was long before the whole sort of the machinery of publishing books became available to the non-professional. And so I sent it off to a publisher in the States called Chivalry Bookshelf, and they published it and it sold really well. And they did a second print, and it was published in the traditional sense where they ordered a print run and then they distributed that print run to various places. And it went well enough that my second book, The Duellist’s Companion, I sent that to them and they published in the same way. Let me be really specific. Some years later, there was a court case in which eight of the authors that had been published by this company sued that company for non-payment of royalties. And the result of this was that I got the copyright to my books back and no money. But also I was required to sign a non-defamation clause, which means I have to be very careful what I say about these people who published my book and never actually paid me any money. So I have to stick to the facts very carefully. Okay. So at that point, I had already submitted my next book. Actually no, my second book came out in 2006. My first child was born in 2007. My second child was born in 2008. I wasn't doing a lot of writing at the time, and I think in 2009 I produced The Little Book of Push Ups, which I put through Lulu, because that was the first print on demand aimed at consumer level writers as opposed to publishing houses. And I also had it printed locally and hand sold it in my salle and sent copies out to people or whatever. And then I was writing the replacement volume for The Swordsman’s Companion, my first book, which, for people who are relatively new to historical martial arts, 25 years ago, we knew practically nothing and this book, The Swordsman’s Companion in 2004, was intended to give people a way of starting historical martial arts, starting longsword stuff, even though we didn't really know what we were doing. So by 2008, 2009, I was literally eight years of full time teaching and full time historical martial arts instruction. And so I'd done a lot more work on Fiore, and I had a much better idea of Fiore’s system as opposed to general longsword. And so I wrote the book that became The Medieval Dagger and The Medieval Longsword. It was originally one book, and I sent it to the publisher, Freelance Academy Press, started by Greg Mele, Christian Tobler, Tom Leone. Somebody else was involved too, but I’ve forgotten. And they recommended splitting out the dagger stuff. So I adjusted it so that there was The Medieval Dagger, followed by The Medieval Longsword and they were incredibly slow getting The Medieval Dagger out and they were even slower with The Medieval Longsword. So while I was waiting for them to publish The Medieval Longsword, I also did my first Vadi translation of Veni Vadi Vici, and I had the copyright back for The Swordsman’s Companion and The Duellist’s Companion. So I thought, well, I'll just self-publish these. Why not? So I did a bit of research. And of course, I had a company in Finland, which was like the business side of my work life. This was before you could get a full individual level account at Lightning Source, which was the print on demand side of the Ingram publishing empire. So I had a commercial account with them and I found a graphic designer re-laid out, put the new covers on The Swordsman’s Companion and The Duellist’s Companion and I published those. And then I did a crowdfunding campaign for what became Veni Vadi Vici, the translation of Vadi that I did that wasn't very good. It has been pulled since and massively improved. And so by the time I'd been waiting two years from sending in the finished manuscript and all the photographs, by the time I'd waited two years for Freelance Academy Press to publish in the The Medieval Longsword, I had already published three books myself. Literally, in the time that they failed to publish one, I had published three and I thought, fuck this, this is ridiculous. So I took the book back from them and published that myself. I did a crowdfunding campaign to raise the funds to publish it, and that went really well. That was in 2014. So The Medieval Longsword came out in 2014. And at that point I had, under my own roof as it were, I had The Swordsman’s Companion, The Duellist’s Companion, Veni Vadi Vici. Then The Medieval Longsword, so that’s four books and just The Swordsman’s Companion by itself made me about $10,000 in the first year I published it myself. So I was like, hang on, this is much better for me than getting somebody else to publish it. What does the publisher do right? They hire a layout person and they hire an editor and they hire a cover designer and they edit the book and put it together and they put it into various print distribution systems. I can do that myself and actually make a significant income. Remember, historical martial arts are my profession. All of my income, all of it, comes from historical martial arts related activity, like teaching classes, writing books, producing online courses and so on. So by 2014, I really didn't have any interest in getting some other company to do what I could do perfectly well myself with some paid help. And then I have control over the book. So, you know, if I want to do a rebrand, change the cover up, change the blurb, try an advertising campaign, all that sort of stuff. I can do that without having to argue with the so-called publisher.

Diniz Cabreira: I think that that makes total sense. And I think many others have discovered that.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. And the thing is, to my mind, there is absolutely a role for publishers, particularly in the historical martial arts space. Particularly, for example, for authors who have a day job and historical martial arts are their interest and their hobby, and they've written a book. I mean, a classic example would be, for example, Dierk Hagedorn. He's got a day job, right? And he produces these stunning books. He's also a graphic designer, so he has a hand in the layout, but it doesn't make sense really for him to go through the hassle of publishing it himself if there's a professional publisher who will do it for him. Also, if you're a career academic and you get your income from getting the next academic job like a professorship or lectureship or whatever. Your books only count if they're published by the right kind of publisher. My books would not count in that regard because they're not produced by an academic publisher. So if you're publishing for career purposes, you need to go through a publisher. And if you are publishing as a hobby and you don't need to make any money out of the book, then it makes sense to go through a publisher. But if you are trying to make a living in the historical martial arts space, I think it makes a lot more sense to do it yourself.

Diniz Cabreira: Or even if you have the skills, because not everyone has maybe the same kind of skill set or ability like you may have.

Guy Windsor: But I didn't have those skill sets.

Diniz Cabreira: But maybe you have the ability to learn them.

Guy Windsor: No, because my primary skill set is hiring good people. But again, I didn't find my graphic designer who does my layouts. I asked friends and a friend of mine knew someone and so I hired them and likewise with like the actual process of publishing. Once you have the print files and the e-book files and the cover files, it is just admin work, it’s grunt work. It takes a lot more skill to market a book than it does to publish a book. I taught my assistant how to publish a book in a morning. Once you've got the files you need to upload it to here and you need to put this metadata in there and that metadata in there and that blurb in there and you know, there are plenty of people with that skill set. So that can be hired out as well. The real difficulty comes is selling the book, not in actually getting it from I have the files now I need to put it into production.

Diniz Cabreira: We do have a section of the questions which are related to sales. Maybe this is a good point to tackle them.

Guy Windsor: Okay.

