Episode 188: Vadi and The Four Virtues of Sword Making, with Eleonora Rebecchi

Share

You can also support the show at Patreon.com/TheSwordGuy Patrons get access to the episode transcriptions as they are produced, the opportunity to suggest questions for upcoming guests, and even some outtakes from the interviews. Join us!

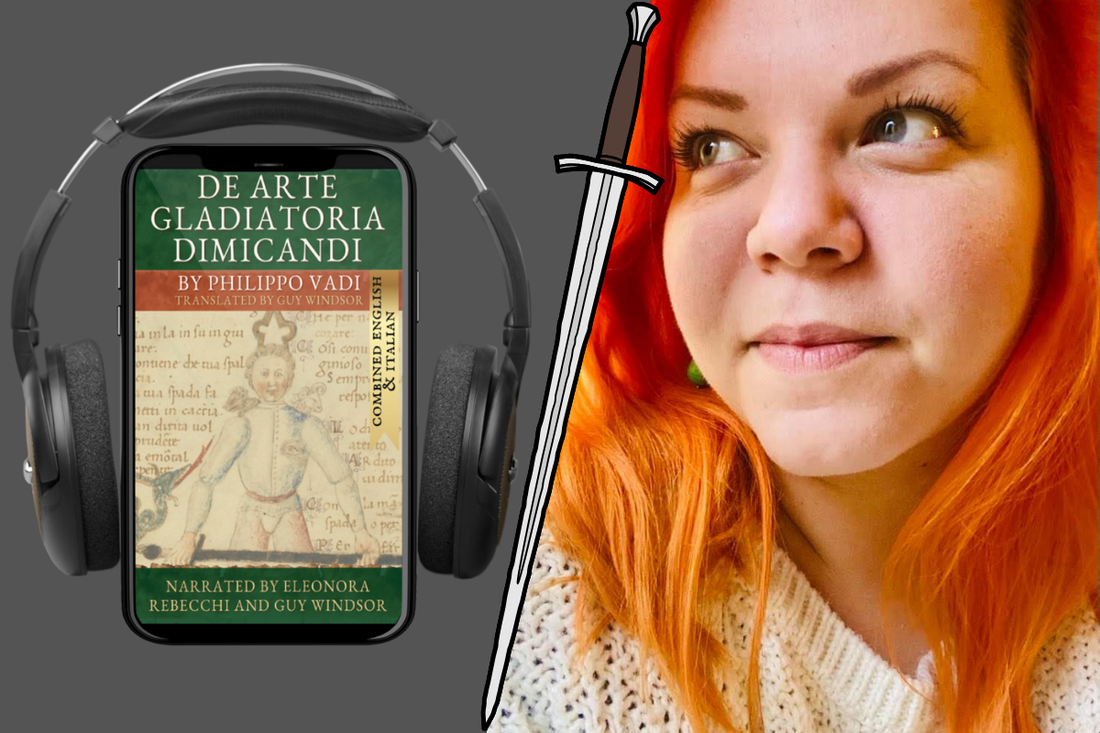

Today’s episode is a bit different to the usual format, as we have both a delightful sample from an audiobook and a related interview.

I have created an audiobook of Philippo Vadi’s De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi. It comes in three parts: 1. My friend, Eleonora Rebecchi (more on her later) has read Vadi’s words in mellifluous Italian. 2. I have read my translation in a rather more clunky English. 3. There’s a combined version, with the Italian chapter followed by its translation in English. Find the audiobook and more details here:

https://swordschool.shop/products/de-arte-gladiatoria-dimicandi-audiobook

This podcast episode contains a couple of sample chapters of the audiobook in both Italian and English, and it’s followed by a repeat of my interview with Eleanora Rebecchi (episode 129, October 2022). Here are the show notes for the interview:

Eleonora Rebecchi is the creative director at Malleus Martialis, producer of excellent training swords, as well as a practising historical fencer and a graphic artist who has done some lovely covers for Guy. She is also a classically trained singer, which you’ll get to hear in this episode.

We talk about how Eleanora and her partner Rodolfo got into designing swords for a living, what goes into the design process, and what qualities a business selling swords needs.

Eleonora explains how the aesthetics, ergonomics and dynamics of a sword fit together, which is demonstrated by Guy’s longsword.

Here is the unboxing video so you can see what he means: https://vimeo.com/722218823

Interview Transcript

Guy Windsor: I'm here today with Eleonora Rebecchi, who is the creative director at Malleus Martialis, producer of excellent training swords, as well as a practising historical fencer and a graphic artist who has done some lovely covers for me. So without further ado, Eleonora, welcome to the show.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Thank you. Thank you. It's such a pleasure to be here today. Hi Guy.

Guy Windsor: Hello. It's nice to see you again. Whereabouts are you?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, me too.

Guy Windsor: Whereabouts are you right now?

Eleonora Rebecchi: I'm in Italy, Florence. But I'm not Florentine, though. My home town is Mantua in Lombardy. I moved ten years ago in Florence, and that's the same year I joined Malleus Martialis. This is my story. The whole story.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, because I met you in Florence, oh, by the way, saying you just live in Florence has made probably 90% of the people listening want to kill you because they are so jealous. So, yeah, we met in Florence in, like, 2015. I don't think I've seen you in person since then. But just for people listening, what is it actually like living in Florence?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Well, it's kind of difficult if you live near the city centre. I lived there about 10 minutes from the centre when I moved. And I lived there for ten years, nine, more or less. Because then I moved to Impruneta. And there are, as you know, many tourists. And a lot of events. A lot of situations. For the movida, for the nightlife. So it's a city. And I really loved the fact that I was near those huge and wonderful works of art. Because living in Florence means you have many things to see every day. But if you're working hard, as I did in the last ten years, you have to organise well your time to enjoy the city properly.