Diniz Cabreira: So the hardest bit is selling the book? How do you do it? How do you go about it?

Guy Windsor: Before I answer that specifically, I should highlight that I got into this space very early. My first book sold really well without me doing anything. Okay. And this is largely because there wasn't any other book on the subject. And so I have benefited from getting in very early, which is something that someone coming into the space now can't do. So anyone listening who is thinking about doing this, you can't reproduce the early part of what made it relatively easy for me. But the key things for selling a book: it needs to be professional. It needs to look professional. Professional cover, a professional interior, or at least professional looking interior. It needs to be indistinguishable from a commercially published project. Once you have that, you have a professional looking product and it's in the system, I would highly recommend making it as wide as possible so people can stumble across it on whatever platform they like buying books on. There are exclusive options you can go with, like for example, Amazon's Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Direct. I never do that because my goal in publishing is to make it as wide as possible so that anyone can find it. Then you have to find out where the people are who want to read your book, or who are likely to want to read your book. And you have to go to where the people are. Which back in the day was Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, places like that. The problem I have with the whole social media marketing thing is that social media and my brain do not get on very well. And I have massive ethical problems with the business model behind Facebook, Twitter and so on. So the received wisdom, which has been true for at least 100 years, is the money is in the list. What that means is your income will come from the people on your mailing list. Back in the old days, that was paper mailing. These days it's emailing, but the money is in the list. In other words, you need to start a mailing list and you need to get people onto your mailing list who you can then tell about what you're producing. Now people don't want to join a mailing list generally just to be told what to go and buy. There needs to be a bit more to it than that and there are lots of really good resources out there for how to start and run a mailing list. Probably the best is a book called Newsletter Ninja. But the best overall information on how to market a book is a book by Joanna Penn, who incidentally is the friend of mine who did that pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. She wrote a book called How to Market a Book and it's fantastic. It is maybe a little dated. Some of the specifics may or may not have may not still be workable. I mean, it is always the case when you're talking about anything on the Internet, like this company you recommend today is gone tomorrow. But the principles that she recommends have been basically how I have made a living since I read that book in about 2015. So, I mean, basically what it boils down to is content marketing, which is you produce stuff that people like for free, people who want more free stuff exchange their email address for the free stuff. So they are now on your mailing list. And now they are on your mailing list you give them more free stuff. And you talk to them and you're nice to them and whatever. And then when you have something that you want them to go buy, you tell them about it and they go off and buy it. Now, to my mind, the gold standard in that kind of marketing, I know I'm doing my job properly in that regard when, let's say I’ve produced an online course and I send an email out to my list saying, “Go buy this course,” I get people emailing me back to say thank you for letting me know, because the essence of marketing, really, is tell people about things they want to know about. Imagine your favourite band was coming to Santiago de Compostela and they were going to be playing a gig and you didn't hear about it, but the lead singer dropped you an email the week before and said, “Diniz, we're doing a gig in Santiago. You've got to come. Here is 20% off the ticket price. Go!” You wouldn't be like, “Who the fuck is this bloke telling me to go to this bloody concert?” You be like, “Oh my God, that's fantastic. I'm so glad I didn’t miss it.” Right? That's what ethical marketing is really about. It's not persuading people to buy something they don't need, it is letting people know that the thing that they want is available.

Diniz Cabreira: And maybe making it noticeable over the noise, the background noise of everything. And we get ads for lots of stuff.

Guy Windsor: And this is also where a newsletter works really well because social media platforms are inundated with ads. Now, I do use ads on Facebook because they work, which is annoying, and I have to kind of hold my nose every time I pay Facebook, like give fucking Zuckerberg more of my money. But the thing is, there are a lot of people who are on Facebook or whatever who aren't yet in my ecosystem. And because of the way Facebook works these days and paid ads to reach those people, to rescue them from Facebook and get them into my ecosystem, which is much nicer. I mean, the fundamental trick of marketing is being heard, and the best way to be heard is to produce quality content that people like and share. But not that kind of, you know, “like and subscribe”, “click that button down below,” none of that shit, but just if you write something that is valuable to people, some people will eventually find it and then they will go, that's so cool. I will share it and they share it with their friends.

Diniz Cabreira: It's producing the real stuff, real content.

Guy Windsor: For content marketing, good content is useful on its own. You don't give them half of an exercise and they have to pay for the second half. You give them all of the exercise and then say, if you like that exercise, which is strengthening your quads or whatever, then you might like this set of exercises, which is our complete leg program.

Diniz Cabreira: There is more of this. Yeah.

Guy Windsor: Exactly. Exactly. Like, you know, I did a translation of Fiore’s longsword material, which I produced as a book, called From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice. About 80% of that book is available for free on my blog, in the kind of second draft level, shall we say. So it's got the transcription, translation, my commentary and a link to a video for people to go and do it. Most of it, so all of the sword in one hand, guards and blows, and the zogho largo section, all those three sections, all of that content is up on my blog and it's free and people can go and do whatever they like with it, it is theirs. I didn’t get around to publishing the stretto section on my blog because I had it already quite quickly and I was like, oh, hang on, I'm ready to do the book now. So I just produced the book. So each one of those sections, so sword in one hand, mechanics, guards and blows, zogho largo, zogho stretto, each one of those is available as a separate e-book on Amazon, but it's all available together as From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice, the Longsword Techniques of Fiore dei Liberi as hardback, paperback, and e-book. Because people will happily support authors who are producing stuff that they like. It doesn't have to be novelty. It doesn't have to be. Well, I will tell you the translations, the first half of a sentence but if you want the second half you have to pay. It's like, here is the stuff is free, but if you want it in a convenient form, go buy this book. Or if you want it in a convenient form, go buy this course.

Diniz Cabreira: Or a nice one. Well, at least I do. And I know many people who buy books just to have them there.

Guy Windsor: Absolutely. And nothing wrong with that. I know one guy who every time I bring out a book, he buys two copies in hardback, one to keep pristine and one to read. Bless you Sven, you are my kind of reader.

Diniz Cabreira: OK, so that has been very thorough. And very interesting. I loved hearing your thoughts on particularly how to market a book, because I am already getting feedback from some others for this survey and I know that many just put the book out there in whatever platform they are using. It is available, but if people don't know about it, it gets to very few people.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. I think one thing I've tried is going on people's podcasts and talking about my books and stuff and that can work, but honestly the content marketing approach is probably the most effective for non-fiction and even for fiction. You know, I know plenty of fiction authors who have one book that's in a series, they write in series, the first book is free, free and widely distributed so people can get it and they read it and they like it, they get to the back of the book and it's like, oh, I want the second volume, oh, I can get it for free off the author's website. They go to the author’s website, they download the book for free. That puts them on the author’s mailing list, and then they go buy volumes three, four, five, six, seven. So the first two volumes are effectively free. And again, that's a good model if you write in series and it's a good model if you have all of that extra material. But if you just have the one book, I mean, one thing I've done is like from my Theory and Practice of Historical Martial Arts book, I had a chunky like 80 page, the first 80 pages of the book, and it didn't finish in the middle of the page, it finished at the end of a chapter, right? Because I’m not a dickhead. Some people do do that. That free sample was so that people could read it and go, this is absolutely my kind of book and I can see the table of contents and go, yes, I want to know about these other things as well. And then they go and buy the book, because you can have like a free sample. That helps to sell books too.

Diniz Cabreira: Okay, those are interesting ideas. I'm sure people will love to hear about them. You mentioned eBooks.

Guy Windsor: Yeah.

Diniz Cabreira: Um, let's talk a bit about them. So do you have a numbers or maybe a rough estimate of your readers, whether they prefer more the paperback version or digital versions?

Guy Windsor: Most of my readers clearly prefer to read on paper. But, the e-book is really important for several reasons. The e-book serves many purposes. Firstly, most importantly, if somebody can't afford to pay for the book, I will happily send them the eBooks for free. Because I can send the e-book for free without it costing me money to print and ship it, so I can distribute it at any price point, including free. Realistically, I simply can't do that with the printed book. Secondly, some people do prefer to read e-books. And they like their Kindle, their Kobo, their iPad, their TV screen. It is really not down to me to tell readers in what format they should want to read my book. So I think that every book should be available as an e-book. And if it isn't there something wrong, something has gone wrong because the information in the book, if it's worth the effort of publishing it, it should be published in every reasonable format, which is also why I'm in the process of producing audiobooks. I've got an audiobook of Theory and Practice. I'm working on an audiobook of, I'm also doing a rebrand for The Windsor Method because absolutely nobody bought The Windsor Method: The Principles of Solo Training. And so I’m rebranding it, new title, new cover and making the audiobook as well. And hopefully that will do a bit better. But the critical thing with eBooks is they are just so easy to distribute. And here's the thing. People worry about piracy, right? Let me just knock down the head right now. Obscurity is a problem, piracy is not. Because the most pirated books are the most popular. And actually Neil Gaiman did this experiment where his book was released in Russia. And he took a PDF of the book and released it himself on a pirate site. And a whole bunch of people downloaded it. About 80,000 people downloaded it. Sales of the actual book in Russia went through the roof. Because the sort of person who will download your book for free and read it for free on a pirate website, firstly is not your customer anyway. Secondly, might become your customer if they can see the content. And so when they pirate the book, they read the book they go, oh my God, this is amazing, love the book. And then they go buy up hardback perhaps. Or maybe they just don't have any money. But in three years’ time when they get a decent job, they're go oh my God, these books, I'm going to go and buy them. And you know, this author has brought out a new book. I'll go buy that one. I mean, when I notice piracy, I do fire off a legalistic email and put it down, but that is only for one reason, which is you have to protect your copyright to maintain your copyright. So if somebody can demonstrate that I have copyright on something and I'm not protecting that copyright, then it basically makes it possible for people to do all sorts of other things with my content, which I may not approve of. So yeah, so I think eBooks are really important. But also are you familiar with the concept of price anchoring. I produce all of my books in e-book, paperback and in hardback. Primarily because the hardbacks don't sell very much, but they're very profitable. You make a lot more money on a hardback than on the paperback. The e-book is the cheap end, the hardback is the expensive and the paperback is in the middle. So if it's ten for an e-book, 25 for paperback or 45 for the hardback. So the hardback that makes the paperback looks cheap. If it was just paperback and e-book together, the paperback would make the e-book cheap and the e-book would make the paperback expensive. And both of that is bad.

Diniz Cabreira: That makes sense. Yeah.

Guy Windsor: So producing it in all three formats is maybe one reason why most of my book money comes from paperback sales. That's because price anchoring works.

Diniz Cabreira: Okay. Okay. That's interesting. When you produce the eBooks, do you use like an automated conversion from the layout of the paperbacks or the hardbacks or do you lay it out especially?

Guy Windsor: Okay, here's what I do. Most of my books are laid out by a professional book designer called Bek Pickard. Bek sends me the interior print files and the e-book in epub, PDF and Kindle format. How she produces that is her business, frankly. Literally, I pay her and she sends me these files and that's that. But also for books that don't require sophisticated layout, I use a program called Vellum, which automatically produces the interior print files at whatever size you want and eBooks and in whatever format you want. And it is so clever that if you format the links correctly in the back of the book. So like to your other books, what it exports for Amazon it is all Amazon links in the back. When it exports for Apple books or whatever they call them, they keep changing the names, it's all Apple Book links in the back. For Barnes and Noble as well. So wherever the customer buys the e-book, the links in the back to go and buy all the other e-books is on the same platform, which is genius. I've moved away from that altogether anyway, because what I do now is I am most interested in getting people on to my own store to buy direct from me, for two reasons. Firstly, I make a lot more money from each sale. And secondly, if they come and they buy it from me, then they end up on my mailing list and I can maintain that relationship and then hopefully they'll go and buy more of my stuff in the future. So I was very careful about making sure that the links in the back of Amazon books were all Amazon links, but now, no. I haven’t processed my back catalogue for this yet but all of my links will be to my store so people can come and buy my books from me because it's better for me.