Guy Windsor: So you're not living in the same place that you were when I met you in 2015. You’ve moved?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Exactly. Exactly.

Guy Windsor: So you moved out to Impruneta?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Absolutely.

Guy Windsor: I can see how that might help you get more work done, because Florence is a very distracting place.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But Impruneta is beautiful because you are on the hills. On the Chianti hills. So there are a lot of wineries. There are a lot of places to relax and take some time to also slow down. Because for me, work is a huge part of my life and I really, really need to slow down and chill and meditate.

Guy Windsor: Right.

Eleonora Rebecchi: I am a very calm person or I try to be a very calm person.

Guy Windsor: Okay. Is it true that you can actually sing?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes, it is. I devoted the most part of my previous life because it is exactly like this to study singing and classical singing. When I was a child, I was enchanted by Disney songs and I knew a lot of them by heart. So when I was ten, I went to my parents and said, when I'm a grown up, I will be a famous singer. Life brought me somewhere else. And even if it wasn't an easy decision, I know I did the right thing in the end.

Guy Windsor: So you actually trained professionally?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes.

Guy Windsor: Okay. Would you like to sing a little bit?

Eleonora Rebecchi: I knew that.

Guy Windsor: I'm here for the listeners, right? It's my job to give the listeners absolutely the best experience they can get. So would you sing a couple of notes if you like? Or we can cut this bit out if you say no.

Eleonora Rebecchi: That’s OK. Right now. There's a live action that's coming I really like and I am really fond of it. That's The Little Mermaid.

Guy Windsor: Okay. All right.

Eleonora Rebecchi: I know the Italian version. But I will try to. [Eleonora sings in Italian]

Guy Windsor: Bloody hell. You can actually sing.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But also we have Ursula. [Sings]

Guy Windsor: That was fantastic.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Thank you.

Guy Windsor: I just hope that my sound editing skills are up to the task of making that sound as good on the recording as it should do. So you were heading towards being a professional singer. So what stopped you? What made you change your mind?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, I think that mostly money and wrong decisions during the path led me to stop with it. I really wanted to make a classical singing career. I wanted to sing in the theatres and making auditions and so on. But these took a lot of resources from a money point of view and from financial point of view. And I wasn't that wealthy for the process and also I really liked to teach and to share my knowledge about classical singing. And that was another thing that I could have developed through the years. But in the end, I said to myself, if I can't do this properly, and as it was meant to be, I won’t make it. That's the deal. You know, it was so precious and so important to me that I wouldn't want to make it not properly as I wished.

Guy Windsor: Right. Yeah. I think if I couldn't do swords for a living, I'd probably stop them altogether, for the same reason. I’m 100% or nothing.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, exactly. And there were many tears at the time.

Guy Windsor: So there's like one particular day when you said, right, no, I quit?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes. And I never sang again. From that moment on.

Guy Windsor: Well, you just did.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes. With friends. Or when I shower.

Guy Windsor: But not on stage.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

Guy Windsor: Okay. That must be pretty hard.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But historical martial arts came in that period of my life.

Guy Windsor: Okay, so you traded singing for the sword?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, exactly.

Guy Windsor: Well, if you had ever heard me sing, you would beg me to try singing for swords.

Eleonora Rebecchi: I don’t think so. Everyone can sing. You only need some practise.

Guy Windsor: In theory, I believe that every skill can be learned. Absolutely. But I don't think the world would be better off with me singing in it, to be honest.

Eleonora Rebecchi: We can sing together one day.

Guy Windsor: OK. In Italy with enough wine. Let's do it. Absolutely.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Great. Deal.

Guy Windsor: But no recordings. No, no.

Eleonora Rebecchi: No, no, no. I promise.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So how did you get into historical martial arts?

Eleonora Rebecchi: It was the dark period when I was deciding what to do. And I graduated in 2011 in the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. And after that, I was forced to come home again to Mantua. And that wasn't positive for me. I wasn't happy, but I needed to build a new life in my hometown. So I joined the re-enactment group to practise historical fencing because I was fascinated by the history behind the sport and the harmony of this discipline. That's why.

Guy Windsor: But it's a long way from doing historical martial arts with the re-enactment group in Mantua to running a sword making business in Florence. So what were the gaps?

Eleonora Rebecchi: The gaps are that I met Rodolfo. One year later, I joined this re-enactment group and started to practise fencing at an event. At the re-enactment event in Italy.

Guy Windsor: Just the listeners, this is Rodolfo Tanara, who makes most of the swords at Malleus Martialis.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Exactly, the sword maker. Right. And we met at this event, and we decided to, I don't know. We didn't get engaged in the first place, but now we are engaged.

Guy Windsor: Congratulations.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Now, after ten years we can say so. And that was his dream because he always wanted to make swords for a living. He started to be a doctor before. And when I saw the project, I knew he needed a sidekick to help him in the everyday papers, design, the promotion of the products and so on. And in a way, I was the right person at the right time. And so this is the situation. We liked each other almost immediately. And after some years, I said to him, you need me, take me.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So. So that's how Malleus Martialis started as a business. But Rodolfo had been making swords before that.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah. He was making swords in his free time and they were starting to make them also by learning from blacksmiths and so on and from books, of course. But in the end, he decided to open the company and it was quite challenging.

Guy Windsor: Was that 2015? 2014? I think you had just started when you had just started as a company when I met you in February 2015. And we went and visited the workshop where stuff was being made. And let me be frank. At the time I thought, well, yeah, this is okay. I had no idea that you would start producing such gorgeous swords. I mean, it wasn't it wasn't obvious from where things were at the beginning of 2015 that you would ever be producing swords the way they look now. So I don't know what happened. Obviously Rodolfo learnt his craft, but I think probably the sword design is part of what changed also. Is that fair?