Diniz Cabreira: Okay, so a question which kind of overlaps with the next one, when you sell the eBooks, you mentioned that you use PDF, you also produce them for the iPad, for the Kindle, like specific formats for each of the different platforms. Well of course the proprietary ones like Amazon, they manage their own stuff on the rights management. For things like PDF, which I know that you already sell, you just make the files available for a price and people buy them. They can download it and that’s it.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. It’s a bit more sophisticated. I use a company called BookFunnel where I upload an epub and a PDF and they handle the sideloading onto customers’ devices. So you buy the e-book in all formats from me. You get a link to the BookFunnel page and you tell BookFunnel what formats you want and it sends them to you. And if you have any difficulty getting them onto your device or whatever, BookFunnel professionals will help you with the tech side of things. I used to just sell the files directly and there's nothing wrong with doing that. These days, when you buy an e-book from me directly, you get sent the BookFunnel link, which gives you all the formats and any tech support you need to get it onto the device the way you want it.

Diniz Cabreira: That's great.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. Because every device is a different size. There's a million different little technical things that could go wrong. So it's much better that we have professionals handling that. So yeah, BookFunnel for the win.

Diniz Cabreira: For the paper books, for the physical books, you say that you are funnelling people to your own shop, to get the books from you. But do you handle the printing and the shipping of the books directly?

Guy Windsor: Oh God, no. I have a life. I have better things to do than pack and ship books. Now, back in the old days, you had to do a print run and then you pack and ship the books. And that is a nightmare because to get a decent price on your books you have to be printing maybe 500 or a thousand or 2000, 5000. And that's a lot of books taking up a lot of space in your house, right? And then you have to pack and ship each book as the order comes in and it is a giant pain. So in the beginning I was just using Lightning Source. That is a print on demand printer where let's say you go to buy my book on Amazon or order in a bookstore or wherever, the signal goes to the printer, the printer takes the money and prints and ships the book and then sends me some of the money 90 days later. Later on, Kindle started doing print books as well. And it's worth doing paperbacks through Kindle because Amazon will prioritise, in their nasty little algorithms, books that they are getting more money from and they get more money off the book if it's a Kindle file or if it's printed by them and shipped by them. So they will, if you have a paperback or hardback or whatever with them and or through Lightning Source, you are more likely to be visible on Amazon if it's printed by Amazon. So all of my books are also printed on KDP, Amazon's publishing side of things. Kindle Direct Publishing, is what it stands for. I've been selling e-books directly since about 2012. I used Selz to start with. In 2016, I shifted to Gumroad. Last year I shifted to Shopify. And the reason for that is simple. A company in the UK called BookVault, they created an integration. They are a print on demand company. They created an integration with Shopify, which means that people can go onto my Shopify store at swordschool.shop and they can buy a paperback or a hardback and that signal goes to BookVault. BookVault print and ship the book and off it goes. The great thing about that is Shopify take the money and they give me the money. All of it. I have to pay the printer. But I keep a certain amount of money, £25 or £50 or something on my account at the printers, which is enough to cover at least a few orders. And then I keep topping up my account at the printers as necessary, but the money for the printing is going to me first and then to the printers. Whereas with Ingram Spark, which is the new version of Lightning Source, it goes to the printers. They hold it for 90 days and then send it to me. On Amazon, it goes to KDP and they hold it for 30 or 60 days, I forget which, and then they send it to me. Through Shopify the money comes to me and then I send the required amount to the printer. And the difference that makes, fundamentally, is you can afford to advertise. Because the problem with advertising, let's say you're doing an ad campaign on Facebook, and let’s say it starts to do really well and you're getting loads of sales, but you have to wait 90 days to get the money from those sales. That means that you don't have the money to put into more ads. You can't afford to up your advertising budget because the money hasn't come in yet. And by the time that money has come in, the Zeitgeist for that ad has gone. Last year I was running Facebook ads for my Medieval Longsword book on my Shopify store in January, February. And really it broke even because I paid a professional to do the ads for me and I'm paying for shipping, and a chunk of the money goes to pay the postage and shipping if it's the physical book is being bought and so on. So basically it broke even. But I could have kept that going forever because the money to pay for the ads goes out later than the money comes in from the books. So the cash flow is just much, much more positive with the Shopify/BookVault integration than it ever was with things like Ingram Spark, Lightning Source or KDP.

Diniz Cabreira: Although you are also working with a team, which means you keep them on your workflow for future projects, I suppose.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. There's one freelancer who is on retainer. That's my assistant, Katie. She does the podcast transcriptions, podcast uploading. Basically, I needed her when I started the podcast. We didn't actually start working together until the podcast had been going for six months, and then suddenly the whole podcasting got a lot easier, because she's very good at keeping everything organised, keeping everything straight, making sure the right thing is uploaded to the right platform at the right time, all that sort of stuff. I am rubbish at that. She also schedules my newsletter because she's much better at that sort of thing than I am. Then I have my graphic designer for layout. I have a separate person for covers now. I have a separate person for Facebook ads, but they’re freelancers and when I have a project for them, then I ask them to do it. So they’re not on retainer. I don't have any full time staff except me.

Diniz Cabreira: I don't think that in these times it makes a lot of sense unless you are running a really large operation. And for the kind of activity you're describing, this is smart and it seems to work well.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. And honestly, it feels more ethical because my freelancers, I hope I’m a good customer, you know, I pay them on time. When the bill comes in, I pay it straight away. I don't argue with them about how much I should be paying them. And I’ve been working with Bek, my interior layout designer off and on for over a decade now. So clearly she's happy to keep working with me.

Diniz Cabreira: Okay. You mentioned earlier that if someone wasn't able to afford your paperback, you would gladly send them an eBook. Let's talk about prices. So how do you set the price for a book?

Guy Windsor: Okay. On Amazon, you don't have much choice. Because on Amazon, an e-book that is priced between 2.99 and 9.99, you get 70% of the royalties on. 70% royalty on. Under 2.99 or over 9.99, and those prices haven't changed in a decade, you get 35%. So in other words, if I charge £15 for an e-book on Amazon, I would make less money than charging 9.99. It is insane. So on Amazon, I charge the maximum on most of my books, frankly, because they are a lot of work, it is a niche product. And honestly, it's worth it. I'm not producing a novel a month and trying to entertain people for 2 hours. I'm producing high level non-fiction research, developed, worked on stuff that a small market really wants. And so I price as high as I can on Amazon. I have higher prices in my own store and on Kobo because honestly, 9.99 for that much work is a joke. Paperbacks are somewhere around the £25, €25 mark. You have to set in a particular currency, whatever platform you're on, and the way that it converts the local currency is a little bit different every time.

Diniz Cabreira: Like magic.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. So the thing about paperbacks is they need to actually have a good margin on them. And when I was selling the paperbacks through, as I still am through Amazon integrated with KDP, or through whatever other bookseller integrated with Ingram Spark. I'm not getting anything like all the money. So let's say £25 is the sale price. Amazon will take maybe ten and the printing will be maybe five. And so 90 days later I'll get maybe £10. It’s actually less than that. On Shopify, my own store, I make significantly more per book. But it is much more expensive to get people on to the Shopify store in the first place. Advertising costs and that kind of stuff, right? So the cost of sales is higher on Shopify or selling direct. So I keep the price about the same. So the margins are much, much better. But more of that margin is going towards actually getting somebody onto that website. Hardbacks are fantastic because they don't cost that much more to produce, but you can sell them for a lot more. And I am shameless about my hardbacks being expensive because that's what they're supposed to be. The hardbacks are there so the people who really want to support my work and can afford to do so can pay much more for the same book. And they get the shiny hardback and that's lovely.

Diniz Cabreira: There are cheaper options.

Guy Windsor: Exactly. There are cheaper options if people need it. Yeah, including email me and I'll send you any book you like for free.

Diniz Cabreira: Okay. That's great. So just to make it clear, you don't set the price of the book based on the book itself, but more on how the market defines prices for that kind of product.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. I mean, one way to set a price, if you look at the production costs and you add a margin, say 100% of production cost, you double that or whatever, and that's your price. That is the stupidest way to price anything that the world has ever come up with. It makes no sense at all. A book is worth what someone wants to pay for it. I mean, my 1610 Capoferro, I can get that information for free on the internet, but I paid more for that than I did for a car because it's worth it to me to have that physical object in my house and I fucking love it. It is a fantastic thing and I'm not sorry at all. So the value of the book to the reader is, I mean, when you think of books generally, a book that really helps you with a problem or a book that gives you six months or a year of stuff to do in your favourite hobby or whatever. That's worth an awful lot more than the cost of the paperback. With paperbacks, I try to price the value, but honestly, all books suffer from a price anchoring problem in that when you think paperback, most people think mass produced fiction titles at say 8.99 paperback, because that is printed in China in print runs of 10,000 or 20,000 or whatever. The unit cost to the publisher is about 50p, it’s insane. But a specialist non-fiction, like for example an academic book. Usually, an academic publisher could easily be £60 or £70. But generally speaking, those are only bought by institutions. So the book market is massively anchored down. Which is why I can charge $300 for an online course that has the same content as one of my books that the paperback would be literally a 10th of the price, because the courses are anchored much higher. It has nothing to do with the cost of production and has nothing to do with how long it takes to produce. I mean, I could produce a course in a week and I could produce a book in a year. So that's not strictly fair because like my Medieval Longsword course, was based on my Medieval Longsword book. And that Medieval Longsword book took me ten years of research and two years of writing. So actually, the course has like a dozen years of work put into it. It's just that it takes a long time to type out a book. It takes a lot less time to shoot some videos.

Diniz Cabreira: The more projects you develop, I guess, the more they feed back into one another. So it is hard to say how much work went into something. But I know what you mean.

Guy Windsor: The production of course is significantly easier and cheaper than the production for the book but you can sell a course for a lot more than you can sell a book for.

Diniz Cabreira: That's interesting.

Guy Windsor: And that's just to do with anchoring. It’s nothing to do with value. It has to do with what people are willing to pay. And again, I like having my courses priced nice and high because I make lots of money, which means I can afford to give them away for free to anyone who can't afford them. I give away hundreds of courses every year to people who contact me saying, I'm really, really interested in this course, but I can't afford it. So I go OK here you go, or tell me how much you can afford to pay and I'll give you a discount coupon for that amount. Because, no amount of me saying, well no, it's a $500 course, you’ve got to pay $500. No amount of that is going to make somebody who doesn't have $500, give me $500 for a course that fundamentally is not going to feed their children. We’re in the luxuries and unnecessaries market here. It'd be absurd and unethical to demand high prices. I ask high prices, and if people can't afford to pay them, they could pay much whatever they want.

Diniz Cabreira: It makes total sense to me. I have always defended those kinds of attitudes, like the one for eBooks, for instance. I think that the more people that get to your product, typically, the better it is for you in the long run. If you produce just one instance of whatever, a book, then you really have to make that work. But if you are developing an audience, what you want is for that audience is to be as big as possible. Okay. One question that that we left behind. You did mention that the first book that you self-published, you did it through a Kickstarter campaign to raise the money.

Guy Windsor: It was Indiegogo, it was a crowdfunding campaign, it wasn’t Kickstarter. Same difference. But the reason I used Indiegogo was because in 2012, I think it was when I did this for the first time, the only crowdfunding platform that you could use if you were registered as a company in Finland, was Indiegogo. Kickstarter had not expanded to Europe yet. You had to be in the US or the UK to use Kickstarter at that point. Otherwise I probably would have used Kickstarter. But I've done everything, every crowdfunding campaign I've done since I've been on Indiegogo, because the first one was on Indiegogo and it went fine and it works just fine and no reason to change.

Diniz Cabreira: The question was, you did use crowdfunding for that first book. Do you do it regularly for your later books or do you think it is an interesting way to sell a book? Maybe have people pre-order it not necessarily through Kickstarter or Indiegogo through a platform, or maybe even your own mailing list or your own shop. Do you have people pre-order the books?