Eleonora Rebecchi: And I think that the real reason why we improved through the years is surely that we joined our forces and our skills, but that we were able to learn from our errors because we did a lot of errors.

Guy Windsor: Of course.

Eleonora Rebecchi: And it was like opening a company without any idea about what a business is.

Guy Windsor: I was the same. Yes.

Eleanora Rebecchi: Yeah, let's do it!

Guy Windsor: Let's just do it. Just do it. And you'll learn how to do it as it goes. That was my approach. And it worked for me, it worked for you.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But yes, surely the communication between us and the joining of design and craftsmanship were developing together and improving together. It was something really important to make the swords we are making now.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So what do you think makes a good sword?

Eleonora Rebecchi: I think that when aesthetics meets proper dynamics and ergonomics, you have a good sword.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So aesthetics, dynamics, ergonomics. All right. So those are three kind of technical terms, and I think I understand what you mean. But I'm guessing that some of the listeners might not, and I may be completely wrong too. So aesthetics: what the sword looks like. Ergonomics is how it handles. So what is dynamics?

Eleonora Rebecchi: The ergonomics is also how it is in your hand because many times the grips and the parts you actually handle, is not taken seriously.

Guy Windsor: I know! Okay. I literally just posted a video where I took this this cheap training rapier. And the one thing I had to do to make it work well as a sword was fix the handle. That's all it needed. But the handles that generally come on swords are, for want of a better word, shit. They're not designed as an interface between the blade and the body. They're designed as a piece of wood that you can wrap your fingers round so you don't drop the sword. That's not what the handle is for.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah. Also because, for example, depending on the main characteristic of the sword, like for example, you have a sword that mainly thrusts or you have sword that mainly cuts, then the grips are different and the shape of them are different.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, but okay. But they're different in a way that you can see and I can see and I can certainly feel. But I don't think most people who aren’t sword people, I mean, anyone can tell the difference between the longsword and the rapier, just by looking at it and go, oh yeah, the one with the fancy bits around the handle, that's the rapier. But these sorts of differences we're talking about are matters of nuance and degree, I would say. So how would you describe the difference then between a primarily cutting handle and a primarily thrusting handle?

Eleonora Rebecchi: In my experience, it's about the position of the hand on the grip and the shape that derives from it. If you have to cut, you will have a very precise alignment of the arm and the sword will have a more flat hand grip.

Guy Windsor: Okay.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Whereas if you have to thrust and if you have to go in circles with your hand and with your sword, a more rounded shape of grip is recommended. Of course, every sword has a different kind of grip. And I'm really, really trying to make a summary of these concepts, you know?

Guy Windsor: Yeah. Well, my rapiers, they tend to have like a flattened octagonal section. Whereas my longswords tends to have a kind of slim oval cross-section.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But it's also about the thickness of the grip. And of course, it also depends on the length and on the weight and on the techniques you have to apply. For example, a smallsword we go to two very different swords and the smallswords will have a very oval and rounded and grip in the front profile of the of the grip.

Guy Windsor: But it's very slim and very short.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, exactly. While a longsword will be, if you have to cut and thrust because longsword does everything.

Guy Windsor: It’s a Swiss Army knife, really.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes. It will be something in the middle. That's why I said that I was trying to give a very short summary of the concept because it's very huge.

Guy Windsor: Well, here's a thought for you. An axe handle. Pretty much everyone knows what that looks like. It's sort of very flat and quite wide, but slim. So if the axe is in your hand it is quite wide from wrist to finger, but it's quite slim from palm up. Which gives you perfect alignment when you're chopping that tree. Whereas a spear tends to have a round section.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Exactly.

Guy Windsor: Although spear handles that are made in the traditional way with coppiced poles are slightly oval.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: And octagonal. So you can kind of feel your edge alignment. So you do get your edge alignment. These modern machine-produced spear poles, they don't give you that edge alignment, which is a little bit annoying to me because I'm a bit of a purist.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Exactly.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So that's ergonomics. What about dynamics?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Dynamics is how the sword moves.

Guy Windsor: Sorry to interrupt you, but my new longsword. The thing I don't understand about it is it's light and it has that kind of light, accurate, precise feel to it, but it still hits like a motherfucker, right? It's like it should be if it can hit like that, it shouldn't quite handle like that. It's a little bit like having kind of Ferrari agility, but tractor-like torque.

Eleonora Rebecchi: There's a reason why.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, tell me. Because I don’t get it.

Eleonora Rebecchi: The reason is about the dynamic properties related to the shape of the sword. That particular sword is a longsword based on German findings.

Guy Windsor: I'll put a picture in the show notes so people can see it. I'll also put the unboxing video so people can see me handling it. And then maybe people will understand because when I was handling it, I had that, “Huh? How the fuck can it do that?” moment. I will put that in the show notes as well. Sorry, carry on.

Eleonora Rebecchi: The shape of the of the blade is really the change maker. Because it is narrow, but at the same time, it has parallel edges. This gives you a presence in the bind more than...

Guy Windsor: So I just went to get it off the rack. So it's got from the handle to about two thirds, three quarters of the way down the blade, the edges are almost parallel.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Exactly.

Guy Windsor: Okay. They are not strictly parallel. But they're only tapering very slightly.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Exactly. If you compare it to an estoc with the triangular shape of blade and then you will have a lot of presence in the last third and less presence from the middle two to the end. And that's because of the shape and the anatomy of the blade. So the miracle is made by, of course, the tapering, of course, the various parts, but in this case, from the shape of the blade.