Guy Windsor: Yes, absolutely. So a proper crowdfunding campaign is a lot of work. It takes a lot of planning, a lot of marketing, and it has all sorts of expenses associated with it that you don't necessarily see. Well, for example, the platform takes 10% off the top and then there's transaction fees, another 5%. So 15% has evaporated before you even see it. And that is a lot of money. So there are costs associated with it that are over and above the time it takes to prepare the campaign properly. And it does take preparation to do well. Okay. So there's that. Routinely these days, when I finish a book, I put the hardback on pre-order and people can pre-order the hardback, get the current draft in its basic form as a PDF. So they can look at that one straightaway. When the book comes out, I go into the back end of the print on demand service and I have their books printed and shipped and it works pretty well. It doesn't raise nearly as much money as doing a crowdfunding campaign, but it doesn't take me as much time and it doesn't have all those absurd additional expenses associated with it. So I would make more money if I did it through a proper crowdfunding campaign. But I make enough money to cover the basically my freelancer costs, layout, cover design, that kind of stuff. I make enough money to cover all of those costs plus something over which sort of helps me see the book through to being published. I would only start a crowdfunding campaign or pre-sell when the book is actually written. So basically when it's out of my head, and it’s off to the professionals to turn from whatever format I've written and into something that could be printed and shipped. I don't want the pressure of having sold a book I haven't written yet. That's a good way for authors to go mad.

Diniz Cabreira: That doesn't seem like a good idea.

Guy Windsor: Although that is how the industry works. Most books in the commercial publishing industry, you sell the book proposal, then you write the book. So you've been paid to write the book. Which is too much pressure.

Diniz Cabreira: Then you get these books and series which never end or never get finished. Okay, so you say that some form of pre-order is a really relevant part of your publishing cycle, to finance the physical production of the book.

Guy Windsor: Yes. And I've also done it for I mean, I produced an audio book of George Silver’s Paradoxes of Defence and I had two professional narrators, one doing the original pronunciation, one doing the modern pronunciation, and that was a lot of money and it was very speculative and it’s way outside what I normally do and so I thought I had better crowdfund that to make sure I can actually pay these people. And I did the same for my card game because again, I had no experience producing a card game. So the game design was basically finished, the basic artwork concept was done and we had the artwork for three or four cards, maybe four or five. We had the game mechanics. You could play the game already and we had the artwork concepts done. So basically what we were raising money to do was produce the artwork and get these decks printed and shipped. And we raised so much money we also did a couple of expansion packs and two extra characters.

Diniz Cabreira: I remember that.

Guy Windsor: Right. But that needed to be crowdfunded. And so I knew we'd need about 20,000 to produce the first two decks. And so I set the if we don't reach 20,000, the decks don't get made because there's no way I could afford to put that kind of money into a game that wasn't going to sell. So, for that kind of speculative project where if I don't have the market for it, I can't produce it. That's where the formal crowdfunding is super useful, right? Because if you don't reach your target, you don't have to make the thing right. But with books where it's basically my effort, most of the work is me doing it, I'm writing a book at the moment that if ten people buy it, I'll be surprised. But I don’t care. I'd like to produce that book that ten people might buy. And it doesn't matter because it's simple enough I can lay it out myself so I don't have to worry about that cost. I can get a cover on it for a few hundred quid. I'm writing the book because I need to learn the thing that's in the book. And so, there's no risk. The risk is just my time and I’d spend my time doing this anyway. Where I need professionals to do most of the actual heavy lifting, that's where I would depend on a crowdfunding campaign to make sure that there's a market there that will actually pay these professionals for me, because I'm not sitting on shitloads of cash to spend on idle projects.

Diniz Cabreira: I didn't pursue that line of thought you just mentioned. But you said at the beginning when we were talking about the focus of your work, why you do the books you do. And I think that is something that we are going to see when we have all the answers of the survey together. I think it is not a surprise. Most of the people who are publishing books in HEMA today. They are doing it because they need that book. They need to work with that books. The actual publication of the book and making it available to others, it's almost like a side effect of the work.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. The reason I wrote The Duellist’s Companion is because I was getting very serious about getting a proper interpretation of an Italian rapier source done. And I picked Capoferro. I thought, right, okay, I need to, I need to create a proper syllabus for Capoferro. So I thought, well, I’ll just write the book then So I wrote the book to basically structure my research and present my findings. And the fact that a whole bunch of people found it really useful and learned rapier from it is just a bonus.

Diniz Cabreira: Yeah, I can understand that. We have talked about how you announce your books and how you talk to your audience. Let's you one move on from sales then, about the books you have produced because you make them as you need them rather than as you think people may need them. I suppose that you will have huge disparities in how well they are received or how many people need them. You have bestsellers, I suppose?

Guy Windsor: Absolutely. Yeah. My absolute runaway, probably 40% of my total book sales and I've got about a dozen books, is The Medieval Longsword.

Diniz Cabreira: Makes sense.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. And the rest is relatively evenly divided. I mean The Duellist’s Companion has done really well, but my workbooks don't do very well, for some reason. They should do really well because if I say so myself, they are a fucking brilliant idea. But I don't think the market is really ready for it yet. They haven't quite got their head around it. Are you familiar with the workbooks I'm talking about?

Diniz Cabreira: I think so.

Guy Windsor: Basically the thing that makes them different is they're sized so they are easy to write in. They are formatted for left handers and right handers so the place for taking notes is on the left side or the right side and every drill has a video clip associated with it with a QR code printed in the book. So you can point your smartphone at the page and it will take you straight to the video. And that basically means that firstly, I can update the video at any time and the QR code will automatically link to the correct video because the link goes on my website and can be redirected anywhere. For the rapier ones it was organised pretty much the way I would teach rapier from the ground up. For the Armizare one, volume two is supposed to come out this year, but I have lost a bit of steam on it. It's actually organised so that you can go through the book in a variety of orders and find the organisation of the information that works for you the best. Plus it’s got these QR codes and stuff like that. Honestly, it hasn't taken off. I mean you would think that the workbook would outsell the training manual by 10 to 1 but it’s the other way around.

Diniz Cabreira: Do you have an idea of why?

Guy Windsor: Honestly I think people are used to buying books. And they're not used to buying workbooks. Same with audiobooks, right? My Theory and Practice audiobook that came out, I want to say, in 2021. I paid a professional to narrate it. I think it has now sold just about enough copies that I've got that money back. It's just about broke even, which is absurd. Because it should do really well, because it's theory, right? It’s me basically describing the architecture underneath all the stuff that we do. It's perfect for audio because it doesn't require any kind of visual aids and you can listen to it while you're driving the car or doing laundry or cooking dinner for your kids or whatever. It should do really well. But it hasn't. It has just gone nowhere. I'm still producing an audiobook, I'm going into the studio next week to read The Principles of Solo Training, because I think audiobooks are the right thing to do and I think the market will probably catch up eventually. When it does, I'll have three or four audiobooks out. Yay!