Guy Windsor: Okay. And I imagine there are some sort of trade secrets in exactly how that's accomplished. But anyone who comes to my house is welcome to have a look at my sword so they can maybe figure it out from that. Okay. So do you actually design all of that yourself? Okay. I make stuff. And when I'm making, for example, a chest of drawers or something, I'll have the external measurements where it needs to fit. And so maybe it's this wide, this deep, this high, and maybe I know I want this many drawers and then I just go into my workshop and just make it. I don't measure anything other than the external measurements. Everything else is taken sort of from itself. So like the thickness of the wood, it may turn out a bit thick or a bit thin and it doesn't matter. I don't get it to a particular thickness. I make it look right, feel right, and just sort of do it all in the process. Okay. Whereas I think you're actually designing things. You're thinking it out clearly in your head first and then giving Rodolfo pretty specific dimension things. So here, go make this precisely.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, exactly.

Guy Windsor: Okay. Right.

Eleonora Rebecchi: The real value that Rodolfo brings after the design is that I always give him approximate information about the blade because yes, he has the design, he has the shape. He knows that the blade has to behave in a way that I figured out in the beginning when I started to design it and accomplished it. But he knows how to make it work, you know.

Guy Windsor: Yeah.

Eleonora Rebecchi: When we join, this is our great strength and it's about the fact that we are able, we learnt and now we are able to communicate and that is something that I want to highlight because now I already tell about this some minutes ago, but this is the secret. The secret of the trade is communication.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, that makes sense. And I have friends who are swordsmiths and there's absolutely nothing worse than a customer sending a design to a smith who actually hits things with hammers and the design is like to a tenth of a millimetre in every dimension, because there's just no scope there for the smiths to actually apply their art, right? It's like treating the smith like a CNC machine. But on the other hand, you have to give just enough information that the smith knows what you want and then they can apply their skill and experience to actually producing it.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Mm hmm. Luckily, I don't think I have ever accepted a work in this way. I never had a customer or if there was someone, I said no.

Guy Windsor: Right. Exactly.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Because luckily, I can choose to enjoy my work. And this is something that I always like sharing experiences and sharing impressions with the customers. And also if they send me a sketch, if they send some preferences, it's something that I really love because we communicate again.

Guy Windsor: Right. Yeah. Although I think when I order custom stuff, like the last time I ordered a custom bullwhip, for example, I said, I need it so that the lash is eight foot and then you've got the fall and the cracker, which adds to that, so total reach is maybe 12, 13 feet. And I said, okay, so I need an eight foot bullwhip. Make me the eight foot bullwhip that you don't want to let out of your shop because you want to keep it for yourself. Because the guy I was ordering it from, a guy called Alex Jacob, he knows vastly more about bullwhips than I will ever know. And he is an amazing sort of whip cracker and expert in that area. And there's just no way I'm going to know more about, you know, what will make a good whip than he does. So I needed an eight footer. I said, Alex, make me an eight footer, make me the one that you don't want to let out of your shop because you want to keep it. And sometime later, I got this absolutely glorious thing. It is just so precise. It is as loud as a 44 magnum going off. And it is just a brilliant thing. I wouldn't have known exactly what to ask for. I think it's a good approach to getting your makers to make stuff. But if you are a designer, you need to be a bit more precise than that.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah. And that's why the work behind is really detailed. And even if I have to choose hour long the grip has to be, how long the cross guard, or, for example, even how wide the blade has to be. All these little tiny aspects that maybe someone can simply take an original and say, okay, I have the original. I will do it exactly the same, or more or less exactly the same. I will think about it also because, first, it's very difficult for us to approach museums, still. We have some very good relationships with some museums in Europe, but they are few and they don't have so many available data. So every time I need it, I collect as much as I can, as much data as I can. But when I have to design, for example, a sport piece or a collectable piece, the processes are completely different and the thinking behind is completely different. And even when I have to deal with an original reproduction, a reproduction of an original, the deal for me is that I can’t make sharp swords, Malleus Martialis can't make sharp swords.

Guy Windsor: Right. Because the law in Italy is really fucked up about that sort of thing. It’s weird.

Eleonora Rebecchi: We don't produce time because we don't have the authorisations required to do that. And it would be a great investment for also the company in general because we should have those security systems and the serial numbers. And we would have to take an exam and maybe one day we will do it.

Guy Windsor: I've got a better idea. Just move to France or Germany or Britain or Finland and Sweden or any other country except Italy, and the you can make whatever the hell you like without any restrictions at all. So as long as it doesn't actually explode, nobody cares. Itis just Italy that has these really screwed up sword laws. I've just had an idea. You design these amazing swords, right? And Rodolfo makes these amazing swords in Italy. I don't think you actually want to move to France. All right. But have you thought about getting your swords made. Getting sharp swords made outside of Italy. So long as they are not being brought into Italy. So you're selling it to your customers, like your customers in England, for example. You could get swords made to your specifications outside. Is that possible?

Eleonora Rebecchi: This is something that I thought. But it's difficult because sharpening a sword requires knowledge, you know? So, for example, if a customer says to me, oh, listen, I would like to have that sword, and then I will sharpen it, and I say, yes, absolutely. If I have to give this work to another smith, for example, outside Italy, the smith has to be available to do business with me.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. So it's complicated.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, there are some issues.

Guy Windsor: But the reason I thought of it is that a friend of mine who does custom work, knives and swords, unbelievably beautiful knives and swords. He also designs knives for his cousin who runs a weapons shop. And they get those knives made in Pakistan. And actually, they're really good. They're really good. And they make loads of money.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: So it's just a thought.

Eleonora Rebecchi: I will think about it.

Guy Windsor: Because you have all this fantastic intellectual property, right? These designs that you've made. Which is your intellectual property. That should be ways of making it.

Eleonora Rebecchi: About that. I had some issues about intellectual property recently. I can't explain it in detail because it involves another producer.