Diniz Cabreira: You’re ready for that. That’s smart.

Guy Windsor: But also it's a question of diversity, right? People have different disabilities and one disability is bad eyesight. When you're teaching sword fighting, teaching blind people to swordfight is a lot more challenging than teaching blind people to sing, but still, I don't see why being blind should prevent someone having an interest in historical martial arts. If I have audiobooks for them that don't depend in any way on visual aids, then at least they can take part. At least I have that for them, but I haven't got any plans to do an audiobook of The Medieval Longsword because it depends so heavily on pictures. But, you know, eventually I would imagine all of my books will be in audio format of one sort or another, basically because it's the right thing to do. The problem is it is expensive to produce. So I can't just produce all of them just because it's the right thing to do. I have to get people buying my audiobooks first. And then when at least a few of them are making some money, then I can afford to make the less popular or less obviously audiobook suited books. I can make those into audiobooks and it doesn't really matter if I don’t make so much money because there are not many blind people doing historical martial arts.

Diniz Cabreira: So I agree that it is the right thing to do for accessibility. But you also mentioned the very frequent use cases. We all live a busy life, so maybe we need to do the cooking or, or maybe we need to work, like laying out books for someone else. But you can listen to a large amount of stuff when you are laying out a book, I can tell you. So many of us are listening to lots of stuff. So yeah, I think there will be a growing market for that in the future.

Guy Windsor: You would think that the podcast would sell audiobooks, but it doesn't. The podcast doesn't seem to be helpful for marketing purposes at all.

Diniz Cabreira: That’s weird, no?

Guy Windsor: It is weird. You'd expect it to actually move the needle a lot more than it does. But again, I didn't produce the podcast as a marketing effort. The podcast is a diversity play, right? It's a position statement and it is a way of getting people who are less represented in historical martial arts to be more represented. It is doing that just fine. So I don't mind so much that it's not even covering its costs yet after nearly three years.

Diniz Cabreira: That's interesting, I would have thought that it would have helped.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, and again, it's early days, right? There's 150 episodes out and we are close to 100,000 downloads as measured by the podcast app thing, which is not a very accurate measurement, is probably out by at least 10%. But it's making some people very happy and it's definitely improving the visibility of certain minorities in historical martial arts. So it is worth doing for its own sake. Plus, it's fun. Although I must say, it is seriously getting in the way of me writing books. Oh, my God.

Diniz Cabreira: Is it?

Guy Windsor: Yeah, absolutely. It takes up so much time and I have limited time and energy. I haven't taken a single book from first idea to published since the podcast came out. All the books I’ve published since the podcast came out were conceived of before the podcast was invented.

Diniz Cabreira: That’s a bit worrying, isn’t it?

Guy Windsor: Not really. I mean, I've got loads of books out already. I'm not desperately concerned about the next one. There were four years between The Duellist’s Companion and The Medieval Dagger when I had two children. And so in that respect, the podcast is sort of like a child. But it's also a body of work in its own right. And there's no reason to suppose that it won't eventually actually start selling books and basically upping my profile interesting ways. And it will probably at some point if I keep doing it for long enough, at some point it is likely to start financially reimbursing the money and time I’ve put into it. And it is a useful resource by itself. So just as a book is a useful resource, a catalogue of 150, and it's probably going to go on to the several hundreds of these interviews. It is a body of work that is of use to the community. So I can't regret not getting, you know, Longsword IV out.

Diniz Cabreira: Okay. Yeah. Well, the idea that I am getting or maybe it is the idea that I am projecting is that, well, time is finite. There are so many things to do. And I really like the podcast project because as I told you, I like listening to podcasts when I work, or audiobooks or whatever.

Guy Windsor: Do you listen to this podcast when you work?

Diniz Cabreira: Yes, of course.

Guy Windsor: Oh really? Fantastic!

Diniz Cabreira: Yeah, I was going to say there is not that much audio your content for HEMA, but that is not true. There are actually a few.

Guy Windsor: There's quite a few these days.

Diniz Cabreira: There used not to be, but there is quite a lot and if you can count to that videos. Like, for example, Matt Easton, I mean his videos are videos, but they are basically like monologues. There are a lot of things you can listen to. I listen to a lot of sword stuff when I work or do my course or whatever. So I am happy that you are producing these kind of things, and other people, but I am a bit concerned also that maybe there are other projects that are not getting the attention they might.

Guy Windsor: That is always true. No matter what projects you are making because you're spending time doing that, you're not spending time doing something else. That is always true. And I don't even think about it really. Like, you know, the time I spend in my workshop making a piece of furniture like that cabinet over there. This is time I did not spend writing. But honestly, my brain only has so much writing in it at any given time, on any given day. So if I spent the morning on the computer, it's a good idea to go spend the afternoon making things with my hands. I only have a certain amount of any particular kind of activity in me. It’s like lifting weights. You can lift weights for a certain period, and then you have to stop and go do something else. And the same is true of writing, editing, doing anything creative.

Diniz Cabreira: I think maybe given the way you seem to work, if you have the need to write a book, you will do it.

Guy Windsor: It’s Saturday today and at 7:00 this morning, I was writing a book. So, you know, when I get gripped by a book, then yes, it just gets done and other things get left undone. And that's okay because the book has gripped me and has decided that this is what has to come out now.

Diniz Cabreira: Also, I am taking the chance to say that I think you know I have been following your adventures in historical martial arts and sword stuff for some years already and the one thing that I have found very valuable, very interesting is how you are so very transparent about everything. The processes, even the money. I think that's really nice because it helps people. It inspires.

Guy Windsor: Thank you. I think it is necessary, because if I'm teaching somebody some sort of longsword technique they need to know or they need to be able to check where it's coming from. Because otherwise, I don't want my students taking things on trust. Guy says do this, so they do it. That doesn't create the right kind of teacher student relationship, I think.

Diniz Cabreira: Yeah, I would agree. So I just wanted to, to take the chance to say it. Okay. So on the matter of numbers of money, I know that, because I think you told me already, but can you maybe guess how many books have you sold in your career?