Guy Windsor: Let me guess. Did somebody ‘borrow’ one of your designs?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes.

Guy Windsor: Motherfucker. You can name them and shame them here if you like.

Eleonora Rebecchi: No, no, no. Even if we cut, I won’t do it.

Guy Windsor: No, fair enough.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Also because they were available to understand that there was an error and to put down the material from their channels.

Guy Windsor: Okay, so they behaved reasonably.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, absolutely. Very kind and reasonable.

Guy Windsor: Then perhaps maybe they should just licence some designs from you.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes. Why not?

Guy Windsor: Because if sword makers are looking for designs. Licencing a design from you saves in a ton of time. And then also it provides a small income stream into the company that doesn't involve you actually having to get out of bed in the morning. And Rodolfo can, you know, have a day off. And the company still makes a bit of money.

Eleonora Rebecchi: It could be. It could be. It's a nice idea. And about the intellectual property there's an issue that the intellectual property can be registered if the property is innovative and it is new and something that has never been seen before, you know, because it is industrial property, it's not like an artistic property.

Guy Windsor: Ah. Soy you can't licence it as an artistic copyright. You have to licence it under like a trademark or a patent. Well, hang on, though. Companies that produce art professionally and books, for example, they get artistic copyright on their stuff. So just the fact that you’re a company shouldn't make any difference. So you could certainly get, I mean, your designs are, if I understand international copyright law even a little bit, your designs are copyrighted to you pretty much automatically. It's just it can be difficult to prove that this sword that you designed has now then be copied by somebody else. Because swords basically look the same to a non-specialist.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah. And also they are based on original or already invented artefacts.

Guy Windsor: True. Yeah, well, we sort of stumbled into the whole business side of things. So what is actually like running a sword business?

Eleonora Rebecchi: It's kind of tough. Yes, because as I said before, when we started, we really didn't know anything about business and instruments and tools and so on. And why open a company if you don't know how to do business? Well, when you're young and enthusiastic, you take foolish choices.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. Like moving to Helsinki and opening a sword fighting school when you have no qualifications, for instance. And that seemed to work out alright.

Eleonora Rebecchi: In fact there's a famous aphorism amongst the Start-Uppers and that's fake it until you make it.

Guy Windsor: That's right.

Eleonora Rebecchi: So it works. Well, we survived the first years learning and learning and learning four important things, to be cautious, to be bold, to be quick and to be strong. Following the Fiore.

Guy Windsor: For non-Fiore listeners, those are Fiore’s four virtues that a swordsman should have. Okay. Be cautious and bold and swift and strong. That is fascinating. I have actually written a piece on how Fiore’s four virtues applied to business. I've never published it, but it's there on my hard drive. I haven't quite figured out why I would publish it. So tell me when you say what do you say ‘strong’, what do you mean?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Stable. Stable and extremely tough against issues and everyday difficulties.

Guy Windsor: It's like determination, then.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, absolutely. Constance and determination always.

Guy Windsor: Caution?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Caution. It requires discipline and also wisdom. Because when you approach business, you have to understand which is the right direction, where to invest your money. Where people have to improve their skills and, you know, time is money. So when you improve something and you invest your time, you are also spending your money. And then also choosing the right materials, the right machines. For example, some years ago, we, I decided that I wanted a little CNC machine to practise. To practise and to learn and also to make little things. And it was a very silly expense and I realised it only after a couple of months that the CNC machine was already purchased for example. This is an example of course, but it is really important to understand that when you deal with money and you don't know how to use your money right, maybe you make a lot of products, maybe you make a lot of expenses, you buy a lot of machines, and in the end you really need less.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. Okay. So what about speed?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Speed. Speed is about understanding the right timing and understanding when you have to make the next step. It's exactly like in fencing.

Guy Windsor: Because, I mean, I assume it would also include things like making swords faster so that you can make more of them. But that's the kind of obvious application of the idea.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But of course being quick in your job comes with time because you practise, practise and practise. And then right now, for example, being a very small business as we are, we are able to make around 70 swords, 60-70 swords every one month and a half.

Guy Windsor: Wow, that's pretty quick.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: That's a lot more than I expected.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: Good. That's excellent.

Eleonora Rebecchi: And it's really, really difficult to always keep the rhythm in the right way, because sometimes there are issues. Sometimes some partners and suppliers don't act as they should or they are late. So the managing plus being able to stay on time, it is something really important and of course organisation is about also being quick.

Guy Windsor: Right. I didn't realise that you are that productive. That you are able to produce effectively a sword in a half a day.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: That's a lot. By hand. For a small business making swords, that is a lot. Wow. I am very impressed. Excellent. Okay, so that's speed. What about boldness? Buy the CNC machine, god dammit! Buy a bigger one!

Eleonora Rebecchi: Exactly. Boldness is about a lot of aspects in the business. I was always and Rodolfo too, we were always not bold enough in presenting our product, in presenting our, our skills because we always feel in depth and we always feel we are not enough. And we know that we don't have to. We absolutely know that.

Guy Windsor: But imposter syndrome is real.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, it is. But if we learn to be a little more bold through time and also to make sometimes bold and difficult choices, also dealing with the employees, dealing with customers and partners. I think that boldness is a virtue that really helps.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. And in my experience, where it counts the most is firing bad customers. Like when somebody is just annoying, then refund them all their money and tell them to go away.

Eleonora Rebecchi: I get it.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, I bet you have. And it is so difficult to deal with. It's like you need customers. Otherwise, your business is going to fail. But if you're spending all of your time with customers who are just, you know. And it's been my experience, particularly on crowdfunding campaigns, that people who put in a big chunk of money are always absolute lambs to deal with. No problem. Things are a bit late, their fine. You know, you have trouble. You send out an email saying, sorry about this, something or other, I’m working on this and that. They're fine with it. Someone who's put in like €5 or €10 or something. They're the ones who are going to email you saying poke, poke and could we do this? You could do that and do that. So that's why the last time I ran a crowdfunding campaign, I didn't have any of the tiers below about €20 because in my experience, while, yes, it's nice for people who want to support the project to be able to check in a few euros. That's a nice thing in both directions. It opens the door to the people who are just going to be a giant pain, so it’s better just to keep that door shut.

Eleonora Rebecchi: I understand that. And I also think that maybe yes, sometimes people are really interested in our projects and want to participate in a very long conversation. But also sometimes maybe I am not able to make them happy, maybe I am not understanding properly what they are saying or what they are asking. And that's why, for example, from last year I started to ask for a deposit for the design. Because in the beginning it was, yes, I would like this, this, this, and I sketched that. So even 15 minutes of my life to sketch it that were lost, if the customer in the end didn't decide to go on, you know. So it's also about I think it's about rules and I don't know, a code between the customer and the producer.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. I just had another idea. Right. Okay. Because I've organised my business side of things to emphasise scalable products that can be sold automatically, online courses, books, that kind of thing. All right, but, I just had an idea. Your designs. See, I've not actually seen what the design looks like when you draw it out and stuff. Okay, but how hard would it be to make a poster with a photograph of the finished sword and the designs and sketches next to it as a kind of this is like the architecture of your sword. Which could it be like an add on, like, I buy a sword for 500 euros or 600 euros or whatever. And for another like 20 euros you can get a poster of your sword with like the actual dimensions of stuff and you can stick it on your wall. Wouldn’t it be cool. And then people could just buy the poster and these things can be printed on demand. And that way if they put it up on their wall, they're literally paying you to hang an advert for your company on their wall in their salle.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Absolutely. Absolutely. It is a very good idea.

Guy Windsor: Yeah.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Okay. Recently, several people asked me to make some merchandising. So posters or even shirts, or mugs. I love mugs. I have a collection of mugs. It would be really, really nice with the designs and of course logo or art stuff on it.

Guy Windsor: Have a merch shop. But I'm thinking, because your graphic design work is gorgeous. I saw that poster you did for my friend Chris VanSlambrouck’s seminar when he came to Italy in 2015. And it was just like, fuck, that's just a work. It's the only seminar poster I've ever seen that is just a work of art in its own right that you just hang on the wall. It’s amazing. That's why I got you to do those covers for me. So you have that skill. And you're putting so much work into the designs themselves that, you know, I'm sure you could create something that is just gorgeous, that has the design stuff, the sketches and measurements and things and the drawing, maybe the saw and maybe a photo of the finished sword or something like that. And then the Malleus Martialis and maybe some other things, whatever. But I'm not a graphic designer, I don’t know shit about such things. I hire people like you to do that for me. But I mean, it would be beautiful sword art that people can buy while you asleep. And somebody else prints it, posts it, and then sends you the money.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah. I really understand what you're saying. And in this regard, beyond working on the merchandising as soon as I can, we are still designing our way to scale the business in the future, because right now we are at our maximum capacity of production.

Guy Windsor: Right. That is a lot of swords. So how many how many staff do you have?

Eleonora Rebecchi: We are Rodolfo, Fabio and Simone in the smithy.

Guy Windsor: That’s three guys. Okay.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But Simone is hybrid because he stays between the smithy and the office.

Guy Windsor: Okay.

Eleonora Rebecchi: And in the office, there is Sergio and in a part time that helps me in managing customers from this January.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. I've had emails from Sergio telling me my sword is going to be ready or whatever.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Exactly. So we are five.

Guy Windsor: Okay. Yeah, that's not a lot of people to produce that many swords. Particularly when two of them aren't smiths.

Eleonora Rebecchi: And so I am studying a way to grow and I really look forward to this Malleus 2.0 in the future.

Guy Windsor: I have another product idea. Something that would be kind of cool. This might be video or it might be a series of images. It might even be a book of how a sword goes from an idea in your head to a sword in somebody's hand. That's a process involving research and design and experimentation and sketches and all that sort of stuff. Then selecting the steel and making it and making the handle and stitching the leather and all that sort of stuff. Yeah, that by itself, there's lots of ways to make that process into a product that can scale. Like of this being books, video, posters, even a video course. If someone is interested, maybe an online course on how to design a sword. That can scale.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes, absolutely. We will have to find the best way to scale. We are still working on it. And these ideas are all really, really good.

Guy Windsor: You know, I've been trying to make a living doing this for a long time, so. If you use any of my ideas and make a metric fuck ton of money I will happily accept a free sword as a little thank you. That would be fine.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Be able to, for example, organise giveaways or auctions. But in a very free way, I will always remember you. And I will give you a sword.

Guy Windsor: Excellent. We talked a lot about sword design. So what do you think of Peter Johnston's theory about geometric sword design? Which if I just summarise it briefly for listeners who may not have heard of it. Peter had this idea that, which I think is probably right, that the way swords were designed were entirely proportional, rather being strict measurements. They were like, you have a straight line and you have a series of circles on those lines, on that line which intersects, and there are all sorts of ways of creating reproducible, scalable designs that way that are based on something intrinsic to the future owner. I met him at Helsinki Knife Fair years and years ago. It must be like 2011 or something. And he told me this theory and that made me think about Vadi and that's what triggered me actually translating Vadi because Vaid mentions geometry in his thing. So that's how I ended up doing a translation of Vaid because of that conversation about that design idea. It also got me into geometry, so like sketching stuff with just a ruler and a pair of compasses or dividers and you can make all sorts of patterns that way, which is just to super fun. I don't have an opinion about how historically accurate his theories are, but what do you think?