Guy Windsor: Like total, total? That a really difficult question because there's. There's the first and second print runs of The Swordsman’s Companion. The first and second print runs of The Duellist’s Companion, I think that went to two print runs. So that must be at least 8000 books there.

Diniz Cabreira: Okay. That’s a lot.

Guy Windsor: Then going back over the last ten years or so, there are so many different books in so many different formats on so many different platforms. It would take an accounting miracle to figure it out. I mean, I think Medieval Longsword must have sold at least at least 6000 copies by now, by itself. So the rest put together must have sold at least another five or 6000 or I guess. I do have all this information somewhere. But the data sheets I get from Lightning Source or from Ingram Spark and from KDP, now from BookVault. And then there's all the eBooks on all the different platforms. I would guess maybe 30,000 books in total. Something like that.

Diniz Cabreira: Okay. But that's enough of a rough estimate because, what we are talking here is somewhere in the early tens of thousands.

Guy Windsor: I would say that.

Diniz Cabreira: That will be a stark contrast with some other projects I know. So it is interesting to know.

Guy Windsor: In stark contrast high or low?

Diniz Cabreira: Well, for instance the data I know because I am in it, from AGEA Editora, we typically publish the books in rounds of 100. Some of them have sold like three runs. That’s 300 books. In total, in aggregate, we have I believe, like something like 20 titles. I will have to check. So let's say…

Guy Windsor: 6,000 books.

Diniz Cabreira: Maybe, around that.

Guy Windsor: Yeah.

Diniz Cabreira: And we are a team of people not working professionally on that, so not working full time, of course. But we are a team, we have this way of cheating, which is that I own a print house.

Guy Windsor: Yeah.

Diniz Cabreira: That's great. And then we kind of have all the right ingredients to do this, maybe we can do it better or invest more time on that.

Guy Windsor: Okay. You're producing primarily reproductions of the treatises. Those sell like shit. They are the lowest sellers of everything, by a mile. My Fiore facsimile and my Vadi facsimile, they do okay. I mean, they sell more than you might expect. But the critical editions barely sell any numbers at all. Most people don't want to have to deal with that. They want the okay, here is the original, but this is how you actually do it. They want that level of intervention between themselves in the book. And I view my books, my training manual-type books as bridges to take people from where they are all the way back to the original book. And so hopefully, by the time they've read one or two of my training manual-type books, they will feel that they have the necessary tools to go and read the original book. You're not really comparing like with like if you are comparing critical editions of the originals with modern training manuals.

Diniz Cabreira: No, I know I’m not, but that goes along with what I’m saying. In the current scenario in HEMA the people like us who are putting out books, we are covering different areas. I mean in a year we are publishing mainly critical editions of Iberian Destreza manuals and then some ideas and stuff, but mainly that. Chidester is doing like these facsimile reproductions. Very nice and very precise. He's selling quite a lot of them, but he's not selling tens of thousands of them.

Guy Windsor: Because they are so expensive his Kickstarter campaigns or Indiegogo campaigns do make in the tens of thousands at least. I wish his profit margins were better. I had a conversation with him about how someone if is spending 300 dollars in a book, they could probably afford to spend $350. And that way you'd make $50 more that you can actually spend on things like food. So Michael up your prices, I said. And he was like, Yeah, but I want to make these accessible, no, I'm do the accessible shit, right. The cheapest possible, practical, so that people can get the information that they need. You're making a luxury product that is gorgeous and beautiful and done to the highest possible standards. You should charge the moon for it because people will buy it and you deserve to make an income.

Diniz Cabreira: The issue is, it would be nice to have Michael here so we could talk about it with him. I will probably talk with him at a later point. But I think the issue is compounded because first he comes from the Wiktenauer project from the idea of making all the sources very accessible to people, for free. It is in the motto of the Wiktenauer project and then he got into producing these facsimiles because he knew that good facsimiles are very expensive typically when produced by other publishers, by other sources. But I mean like very, very expensive.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. My 1.33, it cost me about $800.

Diniz Cabreira: Yeah. So when you compare it $800 with the kind of technical books that we may buy for $50 bucks, that’s a huge disparity. I think he's trying to bridge that the gap. But I agree with you that he could probably raise the price 50 or 100 bucks and he will still be in the midpoint between the two. That will be good for him, right? Let's hope he hears this.

Guy Windsor: Okay. I told him to his face like in person, the last time I saw him saw him, which last year.

Diniz Cabreira: We were talking about these things in Brescia and we will probably talk on that soon too. So. Okay. So back on track. So let's say about 30,000 books.

Guy Windsor: Something like that.

Diniz Cabreira: Are you comfortable with saying or estimating how much that has earned you?

Guy Windsor: It really varies year on year and it varies hugely from book type to book type and platform to platform. So if I sell a person direct through my Shopify store, if I sell them a hardback, I will make a lot of money on that transactions, whereas if I'm selling them an e-book on some discount e-book store somewhere, then I'm making almost nothing and it's the same book. So it's very hard to say. But my best estimate is the best year I've had so far, in terms of book sales, was the financial year 21, 22, and my book sales there were about $45,000. That's money to me.

Diniz Cabreira: That's money to you, the margin for you, discounting the costs of the printing, discounting layout.

Guy Windsor: Let me think. There was probably… I was running some ads then and there was some layout. The layout cost of the book as a proportion of the price, it goes the first book is very expensive, and every book after that is a lot cheaper. By the time you are 2000 books in, the proportion of layout costs is almost nothing. Depending on how old the book is, that has already been paid for usually. Should we say, I probably spent in that year about a total of maybe 10,000 on things like layout and advertising. And on other publishing costs, assistants and whatnot.

Diniz Cabreira: That's nice. Okay. That's an interesting thing, though, also that when you are running a publishing project, publishing house, call it whatever.

Guy Windsor: We call it Spada Press. So it is a publishing house.

Diniz Cabreira: Okay, That's nice. Okay then when you're running that the back catalogue that you have, that's your real asset. The next books that you produce, maybe an absolute best seller and end up selling millions of copies. But who knows?

Guy Windsor: Fingers crossed.

Diniz Cabreira: But in a more realistic manner foreseeably what we know is that the books we have, we can keep reprinting and selling them, and that's important capital.