Eleonora Rebecchi: First, I think that the theory is amazing and that it's a very fine method for the reconstruction of ancient swords and related reproductions. Though I don't use it for every sword I design. Even our ancestors didn't use it for every sword. Of course it's a theory, so we really don't know if they used something like that. But we can approximately tell that if architecture was designed after some rules and art followed those rules even sword design could follow proportions and golden ratio rules and so on. And some swords, some original swords after. Also, Peter Johnson's studies don't follow necessarily the same rules every time. For me, it's the same. If I have to make a design for a high hand and specific commission, I can use it. Otherwise, I will take several examples of the original swords and the average stats to design the models. I won't go every time with the golden ratio design.

Guy Windsor: Okay. That makes sense. And I think is almost certain, or as certain as we can reasonably be, that some smiths or sword designers at some point in medieval Europe will have used these sorts of methods because that's how people drew stuff. It certainly wouldn't be every smith every time. And I think sometimes it wouldn't be nearly so complicated because once you're making things with your hands, after a while, once you've got the gross dimensions, you won't carefully trace out this curve on the pommel so that it matches this curve on the cross guard, according to this particular geometrical regime, you just do it by eye. And it will look perfect if you're a really experienced maker.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But for example, even the blacksmith who has to make a gate for a house uses patterns, he uses also repeated measures to create the whole design and to fit the gate into the house. So I think it's the same process for the sword maker and especially maybe not for steel production. So I don't think I use a very different process in comparison with our ancestors because the production doesn't follow every time a redesign and the design is made one time. It works, the proportions work. And so every everything can be produced. And if on the other hand, if you have to deal with that sword for that nobleman or that guy who wants something very special for him, then you go with something more special as well.

Guy Windsor: So do you design on paper or do you do it on a computer?

Eleonora Rebecchi: I do it on a computer.

Guy Windsor: Okay. That's definitely not medieval.

Eleonora Rebecchi: No, absolutely not.

Guy Windsor: It’s funny because I've tried for woodwork. There's CAD software called Sketch Up which is cheap and it's very good and whatever and I just can't get on with it. When I'm designing something that I'm going to make I use a pencil and a piece of paper and sometimes a ruler and occasionally a compass. But that's it. I can't do it on the computer.

Eleonora Rebecchi: When I have to understand what pommel, what guard, what blade, the first sketches I made on paper because I need paper to think. But when I have to develop the entire design, I go on the CAD software. Absolutely.

Guy Windsor: That makes sense. Yeah, it's like I'll often plan a book with a pen and notebook, but actually write it out into the computer because I'm too lazy to write it out by hand and then type it up. Okay. So what is what is your favourite thing about the job?

Eleonora Rebecchi: My favourite thing, I think that it’s people, both my mates, my colleagues and customer. The relationship I am able to create. Because yes, sometimes they both make me nervous because I'm not Gandhi. But I truly love to serve them and to share laughs, memories and the path with them. That the best part of my job.

Guy Windsor: Okay. That's not what I expected. I expected it would be the design. I thought that sketching out swords would be the best bit, but no, okay. Yeah, I guess like with swords, teaching swordsmanship, the showing up in person and teaching in person so everyone is in the room holding a sword and we're all in the room together. That is the best bit for me.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Because we are givers.

Guy Windsor: Well, it's a fundamental social thing. And, you know, when somebody comes to you because they want the sword and you make the sword and they get super happy about it, it's just a positive cycle.

Guy Windsor: So what is the best idea you haven't acted on yet. Apart from of my brilliant product design ideas.

Eleonora Rebecchi: And this is the most difficult question of all. And even if I had a best idea, I couldn't tell because I am very jealous of my ideas.

Guy Windsor: Interesting. I give all mine away. The hard part isn't having the idea. The hard part is the execution. Because most people can produce ideas left, right and centre, but it is difficult to act on some ideas. It's difficult to take something from an idea in your head, to actually make it a physical reality in the world. That’s hard.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah.

Guy Windsor: So I don’t have to worry about people stealing my ideas.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Mostly because when I have an idea, I tend to work towards it. My ideas are not fantasies. My ideas are willings, you know.

Guy Windsor: Right. Okay, I understand that difference. So your ideas are not just fantasies in your head. They are things you are likely to act on. So in which case, let me let me rephrase the question. What idea is next to be acted on?

Eleonora Rebecchi: I think that I am developing the business by also working on its processes is the next thing in line. Because my dream, our dream is to bring Malleus to another level. We don't want to stay as a small craft business for all our lives.

Guy Windsor: Oh, okay.

Eleonora Rebecchi: We want to bring our craftsmanship and our love for swords and our skills to serve the community in a wider way. So I have lots of ideas about that. And right now I am working on new designs to be able to scale a little bit more the production in the future.

Guy Windsor: Wow. So it's going to be I can go into my supermarket and buy a Malleus Martialis sword next year. I’ll have a bunch of bananas, I'll have a packet of coffee and I'll have a longsword. Thank you very much, brilliant.

Eleonora Rebecchi: No, no, no, no. You will go in a wonderful palace full of diamonds and golden stairs. And there will be a man who will come to you and say take a look to the wonderful Malleus swords.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. Okay. More Louis Vuitton than Aldi.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, exactly. Excellent. You perfectly understand.

Guy Windsor: Well, good. I'm glad that you're aiming high.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, absolutely.

Guy Windsor: I guess one of the issues at the moment is you have quite a long lead time. It's like four or five months usually.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah. Around six.

Guy Windsor: Six months. I guess if your production was wrapped up to the point where you could clear the backlog and actually get a stock in so people could buy it and have it next week.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But we already have something like that because our production is always divided into categories. The commissions for the customers and the in-stock products.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So I am going on to your on your website right now. I’ll have a look at what you've got in stock. While I am indulging myself like this, what made you call it Malleus Martialis in the first place? What does it mean?

Eleonora Rebecchi: It means the hammer of Ares, of Marte. The God of war. I really don't know where it comes from because I really didn't ask Rodolfo where the first idea came. I don't know why, but I never did it. Because it sounded cool and yeah, okay, that's cool. But I think that it was because in the beginning he really wanted to learn how to hammer the metal. And he was really interested. And he was an historical fencer himself. So the two souls, the forge and the fencing together.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So it's the Hammer of Mars. And while you said that I was fooling around on your in-stock thing. You actually have an Einhorn Messer in stock that you have subtitled Mr. Bad Guy. It's like you're trying to tell me something.

Eleonora Rebecchi: It’s light but aggressive. So it's like Freddie Mercury in his golden years.

Guy Windsor: Fantastic. Oh, it’s a beast. Oh, yes. Okay. Right. Put your credit card down, Windsor.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But by the way, we always keep some stock available, until it is finished, of course, because it's really important to us always to offer a ready made or ready to buy swords. Of course, we have to make the commissions, so for custom orders we take some more time. For the usual swords, for example side swords, maybe you can have it in one month and a half because in stock we always have, for example, something that we give to the customers when they contact us and they reserved it, you know. So it's something that is working. But to be really, really quick and to go and cut the six months when we don't make a particular product frequently, then we need other methods, other processes for the future.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, tricky. Okay. So you're going to have to come back on the show in a year or so and tell us that you have cracked the problem and now anyone can just go in and get whatever longsword they want, or sidesword or whatever else. So, my last question is someone gives you €1,000,000 or similar sum of imaginary money to spend improving historical martial arts worldwide. How would you spend it?

Eleonora Rebecchi: I think that $1,000,000 is maybe more than I need.

Guy Windsor: Really? Most people say it's not enough. Okay. So what would you do with it?

Eleonora Rebecchi: I will try to answer. I would heavily develop the firm and its processes quicker.

Guy Windsor: No, no, no. You can't spend it on you or your company. Like, if I had the money, I'm not allowed to spend it on copies of Capoferro from 1610, or Malleus Martialis, or whatever else.

Eleonora Rebecchi: But I serve the community. And so do you with your Capoferro.

Guy Windsor: Honestly, I think the community can maybe. I could take that money and use it to do what I already do a bit better. But it's not going to make a gigantic difference in the same way that, for example, I mean, one suggestion has been a sort of a fund so that groups that are starting up can afford a set of equipment, swords and masks and whatnot to help them get started. That would make a bigger difference.

Eleonora Rebecchi: I think that I would organise and fund the more events and exhibitions about swords and historical fencing, where we can meet, promote, learn, design, and also training children to this art. So surely. I would invest avidly in events and exhibitions. This would be my target goal.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So maybe funding some events that will get people started or for people who are already practising and as if the event is funded, then maybe there'll be some free places open, and possibly even some travel grants to get people coming.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, why not?

Guy Windsor: And of course, you know, all of these events would be sponsored by Malleus Martialis, and here is an enormous table of swords that you can buy while you are here.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Of course.

Guy Windsor: Of course. Naturally.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Anyway there's something more that I would do. It's not about the whole community, but it's about the ones who would be willing to do it. I really would like to invest a great part of this money in education. And education has always been a big part of my life. Even when I sang, I wanted to teach singing. And when I started to make reenactments, in the end, I ended up making my own association and teaching.

Guy Windsor: We didn't talk about that at all. Okay, so you started your own historical fencing club?

Eleonora Rebecchi: No, it's not about historical fencing club. It's re-enactment. I really separate the two completely. For example, I led this association until last year when I said, this is the time I leave.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. So what was the association?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Its name is Gonfalone Del Drago and the association in Florence who re-enacts at the end of the 14th century. When we started, we really wanted to make things right with the research, with the proper reconstruction of tools and clothes and so on and living history.

Guy Windsor: Okay. So it's a full on living history, physical culture, material culture, re-enactment group. Gonfalone Del Drago. The Banner of the Dragon.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah, exactly. Because there's a quarter in Florence which is divided in four parts. Every quarter in Florence is divided into four parts. And one of the quarters of Santo Spirito quarter is Gonfalone Del Drago.

Guy Windsor: Oh right. So you named it after that. Fair enough. Okay. And I assume that most of these people are re-enacting using Malleus swords, right?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes. But not only. Also for example, Tod.

Guy Windsor: No? OK. Tod Cutler. He makes some very nice stuff.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yeah. I really admire him.

Guy Windsor: Yeah, he's very good. So you were running this club for?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Seven years. And I did it because I liked to share and to study and about the million dollars, to come back to the origin of all of this. I really would like to invest those money in education about fencing, swords and all our heritage because we are a niche. You know, I don't want to be a mass argument, but people should know better about their past and their about their history by touching with their own hands.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. So when you've sorted out the Malleus processes and everything and it has expanded into this gigantic sword empire, you will have a spare million euros that you can spend on this project.

Eleonora Rebecchi: Yes. And surely some of this money spent in education would go for helping children and also children that are not living in a right way in a difficult situation to rise from their difficulties through fencing too. It would be amazing. It would be really amazing.

Guy Windsor: So many kids came out of bad situations through football or boxing. Or music, even. Why not through historical fencing as well?

Eleonora Rebecchi: Exactly. There are two young people I have started to approach historical fencing without being a case. They find historical fencing, but they don’t know it exists many times.

Guy Windsor: Yeah. And if more people knew we existed, then that would definitely be better. Brilliant. Well, thank you so much for joining me today, Eleonora, it has been lovely catching up with you.

Eleonora Rebecchi: For me too. It was amazing to meet you and to share a chat together.